During Digestion The Major Site Of Nutrient Absorption Is The

Imagine food as a complex package, a treasure chest of energy and essential building blocks our bodies desperately need. But this treasure remains locked until digestion, a sophisticated process that breaks down food into usable components. The crucial stage where these liberated nutrients finally cross into our bloodstream is a carefully orchestrated event, primarily occurring in one specific location, a hub of absorption and vital to our survival.

This article delves into the primary site of nutrient absorption during digestion – the small intestine. We’ll examine its unique structure, the key processes that facilitate absorption, and explore the implications of impaired absorption for overall health. We will also consider ongoing research aimed at improving nutrient uptake and addressing absorption-related disorders. Understanding this critical area of our digestive system is fundamental to comprehending how we derive sustenance from food and maintain well-being.

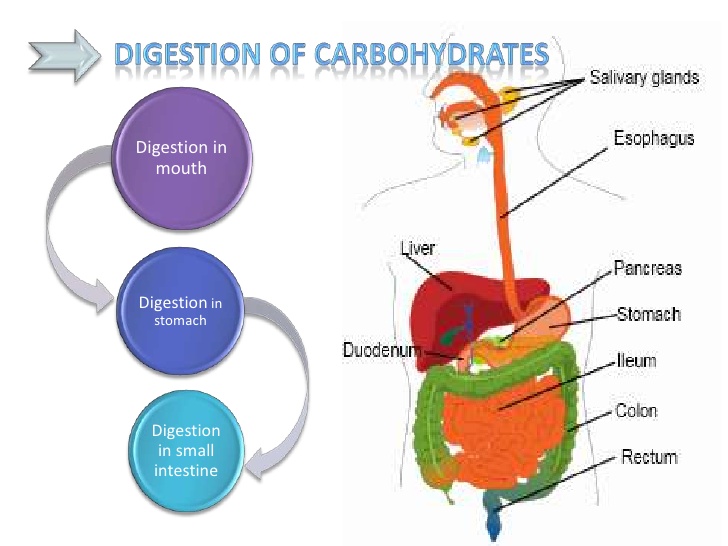

The Small Intestine: A Marvel of Surface Area

The small intestine is a long, coiled tube extending from the stomach to the large intestine. Contrary to its name, its importance in nutrient absorption is immense.

Its primary function is to absorb the majority of nutrients from digested food. This absorption is facilitated by its specialized structure, designed to maximize surface area.

Structural Adaptations for Maximum Absorption

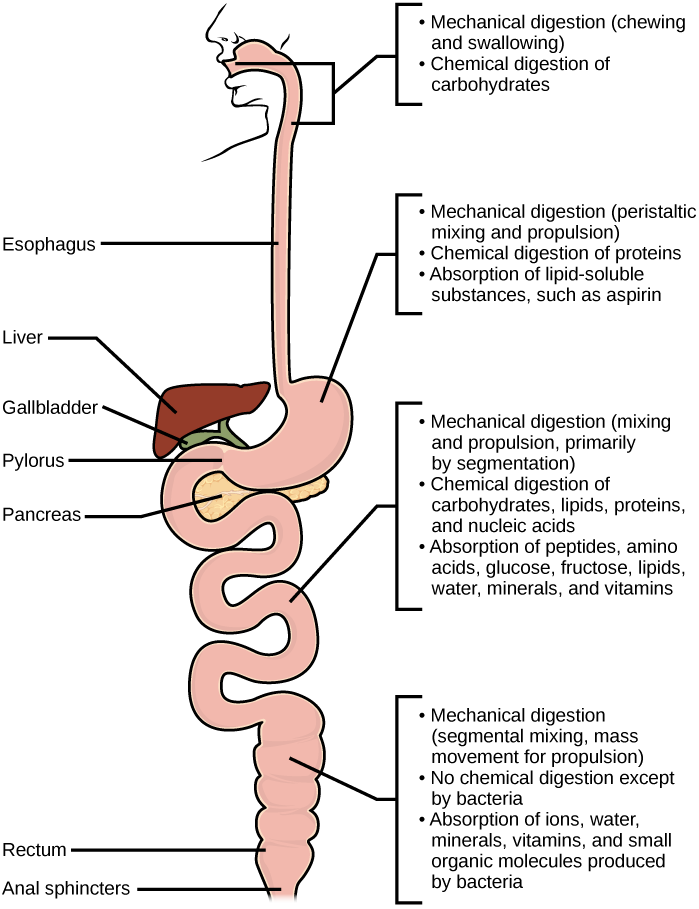

The small intestine’s effectiveness relies on three key features that dramatically increase its surface area. These features include circular folds, villi, and microvilli.

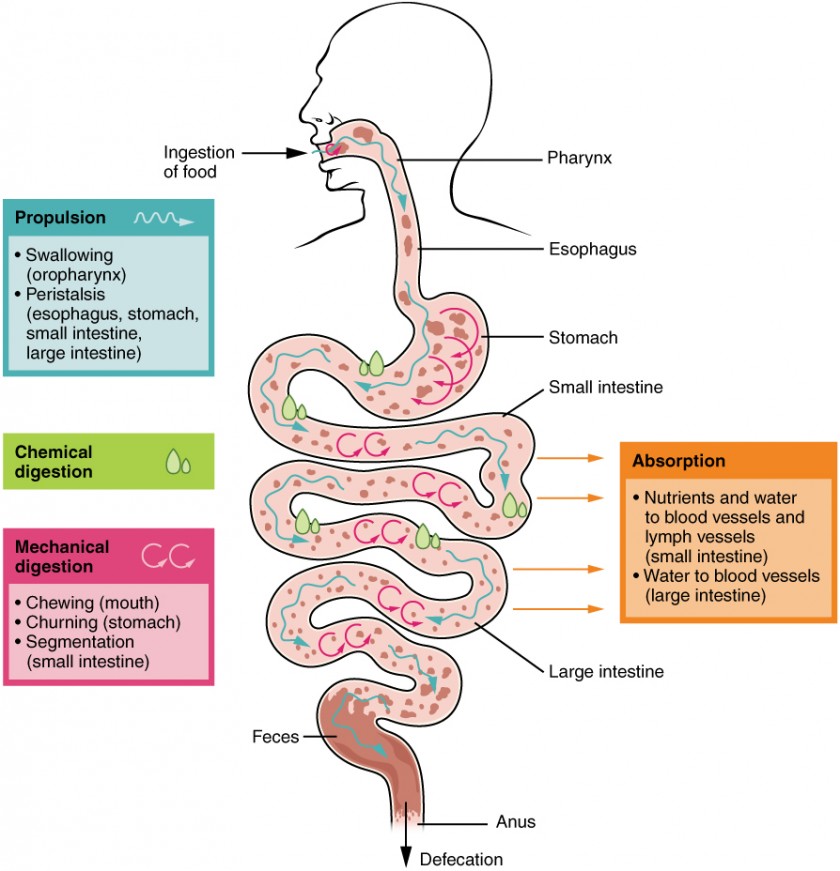

Circular folds are large ridges in the lining of the small intestine that force chyme (partially digested food) to spiral, slowing its passage and increasing contact with the intestinal wall. This spiral motion enhances nutrient absorption.

Villi are small, finger-like projections that cover the surface of the circular folds. Each villus contains a network of capillaries and a lymphatic vessel called a lacteal, enabling efficient absorption of nutrients into the bloodstream and lymphatic system.

Microvilli are tiny, hair-like projections on the surface of the villi cells, further increasing the surface area for absorption. The microvilli create a "brush border" that contains enzymes which complete the final stages of carbohydrate and protein digestion.

The Absorption Process: A Symphony of Mechanisms

Nutrient absorption in the small intestine is not a passive process. It relies on a variety of mechanisms to transport different nutrients across the intestinal lining.

These mechanisms include simple diffusion, facilitated diffusion, active transport, and endocytosis. Each nutrient utilizes one or more of these processes to enter the bloodstream.

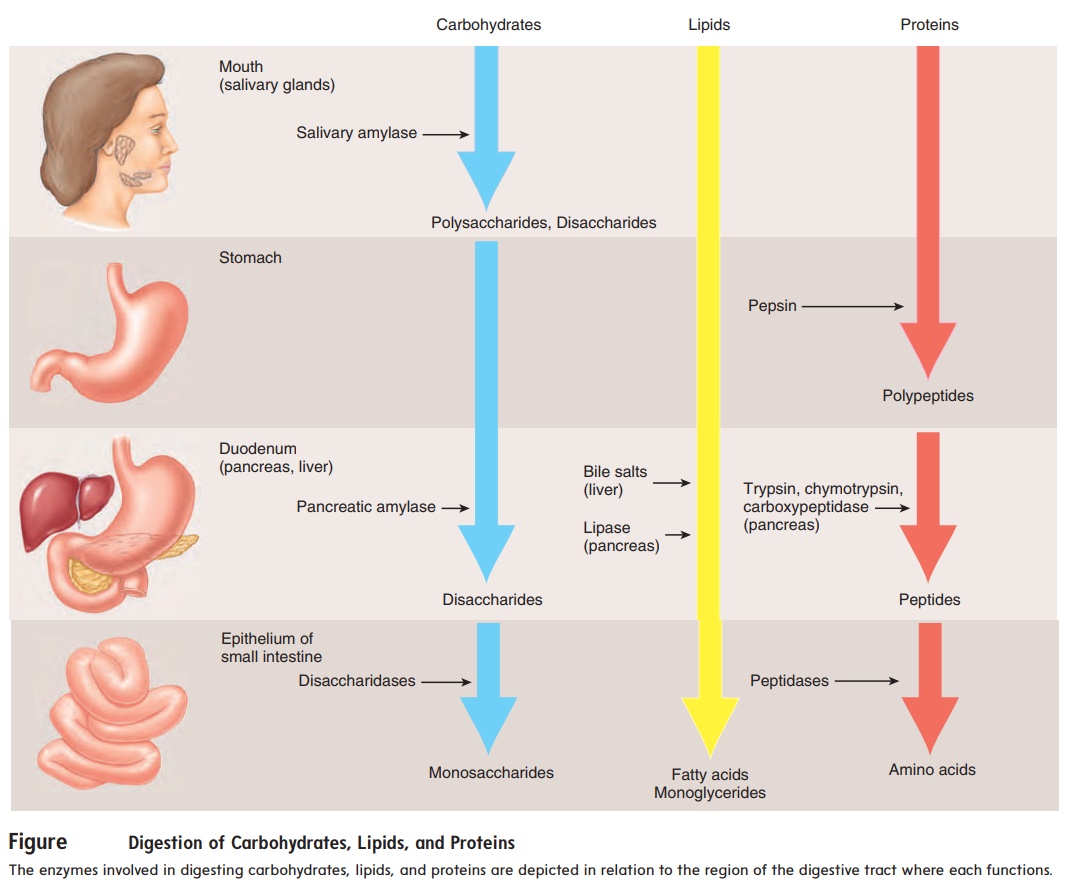

Specific Nutrient Absorption Pathways

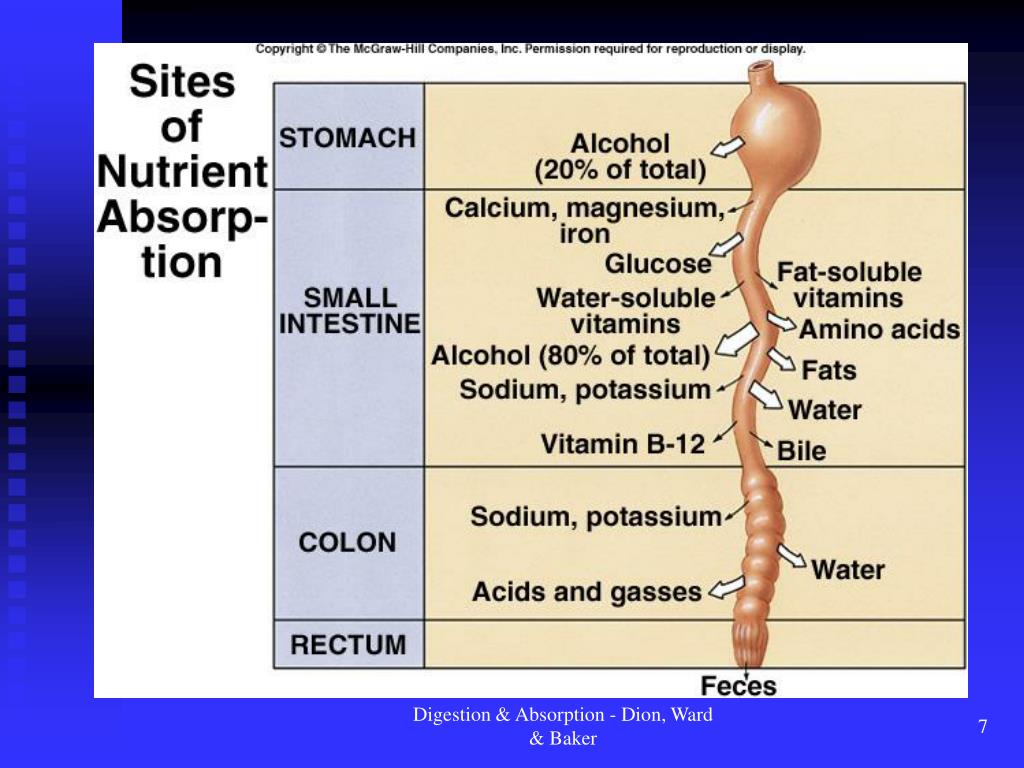

Different nutrients are absorbed through different mechanisms within the small intestine.

For example, fats are emulsified by bile and then absorbed as fatty acids and monoglycerides. These are then reassembled into triglycerides and transported via chylomicrons (lipoprotein particles) into the lacteals.

Sugars, broken down from carbohydrates, are absorbed through active transport and facilitated diffusion. Amino acids, derived from proteins, are also absorbed through active transport mechanisms.

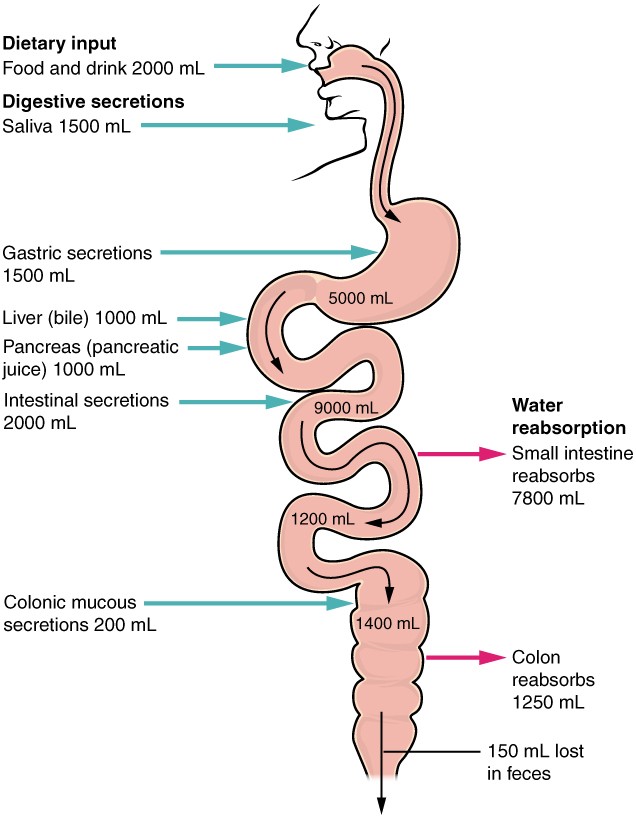

Water and electrolytes are absorbed via osmosis and diffusion, following concentration gradients. Vitamins are absorbed through various mechanisms, including active transport and diffusion, often requiring specific transport proteins.

Disruptions and Disorders: When Absorption Fails

Impaired nutrient absorption, also known as malabsorption, can lead to various health problems. These range from nutritional deficiencies to more serious conditions.

Several factors can disrupt the normal absorption process. These include diseases of the small intestine, such as celiac disease and Crohn's disease, as well as surgical removal of portions of the intestine.

Consequences of Malabsorption

Malabsorption can manifest in a variety of symptoms. These symptoms include diarrhea, bloating, weight loss, and fatigue.

Long-term malabsorption can lead to deficiencies in essential vitamins and minerals. This leads to anemia, osteoporosis, and other health problems.

Celiac disease, for example, damages the villi of the small intestine, reducing the surface area available for absorption. This is triggered by gluten, a protein found in wheat, barley, and rye.

The Future of Absorption Research

Research continues to advance our understanding of nutrient absorption. These advancements could pave the way for new therapies to treat malabsorption disorders.

Current research focuses on developing new ways to enhance nutrient absorption in individuals with compromised intestinal function. These may include novel drug delivery systems and dietary interventions.

Researchers are also exploring the role of the gut microbiome in nutrient absorption. The gut microbiome contains the bacteria, fungi, protozoa and viruses that live in your intestines.

"Understanding the complex interplay between the gut microbiome and nutrient absorption is crucial for developing personalized nutritional strategies,"notes Dr. Anya Sharma, a leading researcher in gastrointestinal physiology at the National Institutes of Health.

The small intestine, with its intricate structure and efficient absorption mechanisms, stands as a testament to the body's remarkable ability to extract sustenance from food. Further research promises to unlock even more secrets of this vital organ and improve the lives of those affected by malabsorption disorders.