How Much Cooler Should Ac Air Be

The question of optimal air conditioning temperature is sparking debate as energy costs rise and concerns about environmental impact intensify. While individual comfort remains a priority, experts are increasingly urging a re-evaluation of cooling practices to balance personal preferences with energy efficiency and public health considerations.

At the heart of the discussion is the trade-off between comfort, cost, and carbon footprint. This article examines the scientific recommendations, economic realities, and emerging technologies shaping the future of air conditioning, exploring how much cooler our indoor spaces *really* need to be.

The Science of Comfort and Efficiency

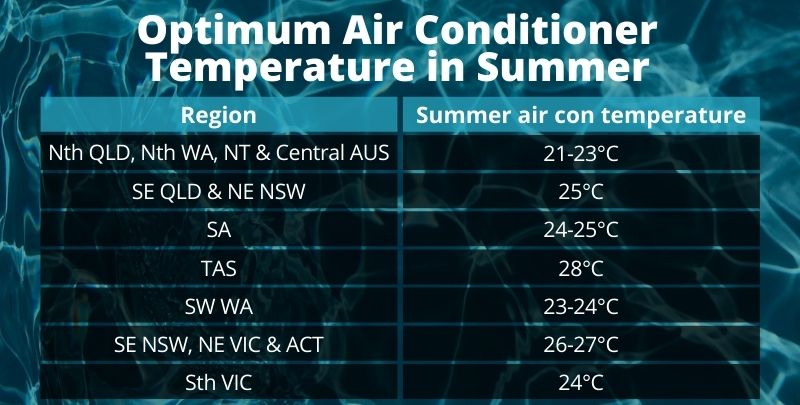

Organizations like the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) provide guidelines for acceptable indoor temperatures. Their standards often recommend a range of 73°F to 79°F (23°C to 26°C) for optimal comfort and energy efficiency.

These recommendations take into account factors such as activity level, clothing, and humidity. Deviating significantly from this range can lead to increased energy consumption without substantial improvements in perceived comfort.

“There's a sweet spot,” explains Dr. Emily Carter, an environmental scientist at the University of California, Berkeley. “Cranking the AC down to the low 60s isn't just wasteful; it can actually make you feel colder and less comfortable due to the rapid temperature change.”

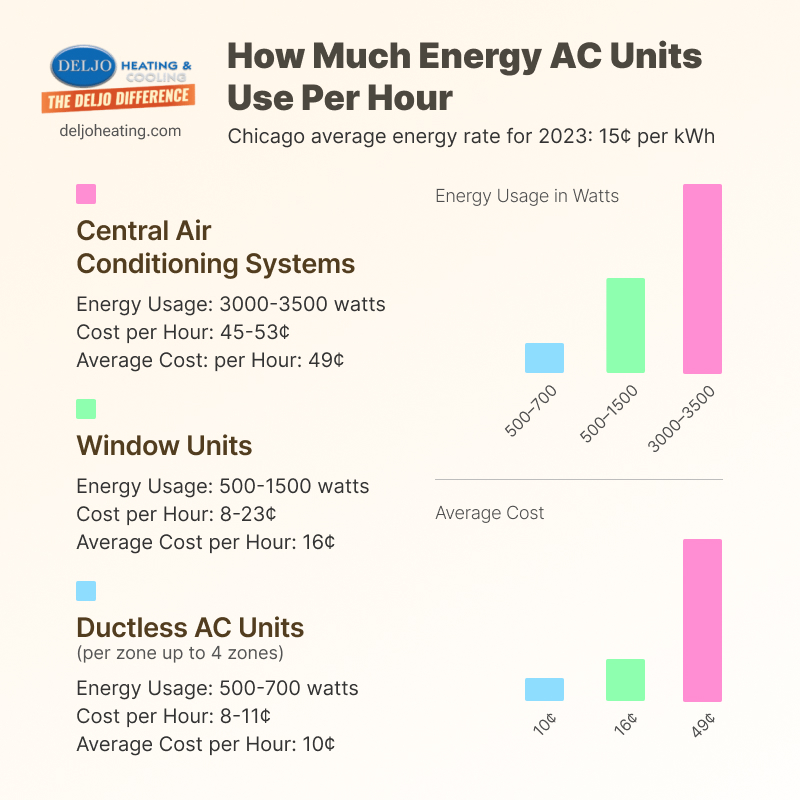

The Economic Realities of Cooling

Energy costs associated with air conditioning can be substantial, particularly during peak summer months. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), air conditioning accounts for a significant portion of household energy consumption in many regions.

Reducing AC usage, even by a few degrees, can translate into significant savings on energy bills. A study by the EIA found that raising the thermostat by just one degree can reduce cooling costs by 1-3%.

For low-income households, these savings can be particularly impactful. Programs promoting energy efficiency and offering financial assistance for upgrades can help alleviate the burden of high cooling costs.

The Environmental Impact

The environmental impact of air conditioning extends beyond energy consumption. Many refrigerants used in AC systems are potent greenhouse gases, contributing to global warming. The phasing out of older refrigerants and the development of more environmentally friendly alternatives are crucial steps in mitigating this impact.

Furthermore, the electricity used to power air conditioners often comes from fossil fuels, further exacerbating climate change. Transitioning to renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind power, is essential for decarbonizing the cooling sector.

"We need to rethink our approach to cooling," says Mark Johnson, a policy analyst at the Environmental Defense Fund. "Energy efficiency, refrigerant management, and renewable energy are all key components of a sustainable cooling strategy."

Technological Innovations and Future Trends

Emerging technologies are offering new possibilities for more efficient and sustainable cooling. Smart thermostats, for example, can learn user preferences and automatically adjust temperatures to optimize comfort and energy savings.

Advanced building materials, such as reflective roofing and improved insulation, can reduce the need for air conditioning in the first place. Passive cooling strategies, like natural ventilation and shading, can also play a significant role.

District cooling systems, which provide chilled water to multiple buildings from a central plant, are another promising solution, particularly in urban areas. These systems can be more energy efficient and cost-effective than individual air conditioning units.

A Human Perspective

For elderly individuals or those with certain medical conditions, maintaining a comfortable indoor temperature is essential for health and well-being. Extreme heat can pose serious risks, and access to air conditioning can be a life-saving resource.

During heat waves, community centers and libraries often serve as cooling centers, providing a safe and comfortable space for vulnerable populations. Ensuring equitable access to cooling is a critical public health issue.

One resident, Maria Rodriguez, a senior citizen living in Phoenix, Arizona, relies heavily on air conditioning during the summer months. "Without it, I don't know what I would do," she says. "It's not just about comfort; it's about survival."

Conclusion

The debate over how much cooler our AC air should be is a complex one, with no easy answers. Balancing individual comfort with energy efficiency, environmental concerns, and public health considerations requires a multifaceted approach.

By adopting smarter cooling practices, embracing technological innovations, and prioritizing equitable access to cooling, we can create a more sustainable and comfortable future for all. A collective effort is needed to drive the conversation, push for more sustainable alternatives, and change people's habits when it comes to cooling.

Ultimately, the ideal AC temperature is not a fixed number but rather a dynamic balance that adapts to individual needs, local conditions, and evolving technologies.