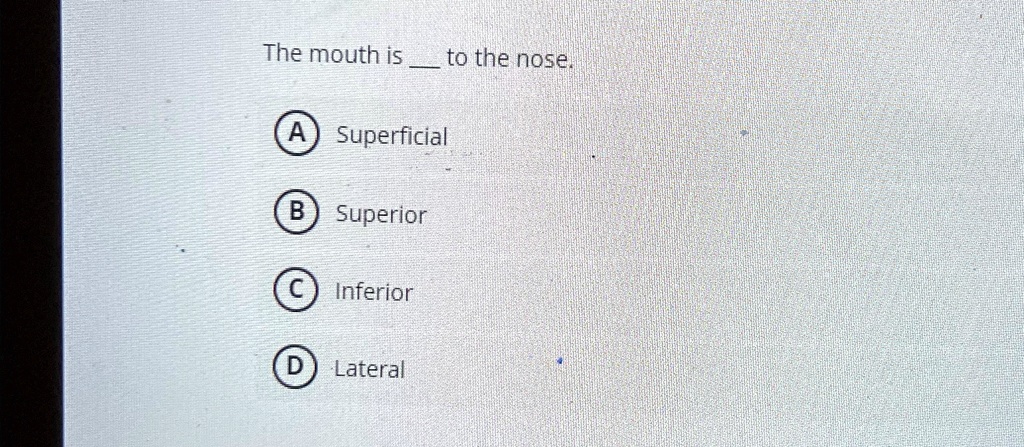

Is The Mouth Superior To The Nose

The human respiratory system, a seemingly straightforward conduit for life-sustaining air, has become the unlikely battleground for a debate that has simmered, resurfaced, and now, in the wake of a global pandemic, rages with renewed intensity: Is breathing through the mouth a viable alternative to nasal respiration, or a dangerous shortcut with potentially detrimental consequences?

What was once relegated to hushed conversations among medical professionals and late-night internet searches has now entered mainstream discourse, fueled by viral trends, anecdotal evidence, and a growing awareness of the intricate connection between breathing and overall health. The core question driving this debate is whether the physiological design favors nasal breathing, and if so, what are the implications of consistently opting for its oral counterpart?

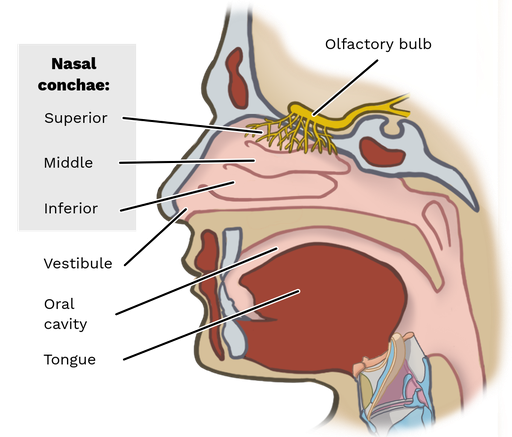

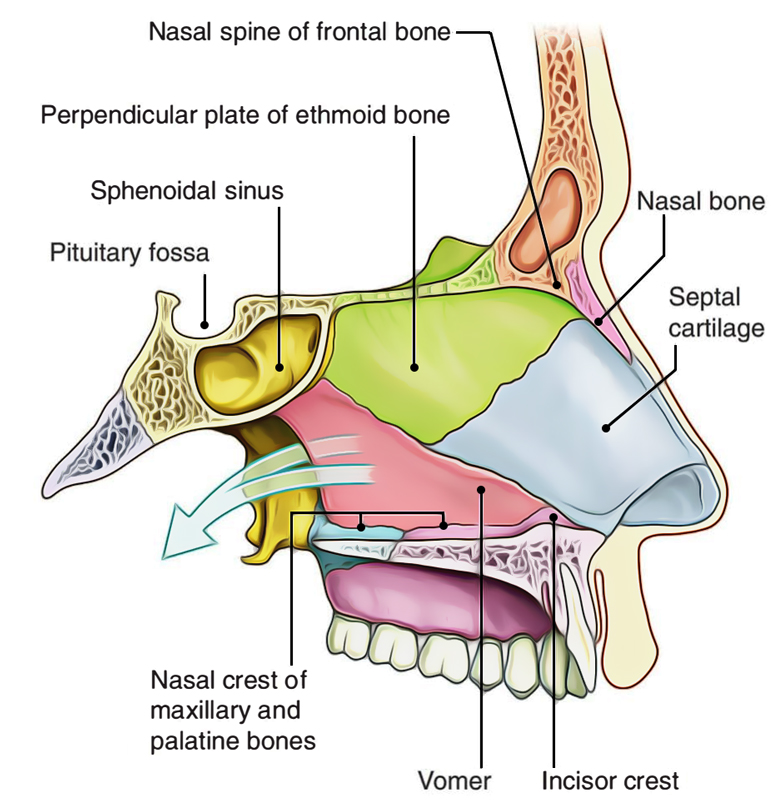

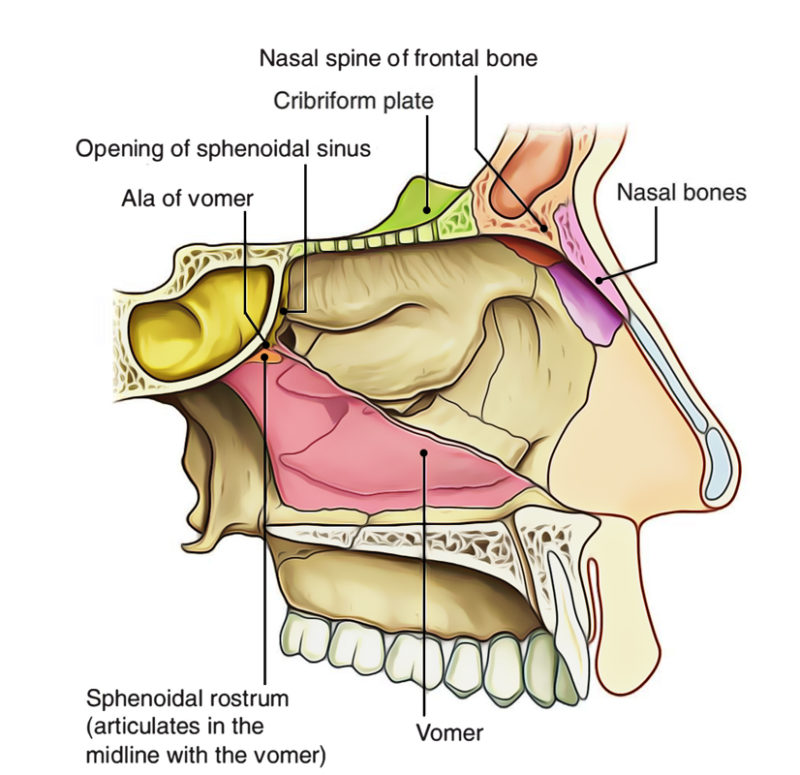

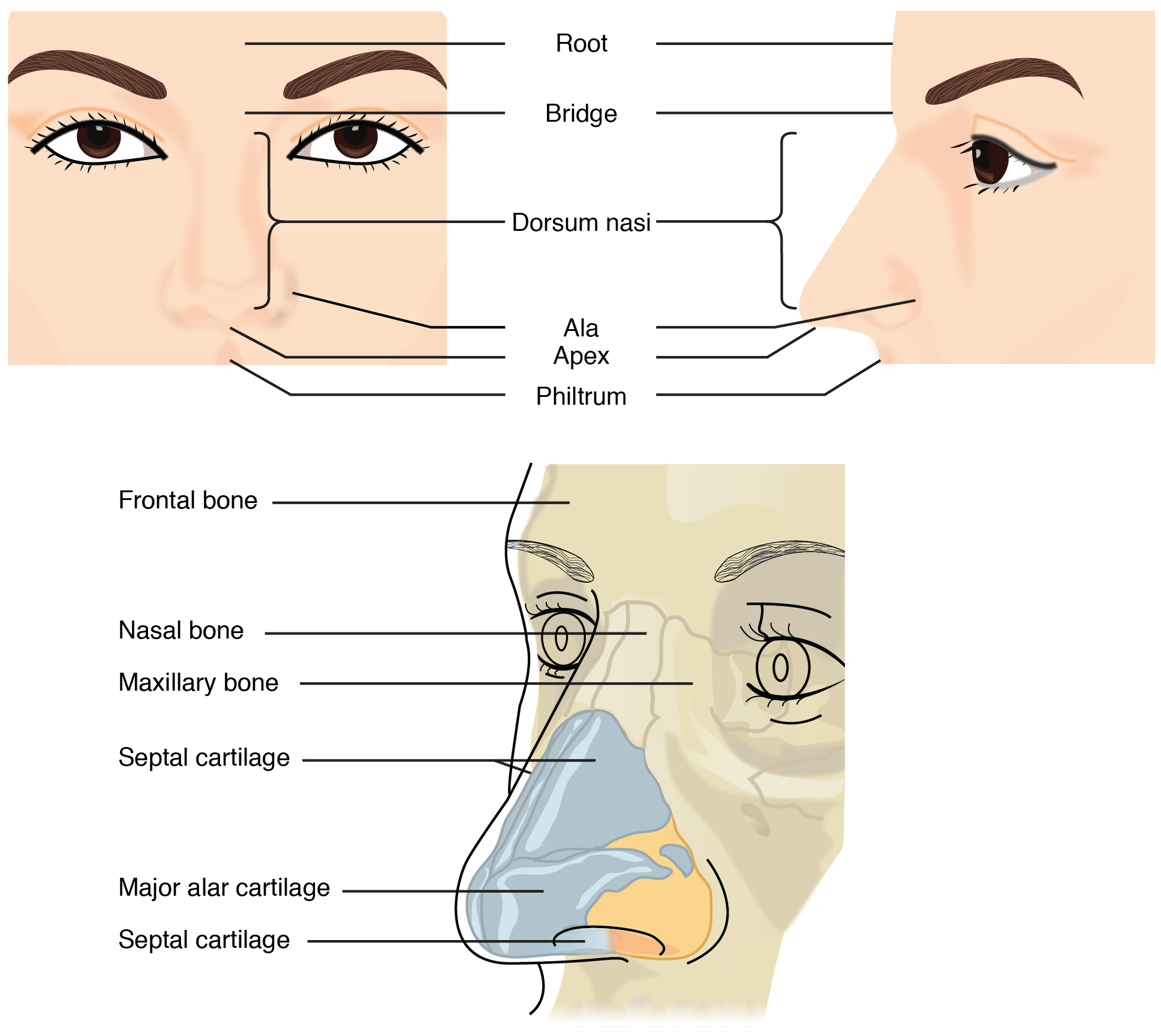

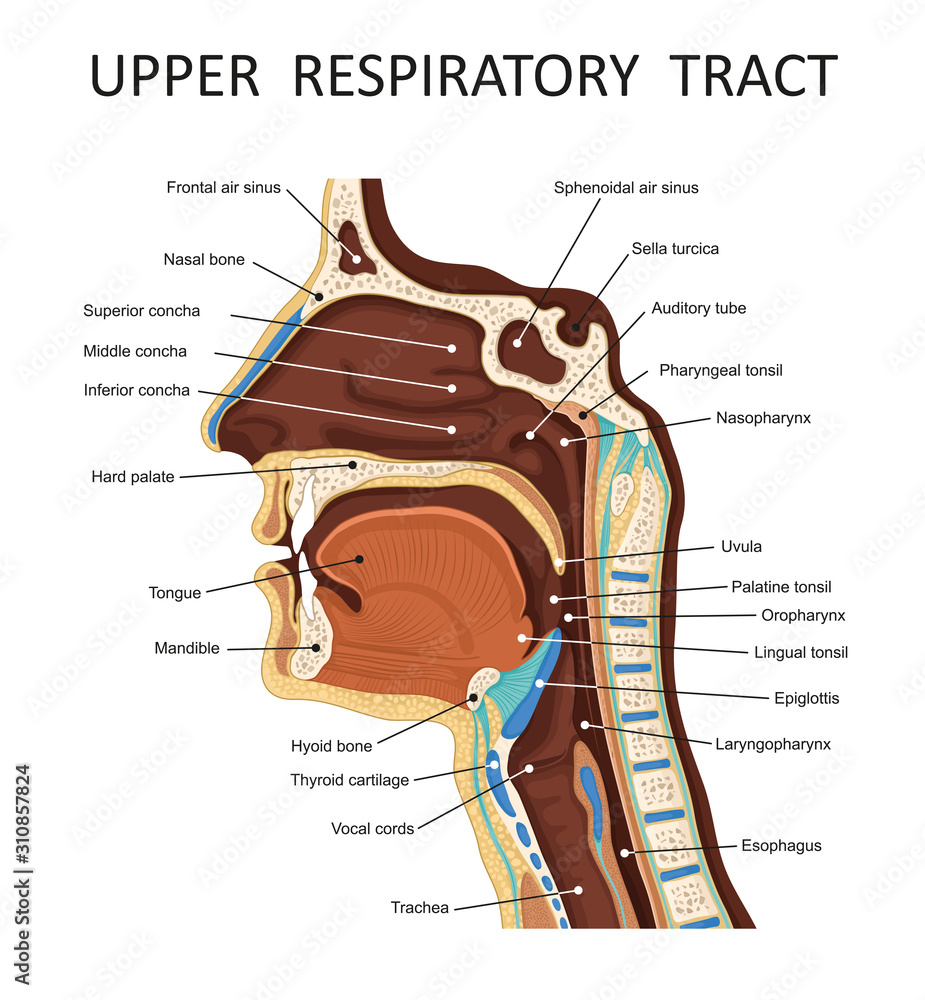

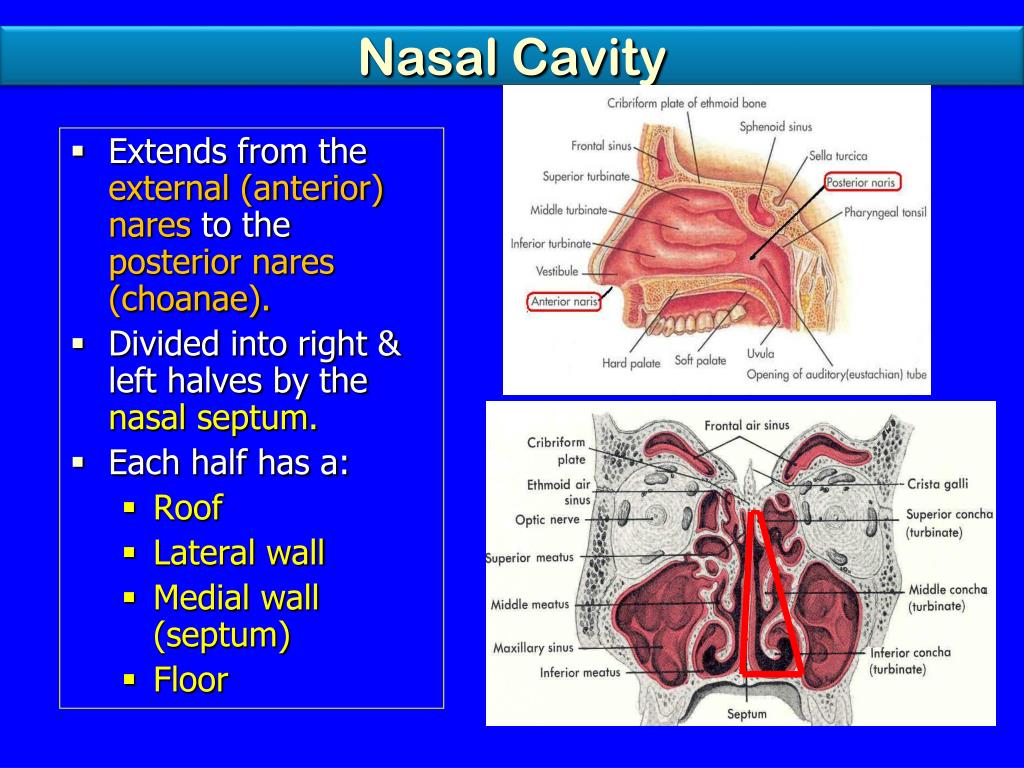

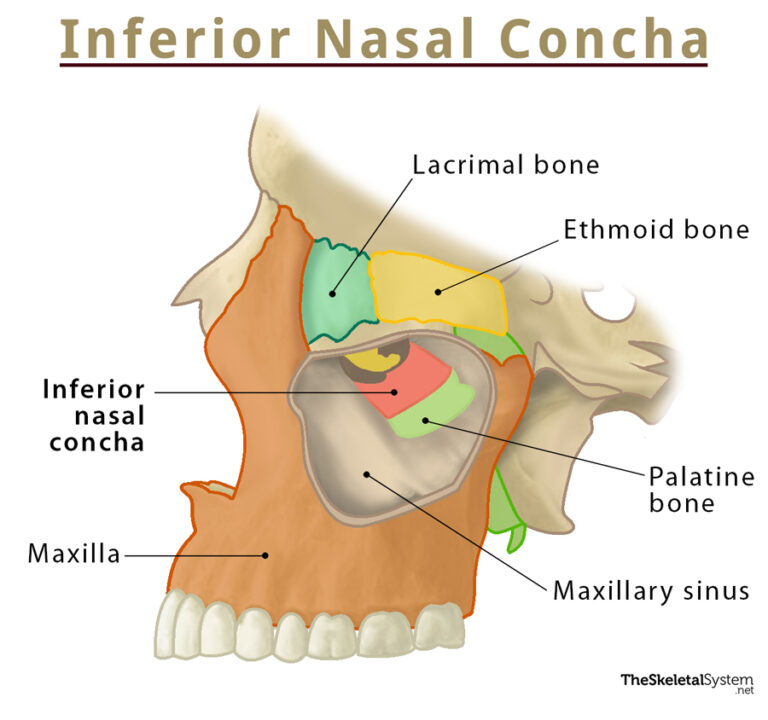

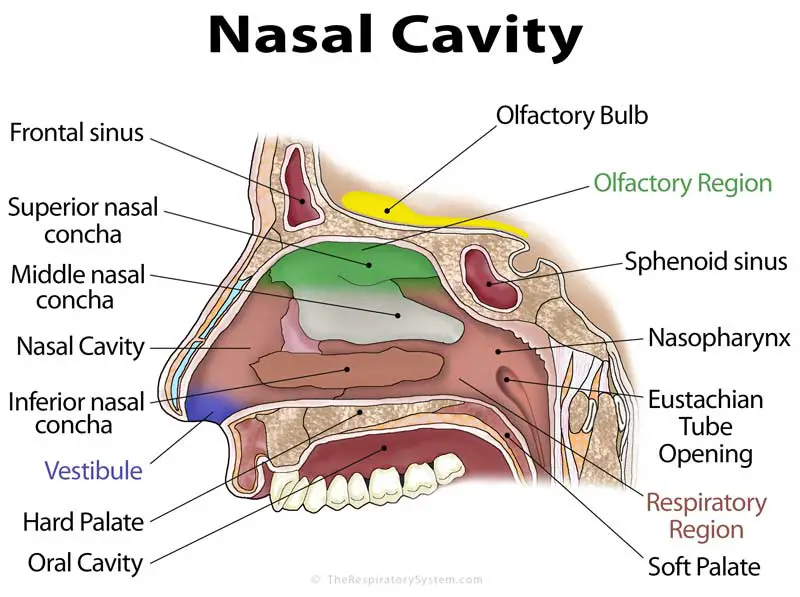

The Nose: A Natural Air Filter

The nose, with its intricate network of cilia, nasal passages, and mucous membranes, serves as the body's primary air filtration system. Dr. Neil Bhattacharyya, a professor of otolaryngology at Harvard Medical School, emphasizes this crucial role, stating that the nose "humidifies, warms, and filters the air before it reaches the lungs."

These functions are not merely incidental; they are critical for optimal respiratory health. Filtering removes particulate matter, allergens, and pathogens, reducing the risk of respiratory infections and inflammation.

Warming the air prevents damage to the delicate lung tissue, particularly in cold environments. Humidifying ensures that the air reaching the lungs doesn't dry out the airways, which can lead to irritation and impaired function.

Furthermore, the nose plays a vital role in producing nitric oxide, a molecule that improves oxygen absorption and acts as a vasodilator, improving blood flow. This has been confirmed in several studies published in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine.

The Mouth: An Emergency Backup?

While the nose is the designated primary airway, the mouth serves as a backup system. Oral breathing becomes essential during periods of intense physical exertion or nasal congestion when the demand for air exceeds the nose's capacity.

However, chronic mouth breathing bypasses the nasal filtration system, delivering unfiltered, dry, and often colder air directly to the lungs. This can lead to a cascade of negative consequences. Dr. Steven Park, author of "Sleep Interrupted," argues that "mouth breathing is essentially a pathological condition."

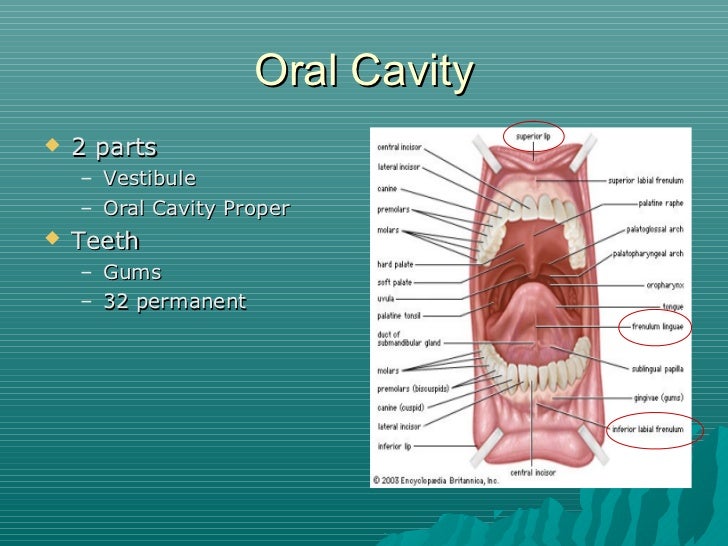

The most immediate consequence is often dry mouth, which can contribute to dental problems such as cavities, gingivitis, and bad breath. The lack of salivary lubrication also disrupts the oral microbiome, potentially promoting the growth of harmful bacteria.

The Skeletal Impact of Mouth Breathing

The long-term effects of chronic mouth breathing extend beyond the oral cavity, influencing facial development and skeletal structure, particularly in children. Studies published in the Journal of the American Dental Association suggest a link between mouth breathing and altered craniofacial growth.

Children who consistently breathe through their mouths may develop a narrow upper jaw, a high-arched palate, and a recessed chin. These structural changes can contribute to malocclusion (misaligned teeth) and an increased risk of temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders.

These changes can then affect the tongue's resting position, which plays an important part in proper swallowing patterns. This leads to other skeletal issues, and sometimes speech impediments.

The Debate: Nuance and Context

While the evidence overwhelmingly favors nasal breathing as the optimal method, the debate is not without nuance. Some argue that the detrimental effects of mouth breathing are often overstated or that certain individuals may be more susceptible to its negative consequences.

For example, individuals with chronic nasal congestion due to allergies or anatomical abnormalities may find it difficult to breathe exclusively through their noses. In these cases, the benefits of any breathing may outweigh the potential risks of mouth breathing.

Additionally, some athletic trainers advocate for mouth breathing during high-intensity exercise, arguing that it allows for greater airflow and improved performance. However, this practice should be approached with caution, as it can lead to hyperventilation and other respiratory issues.

It's also important to consider that individuals may unconsciously switch between nasal and oral breathing throughout the day, depending on their activity level, posture, and stress levels. The key is to identify and address any underlying causes of chronic mouth breathing and to prioritize nasal breathing whenever possible.

Looking Ahead: Promoting Nasal Breathing

The growing awareness of the importance of nasal breathing has led to the development of various strategies and interventions to promote its practice. These include nasal strips and dilators to improve airflow, myofunctional therapy to strengthen oral and facial muscles, and exercises to improve breathing patterns.

Furthermore, addressing underlying conditions such as allergies, sinusitis, and sleep apnea can help alleviate nasal congestion and encourage nasal breathing. Early intervention in children is particularly important to prevent or mitigate the potential long-term effects of mouth breathing.

Ultimately, the "mouth versus nose" debate underscores the profound connection between breathing and overall health. While occasional mouth breathing is unlikely to cause significant harm, prioritizing nasal respiration and addressing any underlying breathing issues is crucial for optimizing respiratory function, craniofacial development, and overall well-being. Continuing research and increased awareness will be key in guiding individuals towards healthier breathing habits.