Research On Memory Construction Indicates That

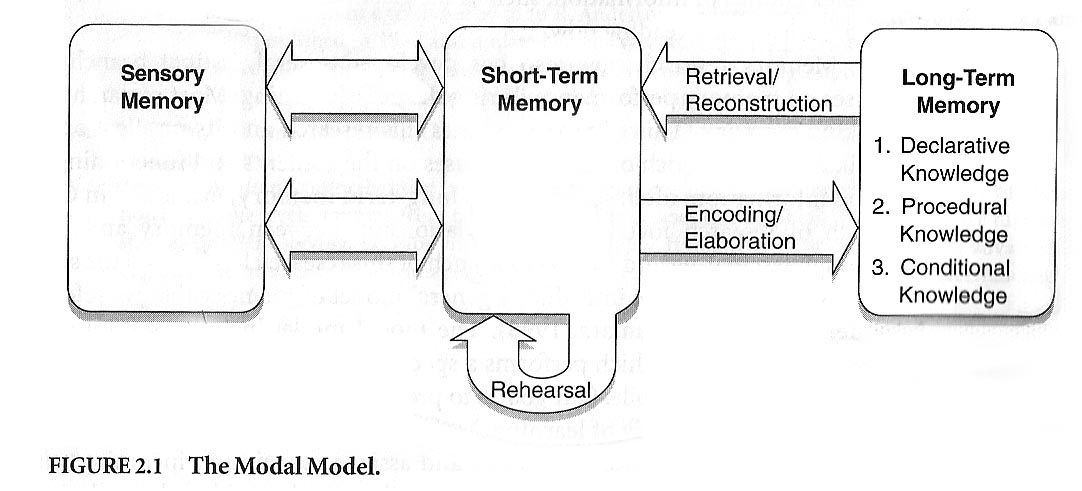

The human memory, long considered a reliable record of past experiences, is increasingly understood as a malleable and reconstructive process. Recent research is painting a picture of memory not as a video recording, but as a constantly evolving narrative, subject to distortion and influence. These findings have profound implications for fields ranging from eyewitness testimony to personal identity.

At the heart of this developing understanding lies the recognition that memories are not static entities stored in a single location in the brain. Instead, they are actively reconstructed each time they are recalled, making them susceptible to alteration. This article will delve into the latest research illuminating the constructive nature of memory, exploring its mechanisms, its implications, and its potential for both benefit and harm. It will examine the scientific basis for this view, drawing on studies from neuroscience, psychology, and related fields. It will also address the ethical and practical consequences of accepting that our memories may not be entirely accurate reflections of reality.

The Neuroscience of Reconstruction

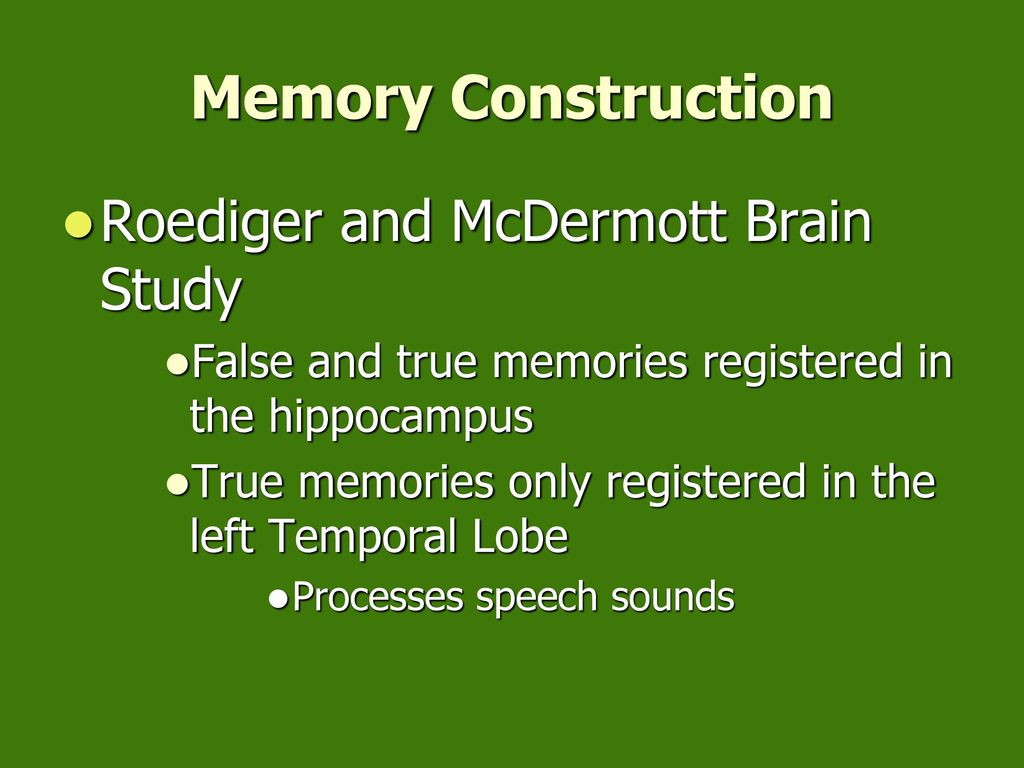

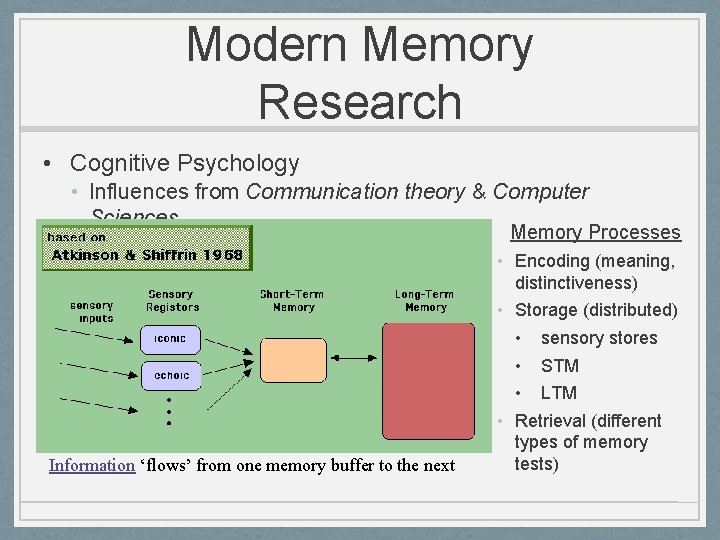

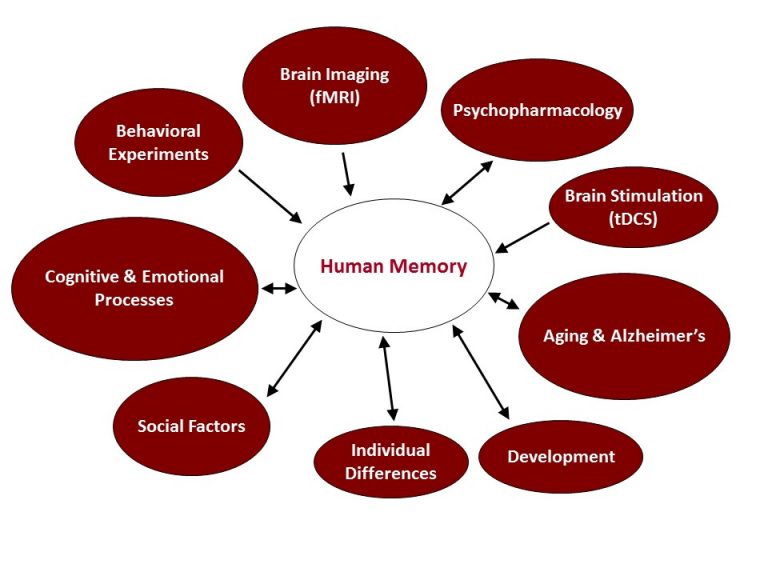

Neuroscience research has been pivotal in demonstrating the reconstructive nature of memory. Studies utilizing brain imaging techniques like fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) have shown that recalling a memory activates a network of brain regions, not just a single area.

These regions include the hippocampus, crucial for encoding new memories, and the prefrontal cortex, involved in higher-level cognitive functions such as decision-making and self-awareness. The involvement of these areas during recall suggests that memory retrieval is an active process of assembling information fragments rather than simply replaying a stored file.

Furthermore, research on synaptic plasticity, the ability of synapses (connections between neurons) to strengthen or weaken over time, provides a biological mechanism for memory modification. Each time a memory is recalled, the synaptic connections associated with that memory are potentially altered, leading to changes in the memory's content or emotional associations.

Psychological Studies and Memory Distortions

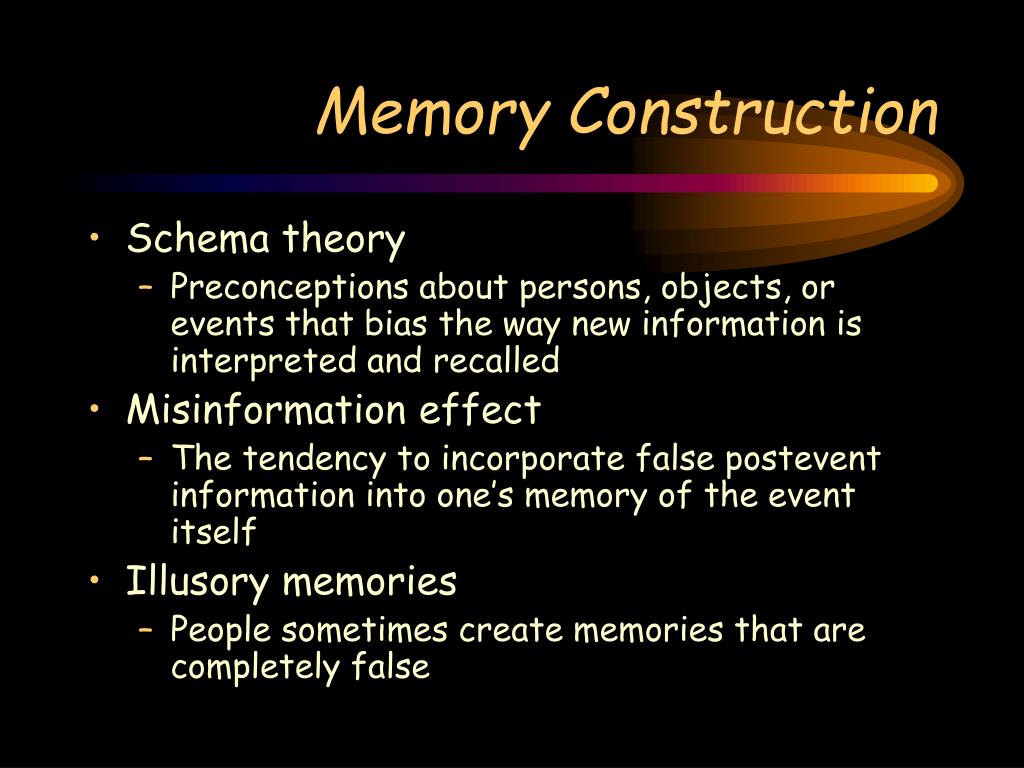

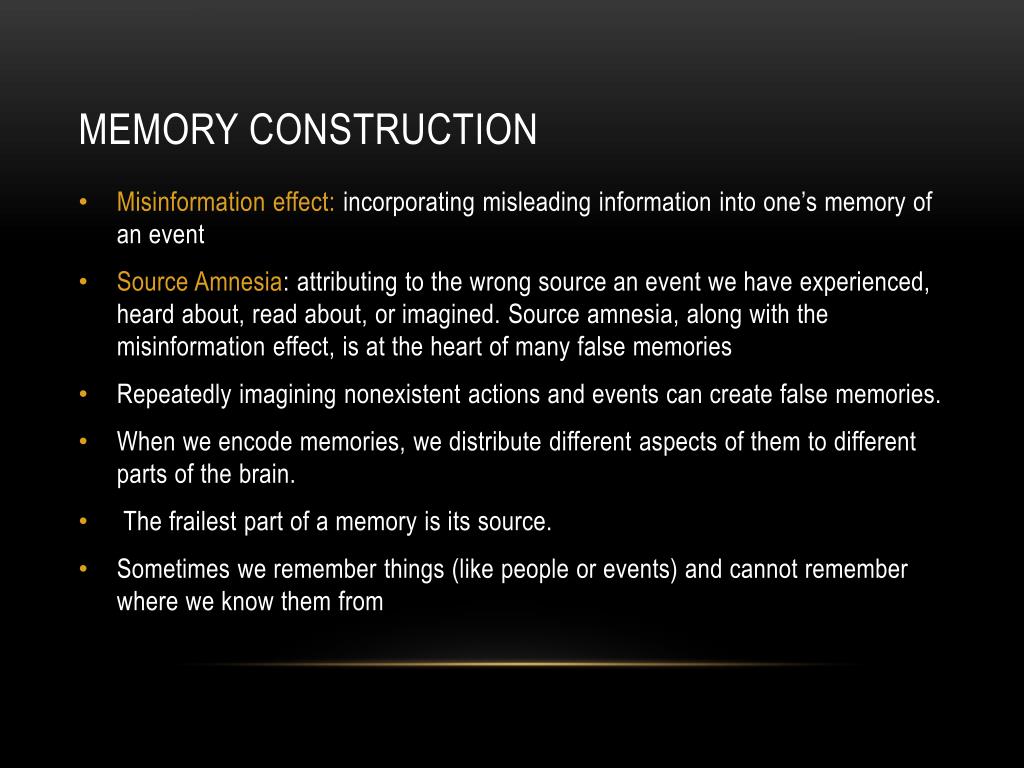

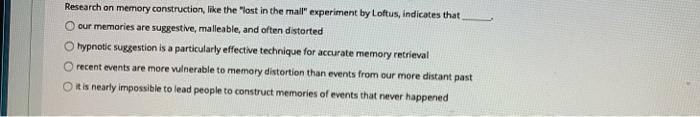

Psychological experiments have long demonstrated the fallibility of memory and its susceptibility to distortion. The famous Elizabeth Loftus's work on the misinformation effect showed that exposure to misleading information after an event can alter a person's memory of that event.

In her classic study, participants who watched a video of a car accident were later asked questions that contained subtly misleading information, such as using the word "smashed" instead of "hit" to describe the collision. Those exposed to the misleading information were more likely to report seeing broken glass at the scene, even though there was no broken glass in the video. This highlights how easily memories can be influenced by external suggestions.

Other research has explored the phenomenon of false memories, in which individuals recall events that never actually happened. These false memories can be surprisingly vivid and emotionally charged, making it difficult for individuals to distinguish them from genuine memories. Techniques like the Deese-Roediger-McDermott (DRM) paradigm have been used to reliably induce false memories in laboratory settings.

Implications for Eyewitness Testimony

The understanding that memory is reconstructive has profound implications for the criminal justice system, particularly regarding eyewitness testimony. Eyewitness accounts are often considered compelling evidence, but research shows they are prone to error and distortion.

Factors such as stress, leading questions, and post-event information can significantly influence an eyewitness's memory of a crime. Recognizing this fallibility has led to reforms in police procedures, such as the implementation of blind lineups and the use of cognitive interviewing techniques to minimize suggestion and maximize accurate recall.

The Innocence Project, an organization dedicated to exonerating wrongly convicted individuals through DNA testing, has found that mistaken eyewitness identification is a contributing factor in a significant percentage of wrongful convictions. This underscores the importance of critically evaluating eyewitness testimony and considering other forms of evidence.

Memory and Personal Identity

The reconstructive nature of memory also raises questions about the relationship between memory and personal identity. If our memories are constantly being revised and reshaped, what does that say about our sense of self?

Some argue that memory is crucial for maintaining a coherent sense of identity over time. Our memories provide a narrative framework for understanding who we are, where we came from, and what we value. However, others argue that an overreliance on memory can be limiting, and that our identities are more fluid and adaptable than our memories might suggest.

Furthermore, the phenomenon of repressed memories, controversial within the field of psychology, raises complex questions about the reliability of memories that have been seemingly forgotten and then later recovered. The debate continues about the authenticity and validity of recovered memories of trauma.

The Future of Memory Research

Research on memory construction is an ongoing and evolving field. Future research is likely to focus on developing more sophisticated techniques for understanding the neural mechanisms underlying memory reconstruction. This includes using advanced brain imaging techniques to track the dynamic changes that occur in the brain during memory retrieval and reconsolidation.

Another important area of research is exploring the potential for using this knowledge to improve memory function. For example, researchers are investigating ways to enhance memory accuracy and reduce the likelihood of false memories. This research has the potential to benefit individuals with memory disorders as well as the general population.

Ultimately, understanding the constructive nature of memory is not about discrediting memory altogether, but about appreciating its complexity and its potential for both accuracy and error. By acknowledging the fallibility of memory, we can develop strategies for mitigating its biases and using it more effectively to learn from the past and navigate the future.

+Does+research+in+memory+construction.jpg)