Dna Analysis Reveals Troubling News About Shrunken Heads

Imagine a hushed laboratory, the air thick with anticipation. Sunlight streams through the window, illuminating a team of scientists huddled around a computer screen. They're examining intricate DNA sequences, each line a potential clue to a centuries-old mystery: the origins of shrunken heads, or tsantsa.

New DNA analysis is revealing that the story behind these artifacts, once thought to be solely the product of specific Indigenous groups in the Amazon, is far more complex, and potentially troubling, than previously understood. This research suggests a history intertwined with colonialism, trade, and the dark reality of exploitation, challenging romanticized notions of isolated cultural practices.

The Legacy of the Tsantsa

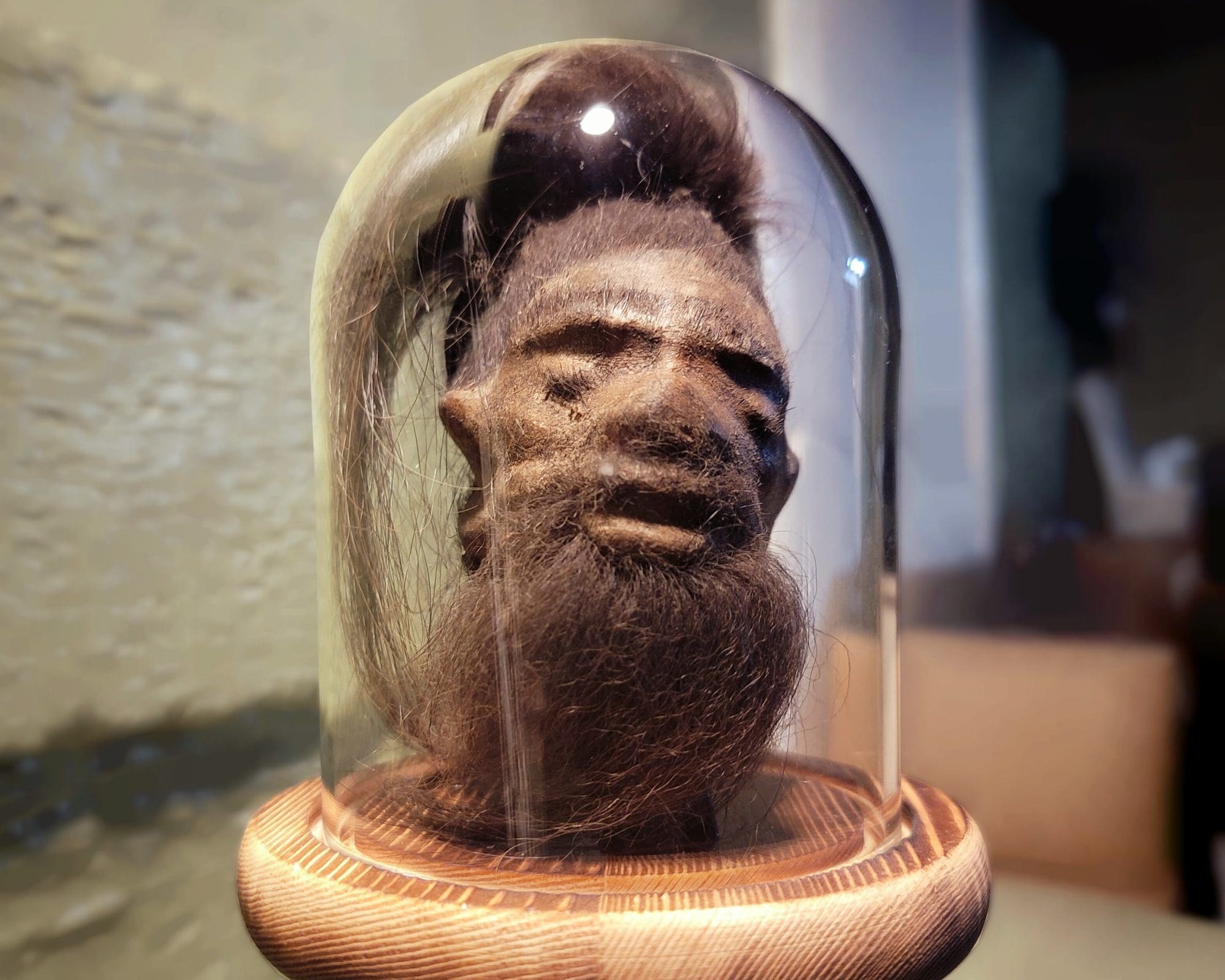

For generations, the practice of shrinking heads has been associated with the Shuar, Achuar, Huambisa, and Awajún peoples of Ecuador and Peru. These Indigenous groups traditionally created tsantsa as part of complex spiritual rituals. The process involved carefully removing the skull, boiling the skin, and preserving it with hot stones and sand, resulting in a miniature version of the deceased's head.

According to Dr. Alice Roberts, an anthropologist specializing in South American cultures, the creation of tsantsa was deeply rooted in beliefs about power and the soul. "The taking and shrinking of a head was not merely an act of violence, but a ritual intended to capture the spirit of the deceased, preventing them from seeking revenge," she explains in a recent interview.

Beyond Ritual: A Darker Truth

However, the allure of the macabre soon caught the attention of Western collectors and traders. The demand for tsantsa in the late 19th and early 20th centuries fueled a brutal trade, prompting some Indigenous groups to shrink the heads of enemies or even victims killed solely for this purpose. This commercialization distorted the original spiritual significance, creating a market driven by greed and exploitation.

The recent DNA analysis, conducted by a team at the Smithsonian Institution, examined the genetic material extracted from a collection of tsantsa held in various museums worldwide. The findings are shedding light on the true origins of these artifacts, revealing a pattern that deviates significantly from the previously accepted narrative.

Initial reports indicate that a substantial percentage of the tsantsa analyzed do not originate from the Shuar or related groups. Some show genetic markers consistent with individuals from entirely different regions, suggesting they may have been obtained through trade or, more disturbingly, through violent means.

Implications for Museums and Repatriation

These discoveries have significant implications for museums holding collections of tsantsa. The findings raise ethical questions about the provenance of these artifacts and the responsibility of institutions to repatriate them to their rightful communities. "It is crucial for museums to engage in open and transparent dialogue with Indigenous groups to determine the appropriate course of action," says Dr. Ken Hale, a repatriation specialist working with several museums.

The implications go beyond just the physical return of objects. Repatriation also involves acknowledging the history of exploitation and violence associated with the trade in tsantsa and working to restore dignity to the affected communities. It's about healing historical wounds and fostering a deeper understanding of cultural heritage.

The revelations from this DNA analysis serve as a stark reminder that the story of the tsantsa is not simply a tale of exotic rituals. It is a complex and often unsettling narrative that reflects the impact of colonialism, the allure of the macabre, and the enduring need for ethical considerations in the study and preservation of cultural artifacts.

As research continues and more tsantsa are analyzed, we can expect further insights into this dark chapter of history. Hopefully, these discoveries will contribute to a more honest and respectful understanding of the past, one that honors the voices and experiences of the Indigenous communities whose heritage has been so profoundly affected.