Which Of The Following Is Not A Phagocytic Cell

The human body, a complex and intricate network of cells and systems, relies heavily on the immune system to defend against a constant barrage of pathogens and foreign invaders. Within this system, specialized cells known as phagocytes play a crucial role, acting as the body's "clean-up crew" by engulfing and digesting harmful substances.

However, not every cell in the immune system is equipped with this phagocytic capability. This article will delve into the world of immune cells, clarifying which of the common immune cells does *not* possess the ability to perform phagocytosis, a key process in maintaining our health.

Understanding the diverse roles of immune cells is fundamental to comprehending how our bodies combat infections and diseases. This knowledge is crucial not only for healthcare professionals but also for anyone interested in gaining a deeper appreciation of their own immune system.

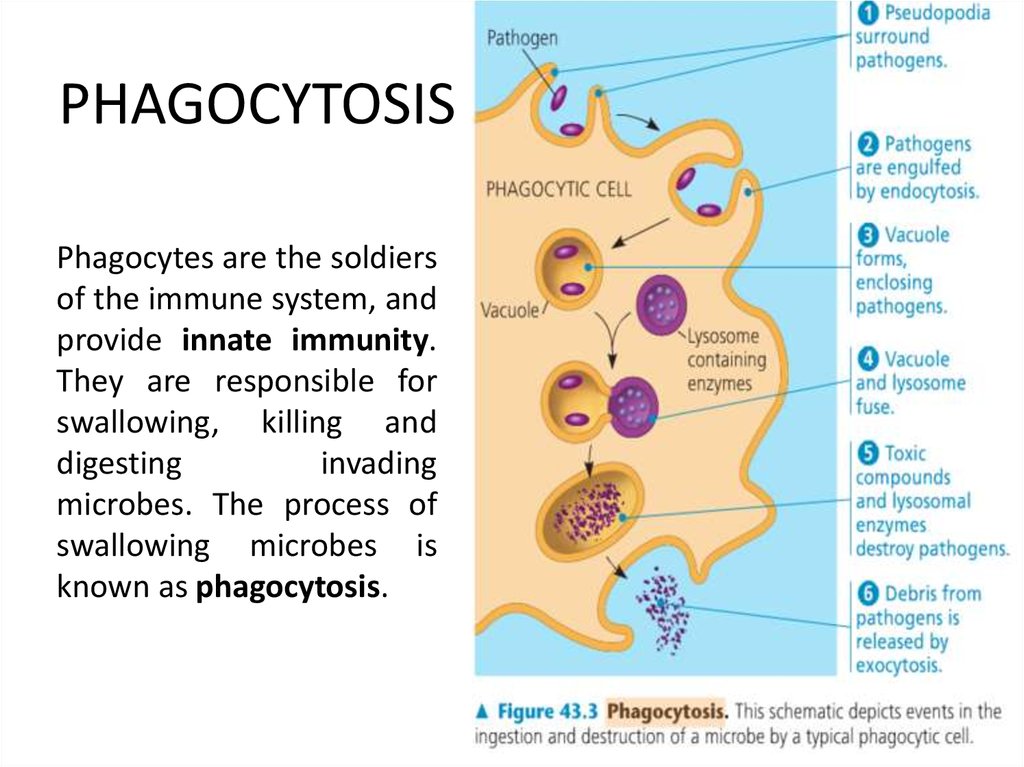

Phagocytosis: The Body's Internal Scavengers

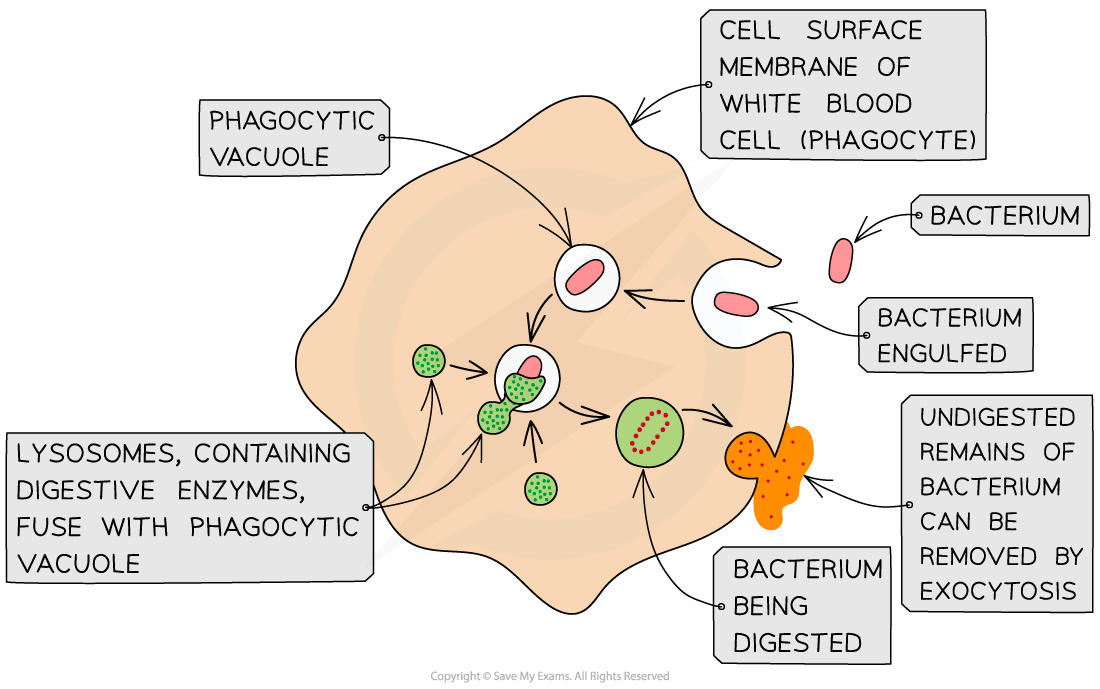

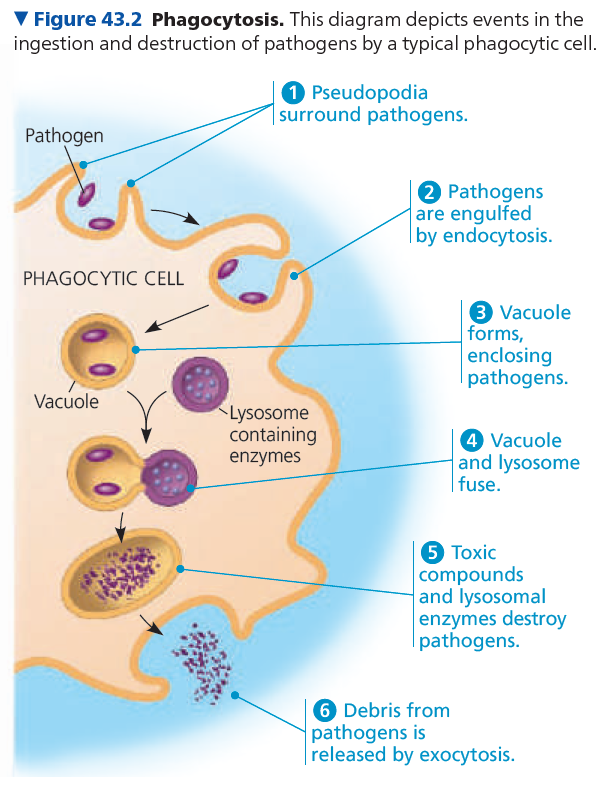

Phagocytosis, derived from the Greek words "phagein" (to eat) and "kytos" (cell), is the process by which certain cells engulf and digest other cells, debris, and foreign particles. This process is essential for clearing infections, removing dead or damaged cells, and initiating the adaptive immune response.

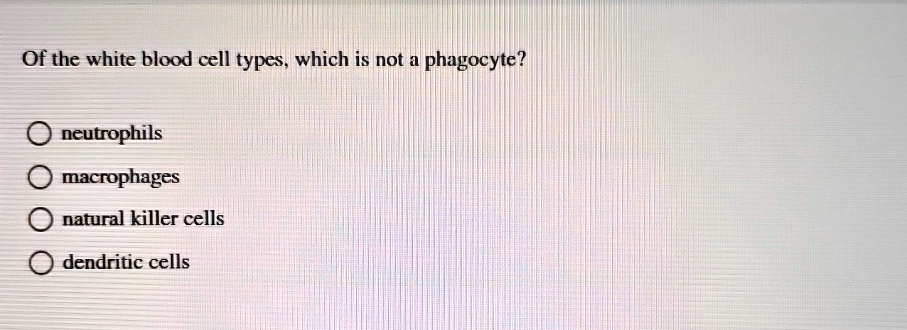

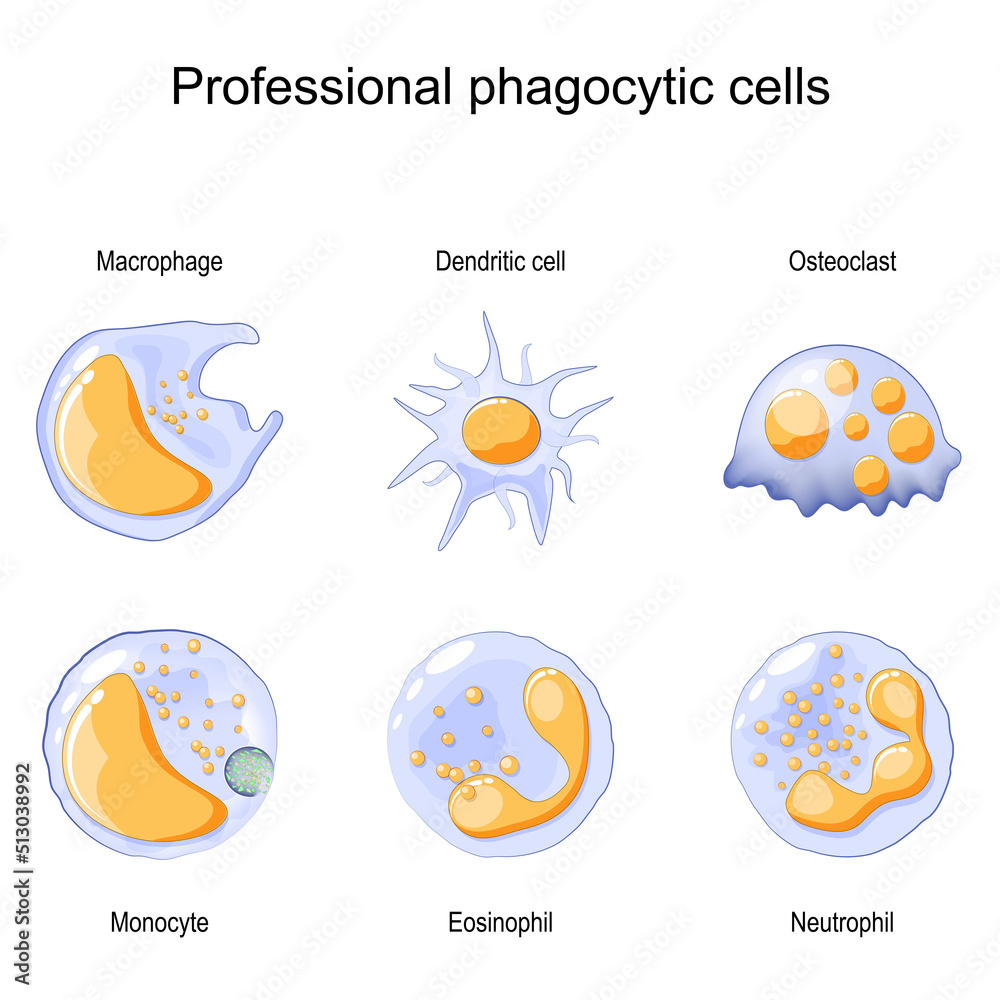

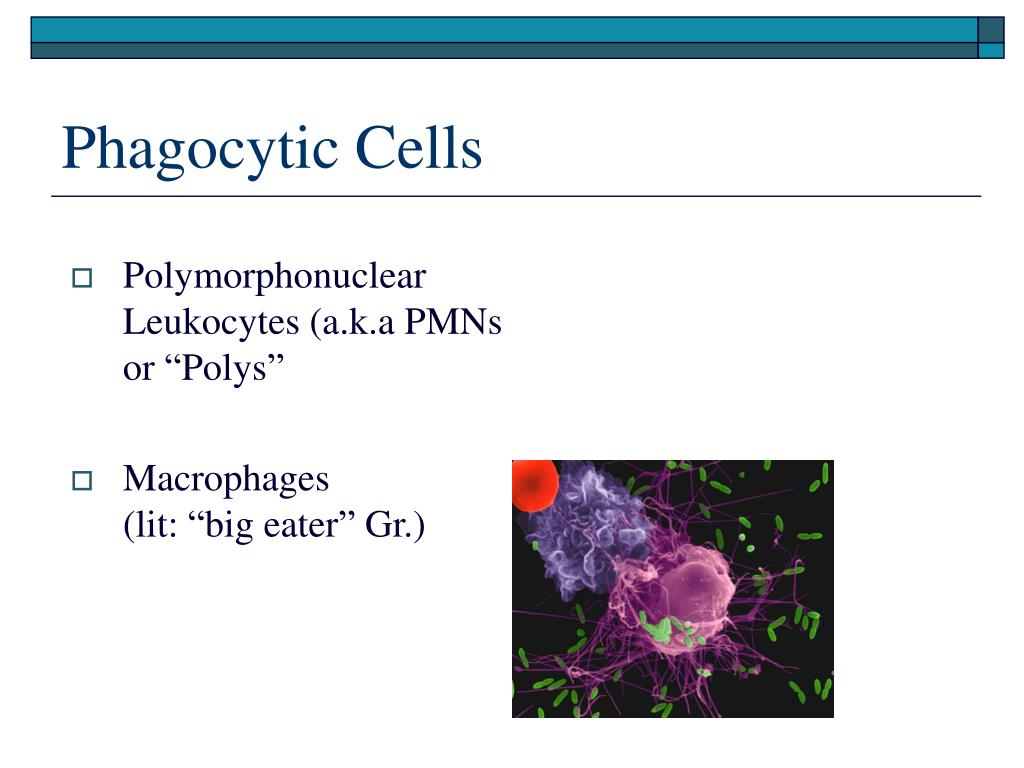

Several types of immune cells are professional phagocytes, meaning phagocytosis is one of their primary functions. These include neutrophils, macrophages, and dendritic cells.

Neutrophils: The First Responders

Neutrophils, the most abundant type of white blood cell, are typically the first responders to an infection site. They are highly efficient at engulfing bacteria and other pathogens, sacrificing themselves in the process to neutralize the threat.

Their short lifespan and high numbers make them a crucial component of the innate immune system. After phagocytosing pathogens, they often form pus, a visible sign of the immune response.

Macrophages: Versatile Defenders

Macrophages are larger phagocytic cells that reside in tissues throughout the body. Unlike neutrophils, macrophages have a longer lifespan and can perform phagocytosis multiple times.

They not only engulf pathogens but also remove dead cells and debris, playing a vital role in tissue repair. Macrophages also present antigens to T cells, bridging the gap between the innate and adaptive immune systems.

Dendritic Cells: Antigen Presenting Specialists

Dendritic cells, while capable of phagocytosis, primarily function as antigen-presenting cells. They engulf pathogens and then process and present their antigens on their surface to T cells, initiating the adaptive immune response.

This process activates T cells, which can then directly kill infected cells or activate B cells to produce antibodies. Dendritic cells are therefore a critical link between the innate and adaptive immune responses.

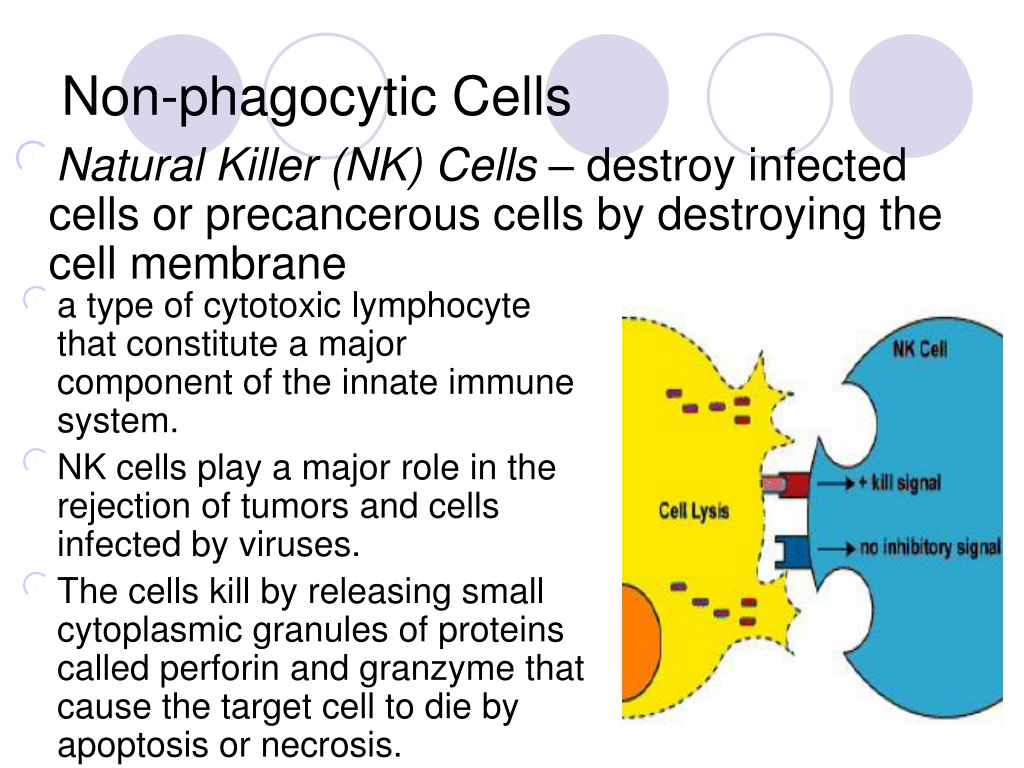

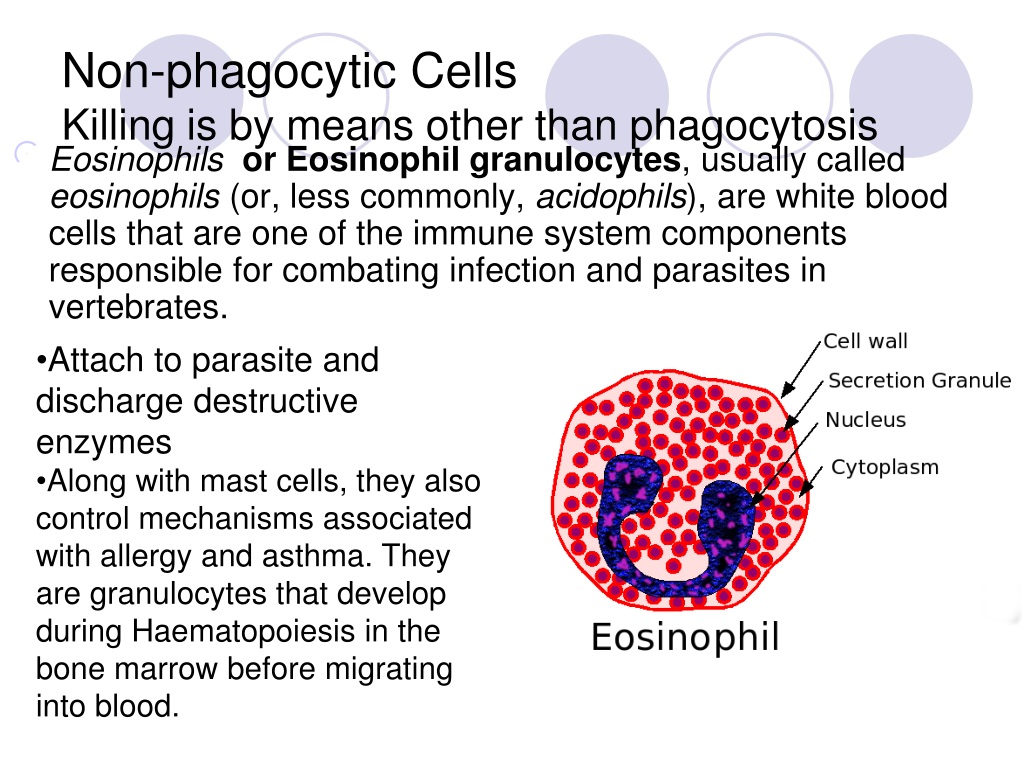

The Non-Phagocytic Immune Cell

Among the common immune cells, lymphocytes, which include T cells, B cells, and natural killer (NK) cells, are the ones that do *not* typically perform phagocytosis. Their roles are specialized to other aspects of the immune response.

Instead of engulfing pathogens, T cells directly kill infected cells, while B cells produce antibodies that neutralize pathogens and mark them for destruction by other immune cells.

Natural killer (NK) cells target and kill cells that are infected with viruses or have become cancerous. Their mechanism relies on recognizing changes on the cell surface, without phagocytosis.

"Lymphocytes recognize and respond to specific antigens via specialized receptors, but they do not typically engulf pathogens or cellular debris," explains Dr. Emily Carter, an immunologist at the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

The Significance of Specialized Immune Functions

The division of labor among immune cells is crucial for an effective immune response. While phagocytes clear pathogens and debris, lymphocytes provide targeted and long-lasting immunity.

The coordinated action of these different cell types ensures that the body can effectively defend itself against a wide range of threats. A deficiency in any of these cell types can lead to increased susceptibility to infections and other diseases.

For instance, individuals with neutropenia, a condition characterized by a low neutrophil count, are highly vulnerable to bacterial infections. Similarly, defects in T cell or B cell function can result in severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), a life-threatening condition.

Conclusion

In summary, while neutrophils, macrophages, and dendritic cells are professional phagocytes responsible for engulfing and digesting pathogens and debris, lymphocytes, including T cells, B cells, and NK cells, are *not* phagocytic. Lymphocytes play a crucial role in adaptive immunity through targeted killing and antibody production.

Understanding the distinct roles of each immune cell type is essential for comprehending the complexities of the immune system and developing effective strategies to combat diseases. Further research into these intricate mechanisms will undoubtedly lead to improved diagnostics and treatments for a wide range of immunological disorders.

By continuing to unravel the mysteries of the immune system, we can unlock new possibilities for preventing and treating diseases, ultimately improving human health and well-being. Learning which cells do *not* engage in phagocytosis is a crucial step in understanding the full picture.