Which Of The Following Is Not A Profitability Ratio

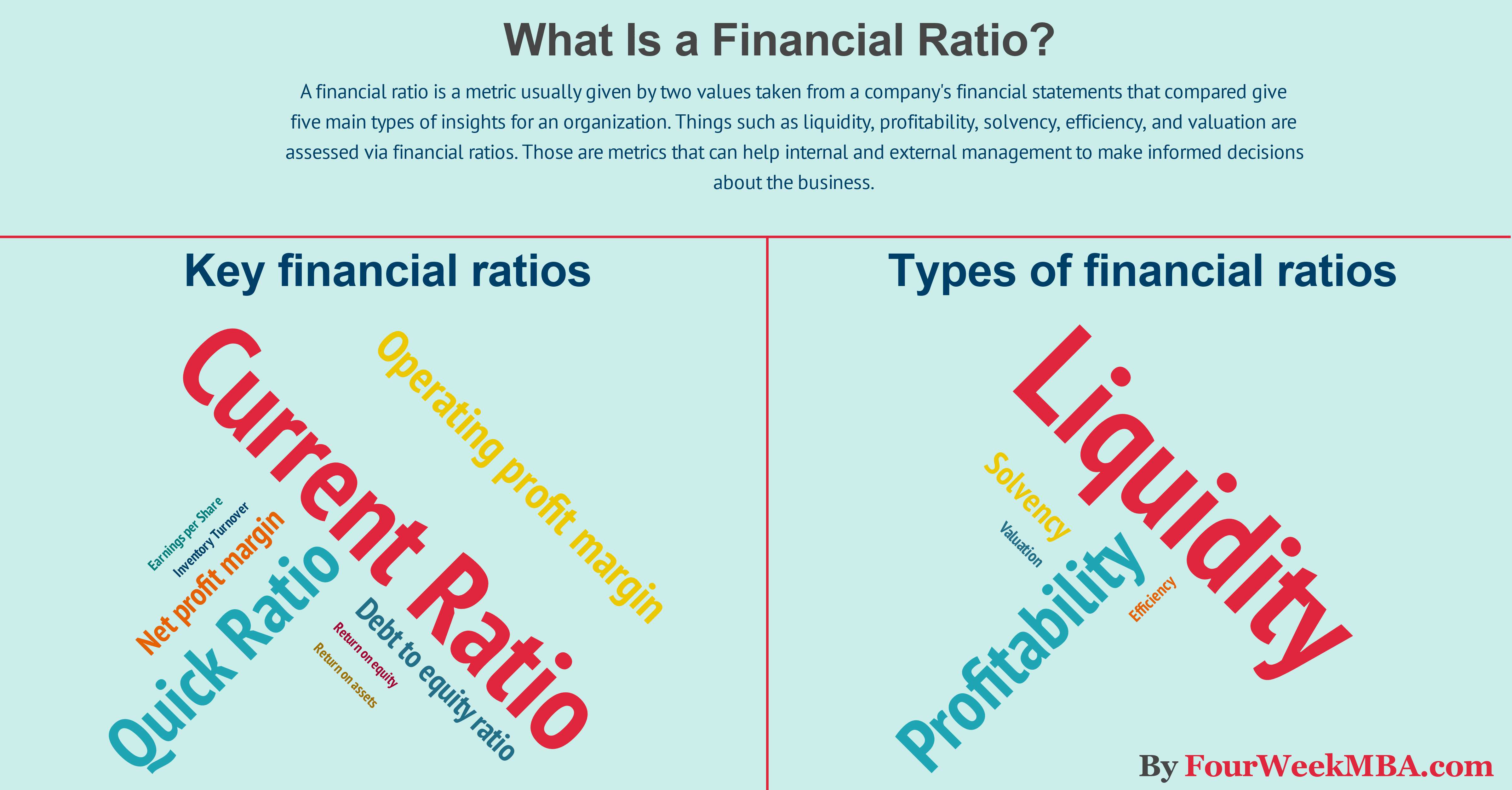

In the high-stakes world of finance, accurately assessing a company's health is paramount. Investors, analysts, and even internal management rely on a range of financial ratios to dissect performance and predict future prospects. But a single misstep in understanding these metrics can lead to flawed conclusions, potentially impacting investment decisions and strategic planning.

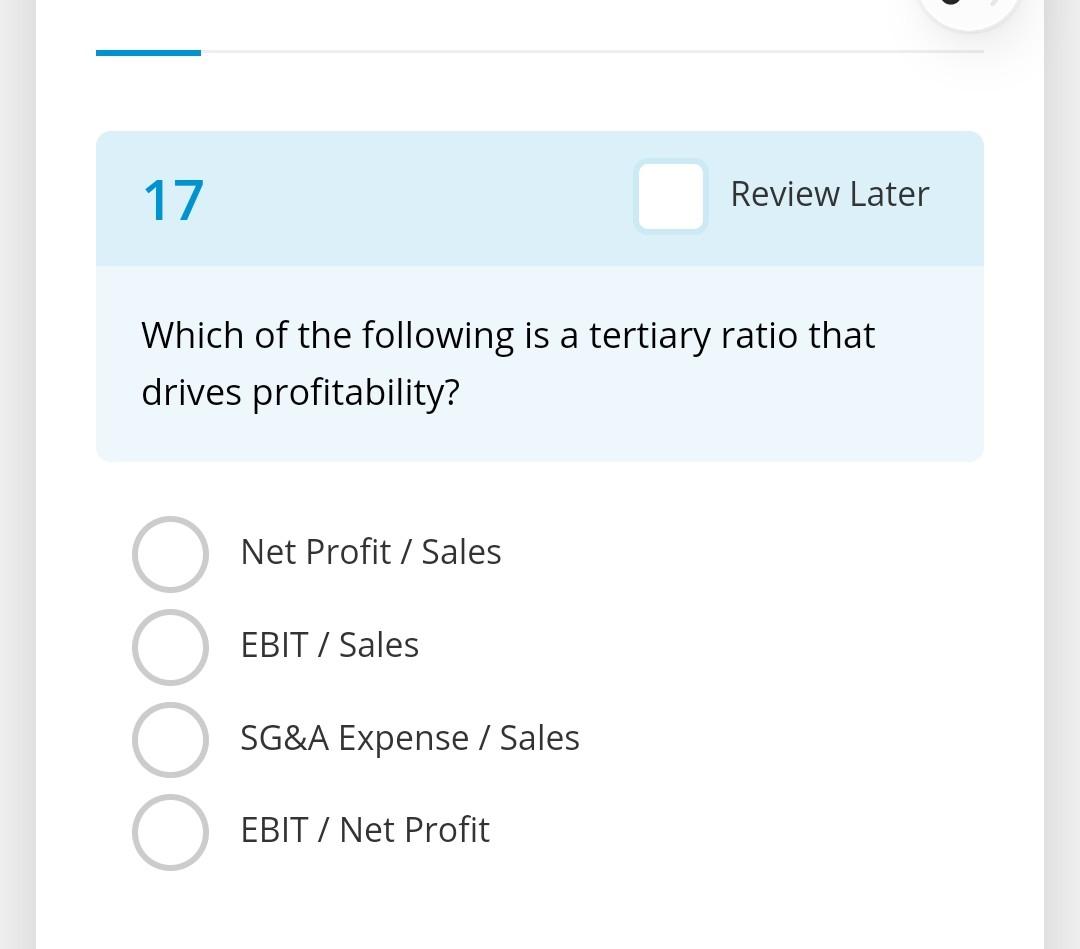

The question of "Which of the following is not a profitability ratio?" cuts to the heart of financial literacy. This seemingly simple query unveils a deeper need to distinguish between different categories of financial ratios, specifically isolating those that truly measure a company's ability to generate profit from its operations and assets.

Understanding Profitability Ratios

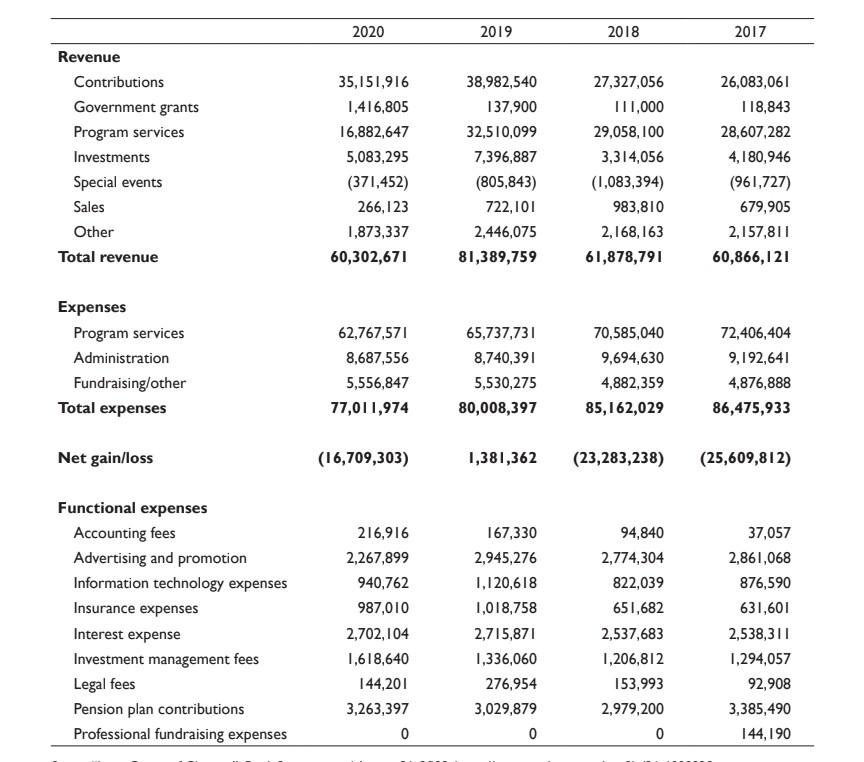

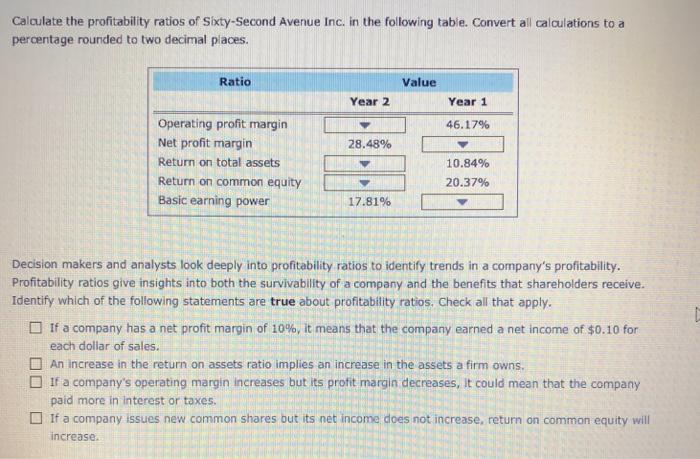

Profitability ratios are a class of financial metrics used to assess a company's ability to generate earnings relative to its revenue, operating costs, balance sheet assets, or shareholders' equity over a period of time. They provide insights into how efficiently a company is using its resources to create profit. These ratios are essential tools for investors and analysts looking to gauge a company's financial health and sustainability.

Common Profitability Ratios

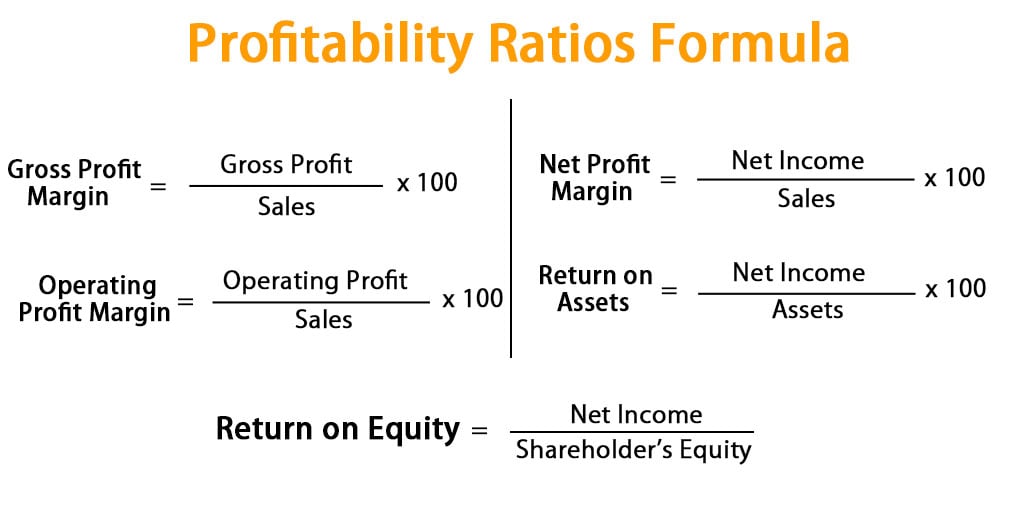

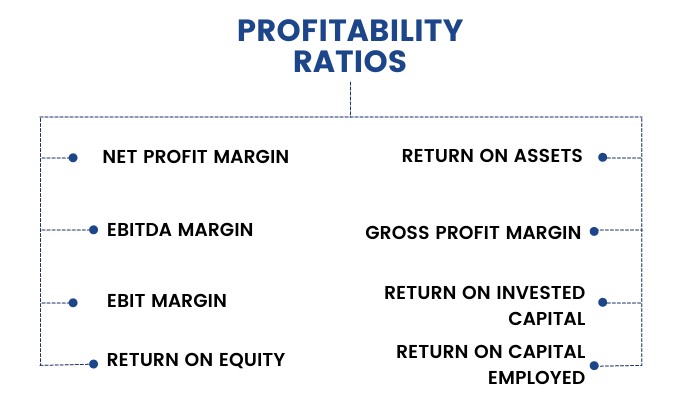

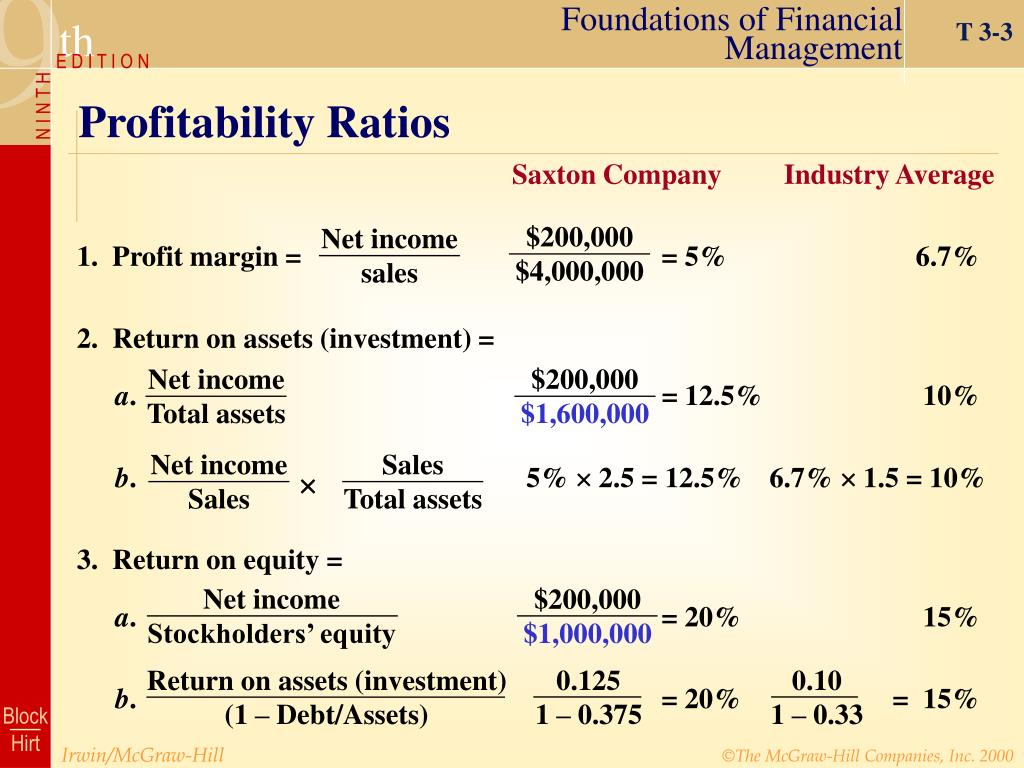

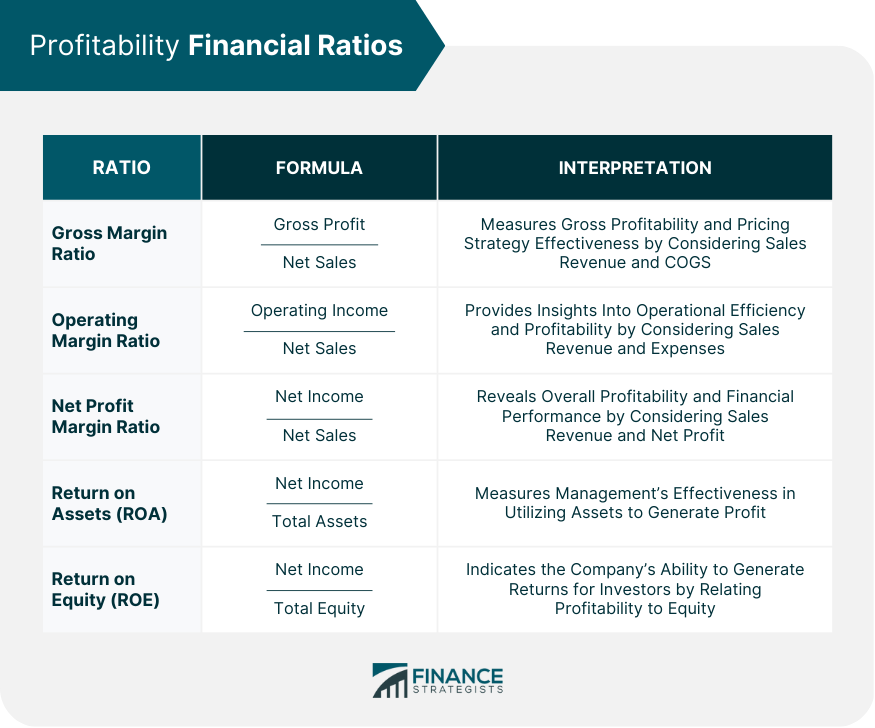

Gross Profit Margin, Net Profit Margin, Return on Assets (ROA), and Return on Equity (ROE) are among the most frequently used and widely recognized profitability ratios.

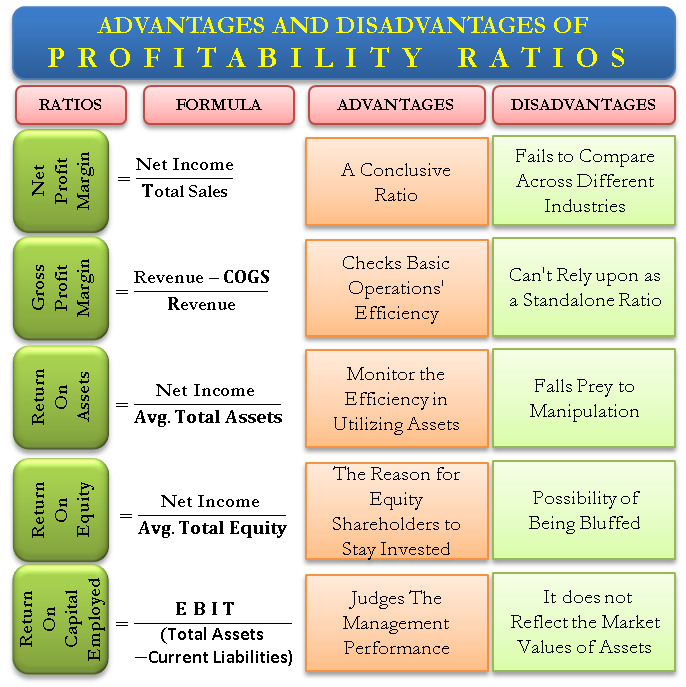

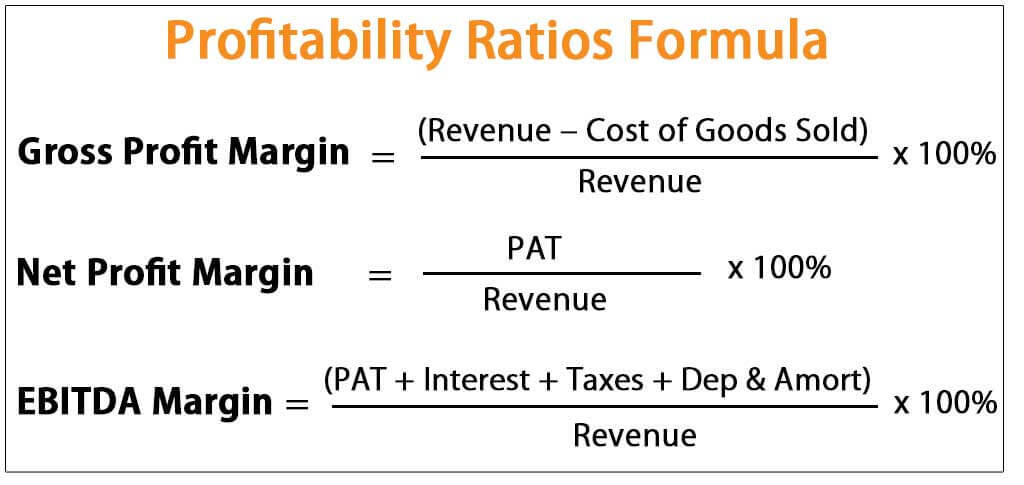

Gross Profit Margin measures the percentage of revenue remaining after deducting the cost of goods sold (COGS). It indicates how efficiently a company manages its production and pricing strategies.

Net Profit Margin, on the other hand, reveals the percentage of revenue that translates into profit after all expenses, including taxes and interest, are accounted for. A high net profit margin indicates strong overall financial performance.

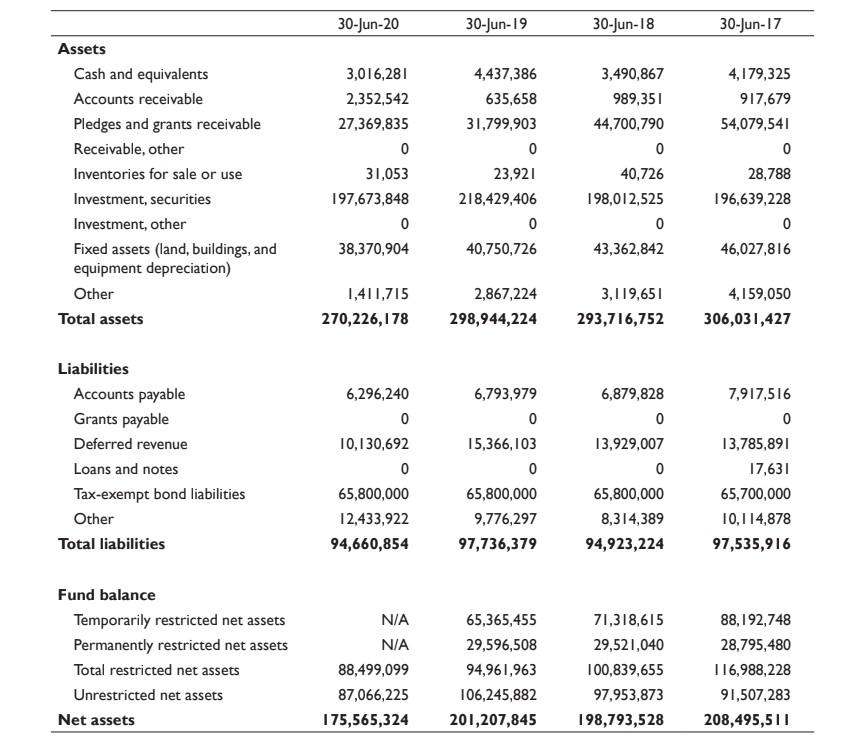

Return on Assets (ROA) calculates how effectively a company utilizes its assets to generate profit. ROA offers insight into management's skill in using a company's resources.

Return on Equity (ROE) measures the return generated for shareholders' investment. It is a key indicator of profitability from the shareholders' perspective.

Liquidity Ratios: A Distinct Category

In contrast to profitability ratios, liquidity ratios assess a company's ability to meet its short-term obligations. These ratios focus on the relationship between current assets and current liabilities, revealing whether a company has enough readily available assets to cover its immediate debts.

Examples include the current ratio, quick ratio (also known as the acid-test ratio), and cash ratio. A high current ratio suggests a company is well-positioned to pay its short-term debts.

A critical example of a non-profitability ratio is the Current Ratio. This ratio, calculated by dividing current assets by current liabilities, measures a company's ability to pay off its short-term obligations with its current assets. The current ratio, while important, doesn't directly measure a company's profitability.

Distinguishing Between Ratio Types

The key difference lies in the focus. Profitability ratios gauge earnings performance, while liquidity ratios assess the ability to meet short-term financial obligations.

Confusing these categories can lead to inaccurate financial analysis. For example, a company with a high current ratio (strong liquidity) may still have low profit margins (poor profitability), indicating underlying operational inefficiencies.

The Importance of Context

When analyzing financial ratios, it's crucial to consider the context of the industry. What is considered a good ratio in one industry might be considered poor in another. Understanding industry benchmarks is essential for effective financial analysis.

Comparing a company's ratios to its competitors and its own historical performance provides valuable insights. A declining profit margin, even if still positive, may signal potential problems.

Potential Pitfalls

Relying solely on ratios without understanding the underlying numbers can be misleading. Ratios can be manipulated through accounting practices, so a thorough examination of the financial statements is always necessary.

For example, a company could artificially inflate its current ratio by delaying payments to suppliers. This highlights the importance of digging deeper than just the surface-level ratios.

Additionally, external economic factors can significantly impact a company's financial performance. A recession, for instance, could negatively affect both profitability and liquidity ratios.

Conclusion

Accurately identifying and interpreting financial ratios is crucial for informed decision-making in finance. Understanding the distinct purpose of profitability ratios versus other categories, such as liquidity ratios, is paramount.

The Current Ratio is not a profitability ratio; it measures liquidity. Investors and analysts should always consider the context, compare ratios to industry benchmarks, and examine the underlying financial statements to gain a comprehensive understanding of a company's financial health.

Looking ahead, as financial markets become increasingly complex, the need for robust financial literacy will only grow. A solid grasp of financial ratios will remain a cornerstone of successful investing and strategic management.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/profitability-ratios-508804002f2c42448463becc3b37e79b.jpg)