Which Of The Following Is Not A Public Good

In an era defined by complex economic and social challenges, understanding the nature of public goods is more critical than ever. The debate over what constitutes a public good – and, conversely, what falls outside this classification – has profound implications for government policy, market efficiency, and the well-being of citizens.

Misclassifying goods can lead to under-provision, market failures, and inequities. This article delves into the characteristics of public goods, examines examples of both public and private goods, and ultimately seeks to clarify what does *not* qualify as a public good, offering a framework for informed decision-making in the public sphere.

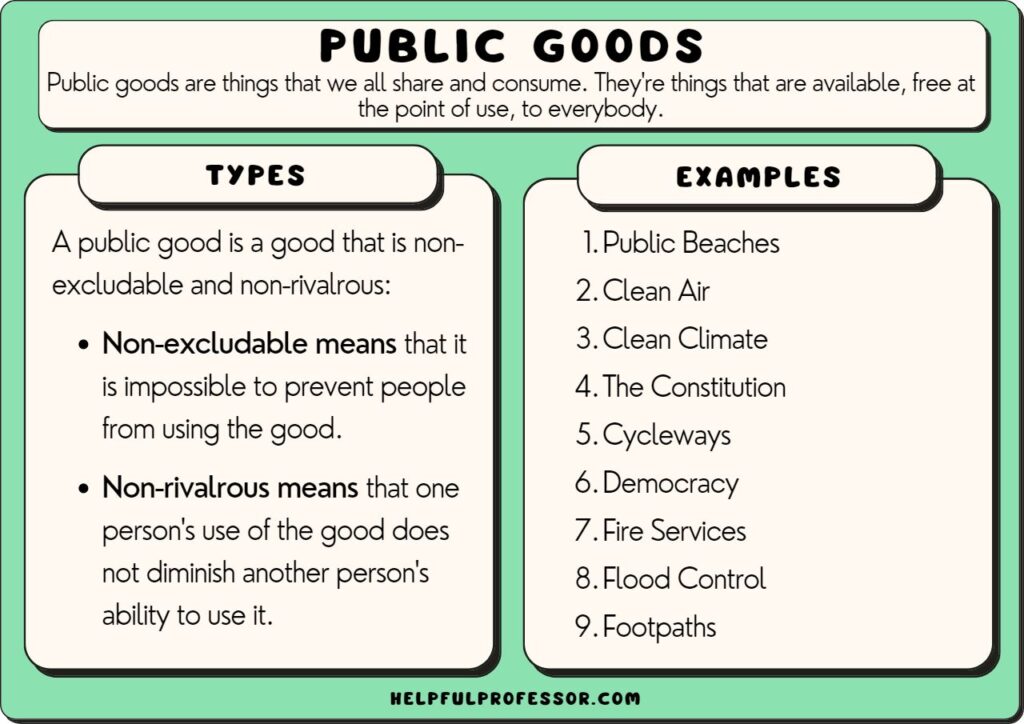

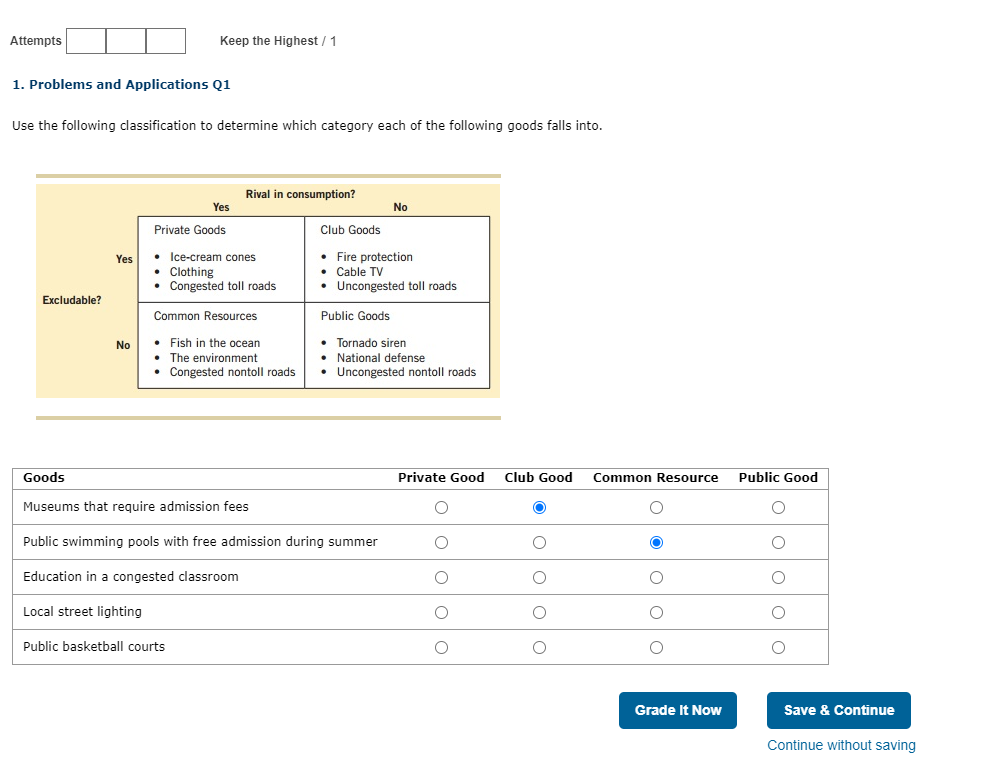

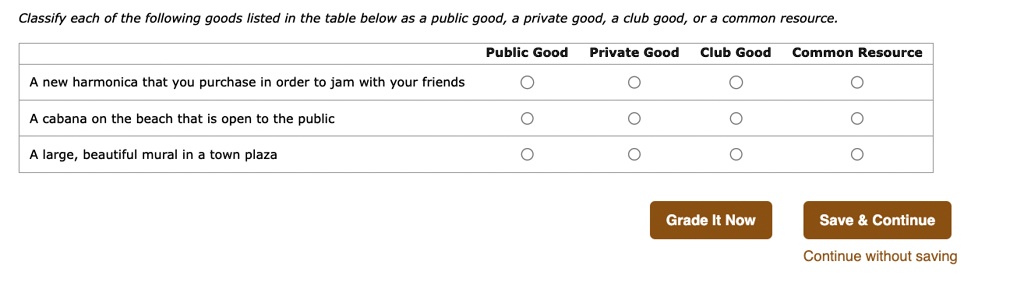

Defining Public Goods: Key Characteristics

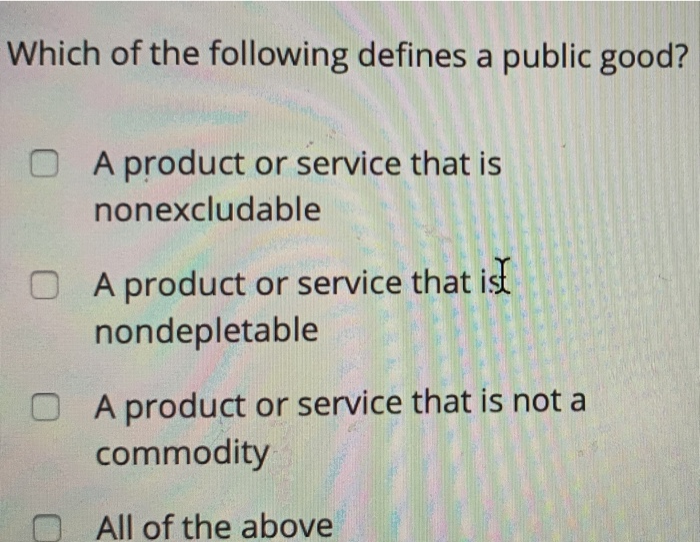

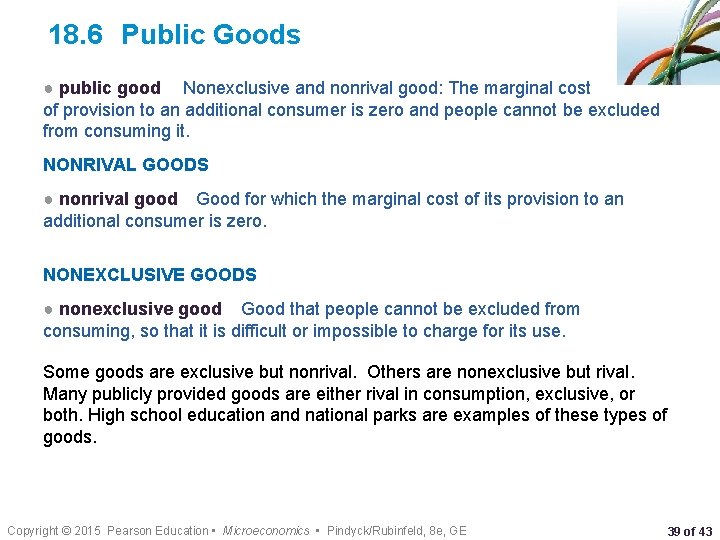

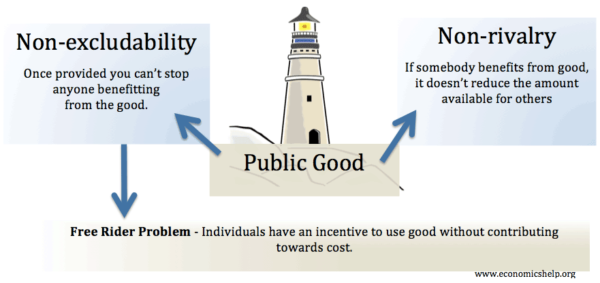

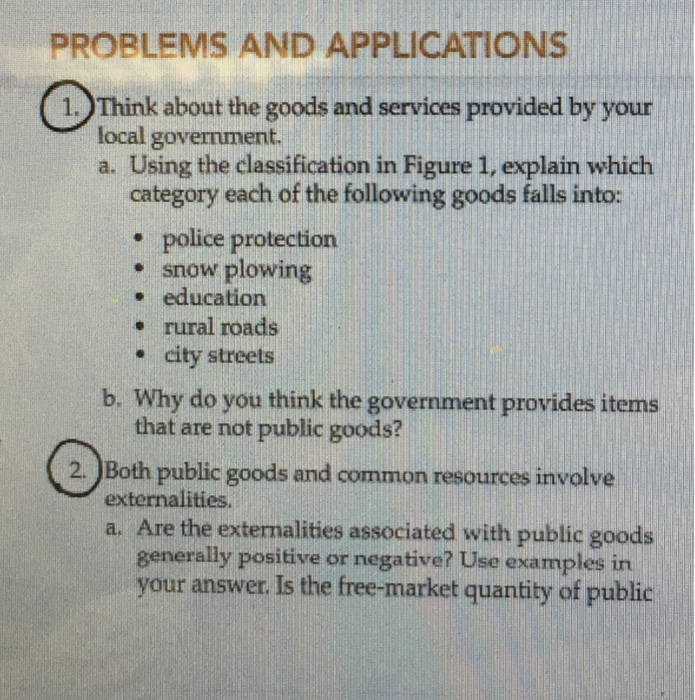

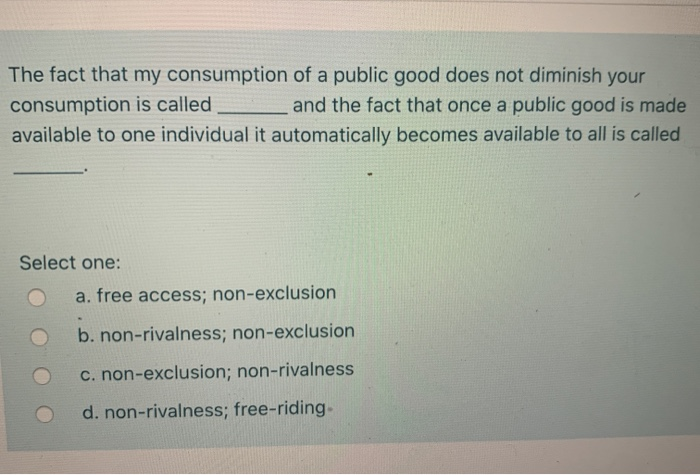

A public good is defined by two key characteristics: non-excludability and non-rivalry. Non-excludability means it's impossible, or prohibitively expensive, to prevent individuals from enjoying the benefit of the good, even if they don't pay for it.

Non-rivalry signifies that one person's consumption of the good doesn't diminish its availability to others. Classic examples of public goods include national defense and clean air.

Examples of Public Goods and Near-Public Goods

National defense provides security to all citizens, regardless of whether they individually contribute to its funding through taxes. Consumption by one citizen does not reduce the protection available to others.

Clean air is another example. Everyone benefits from a cleaner environment, and breathing clean air doesn't reduce its availability to others. These two fulfill the requirements of public goods.

Street lighting and public parks often considered near-public goods. While generally non-excludable, they may exhibit some degree of rivalry at peak times, such as crowded parks.

Goods That Are *Not* Public Goods

Many goods and services are often mistaken for public goods. However, they lack the necessary characteristics of non-excludability and non-rivalry. Understanding why they don't qualify is essential for effective policy.

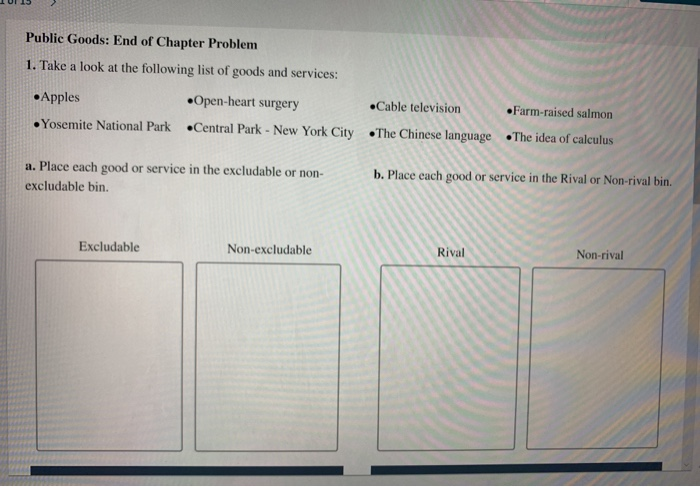

Private Goods: Excludable and Rivalrous

Private goods are excludable and rivalrous. This means individuals can be prevented from consuming the good if they don't pay for it, and one person's consumption diminishes its availability to others.

Examples include food, clothing, and cars. If you don't pay for a sandwich, you can't eat it, and if you eat it, no one else can.

Club Goods: Excludable but Non-Rivalrous

Club goods are excludable but non-rivalrous, at least up to a certain point. Examples include cable television, private parks and golf clubs.

Only members can access them. Consumption by one member doesn't necessarily diminish availability for others until capacity is reached.

Common-Pool Resources: Non-Excludable but Rivalrous

Common-pool resources are non-excludable but rivalrous. These resources are available to everyone, but one person's consumption can reduce the availability for others.

Fisheries, forests, and groundwater are classic examples. Overfishing, deforestation, and excessive water usage deplete the resource for everyone.

Why is Classification Important?

Accurate classification of goods is crucial for efficient resource allocation. Public goods often require government intervention to ensure adequate provision due to the free-rider problem.

Private goods can be efficiently provided by the market. Misclassification can lead to market failures or inefficient government spending.

The Role of Technology and Changing Classifications

Technological advancements can blur the lines between different types of goods. For instance, digital content, once easily pirated (non-excludable), can now be protected by DRM (excludable).

This shifts it from a near-public good to a club good. Similarly, congestion pricing can make roads excludable during peak hours.

Case Studies: Misclassifications and Their Consequences

Consider healthcare. In many countries, healthcare is considered a merit good, a good that society believes everyone should have access to regardless of their ability to pay.

While some aspects of public health (e.g., disease prevention) have public good characteristics, direct medical care is generally rivalrous and often excludable. Treating it solely as a public good can lead to unsustainable funding models.

Another example is education. While a more educated population benefits society as a whole, direct education is a private good. One student's consumption of educational resources prevents them from being consumed by another.

Future Considerations: Adapting to a Changing World

The evolving nature of technology and societal needs requires a continuous reassessment of how we classify goods. Policymakers must carefully consider the characteristics of each good when designing policies related to provision, pricing, and regulation.

Ignoring these fundamental economic principles can lead to inefficient resource allocation. This also leads to unintended consequences.

Conclusion: A Framework for Informed Decision-Making

Identifying what is *not* a public good is just as important as understanding what is. Recognizing the distinctions between private goods, club goods, and common-pool resources allows for more targeted and effective policy interventions.

By applying the principles of non-excludability and non-rivalry, policymakers can make informed decisions that promote both economic efficiency and social welfare, ensuring resources are allocated in a manner that best serves the needs of society.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Term-Definitions_publicgood.asp-9aa537878b404c3393cb87845e26f9d2.jpg)