Assets Are Recorded In The Balance Sheet In Order Of

Imagine strolling through a meticulously organized library. Each book, each manuscript, each digital file has its designated place, arranged in a way that makes finding information both logical and efficient. Now, picture a company's financial health as this library; its balance sheet is the catalog, and the items within are its assets.

Understanding how these assets are ordered – from cash in hand to long-term investments – is crucial to deciphering the true financial story of a business. This article will explore the principles behind this order, revealing why and how assets are presented on the balance sheet.

Understanding the Balance Sheet: A Financial Snapshot

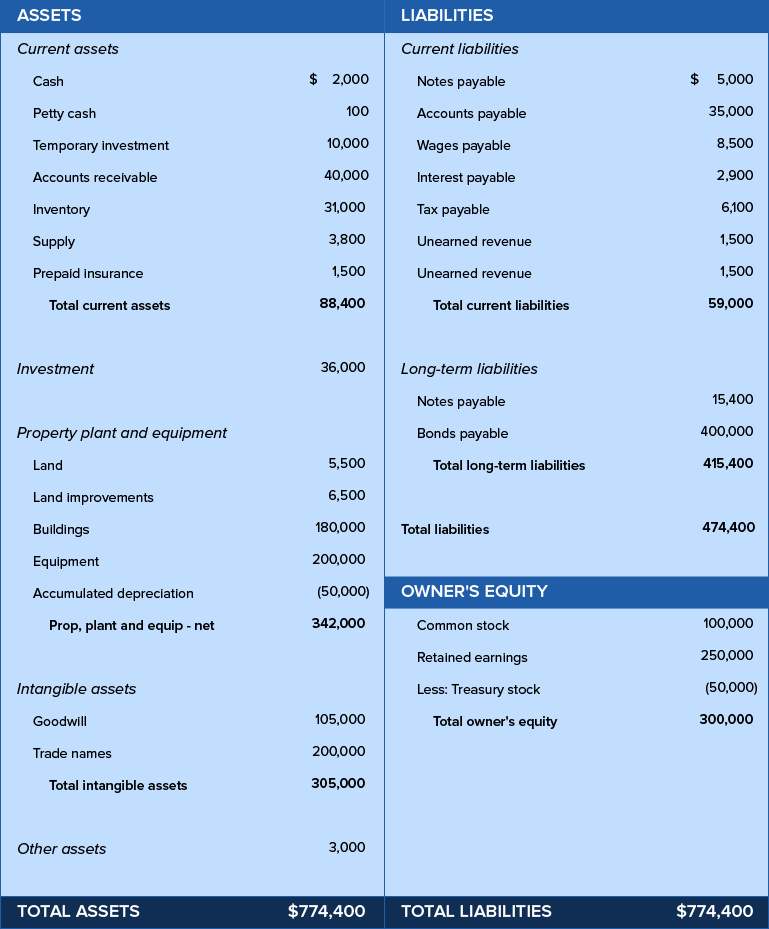

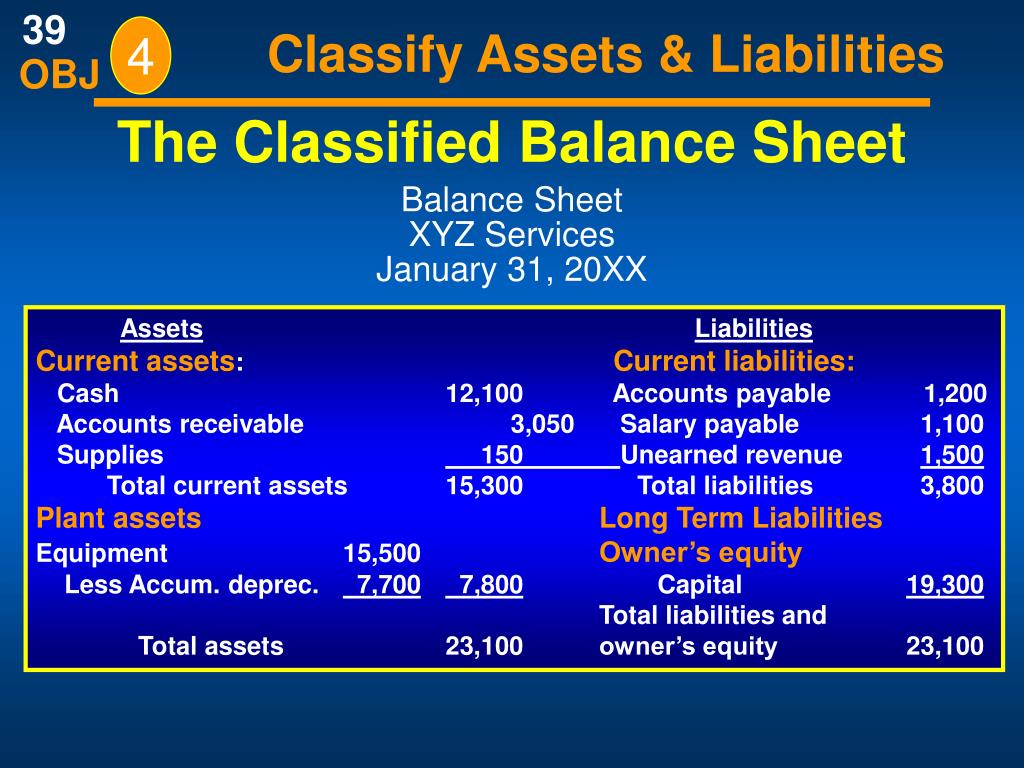

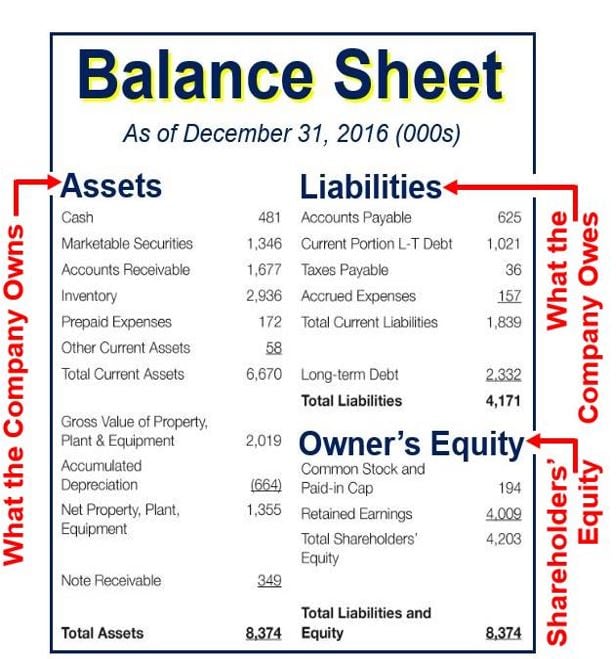

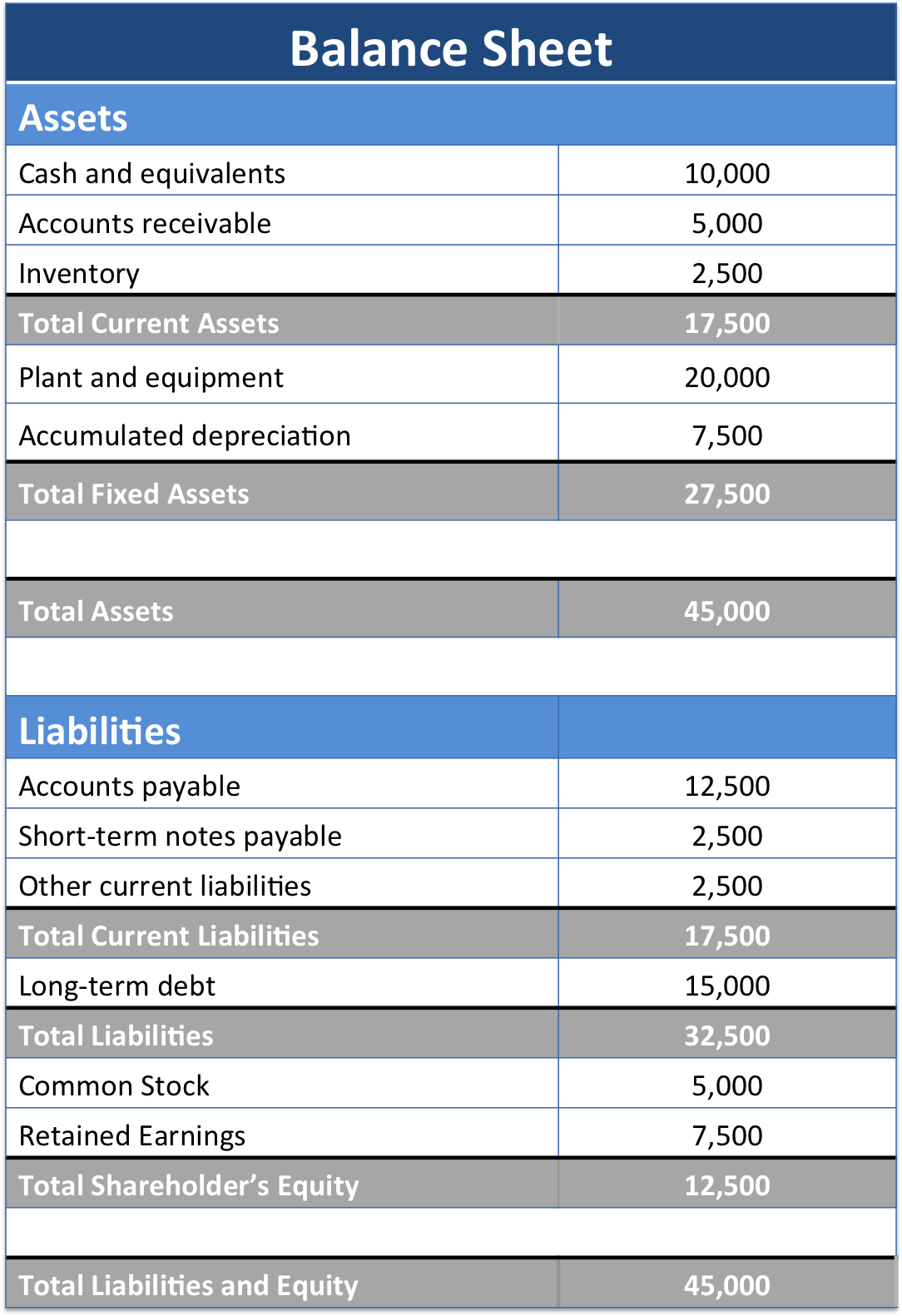

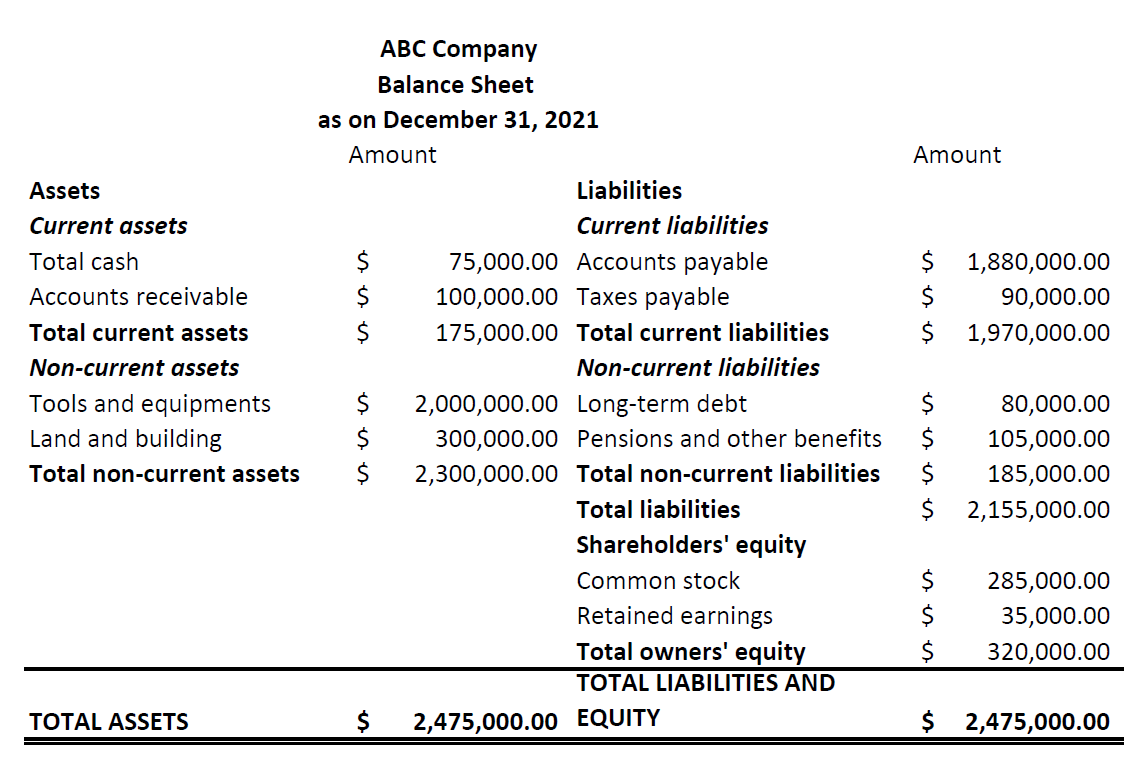

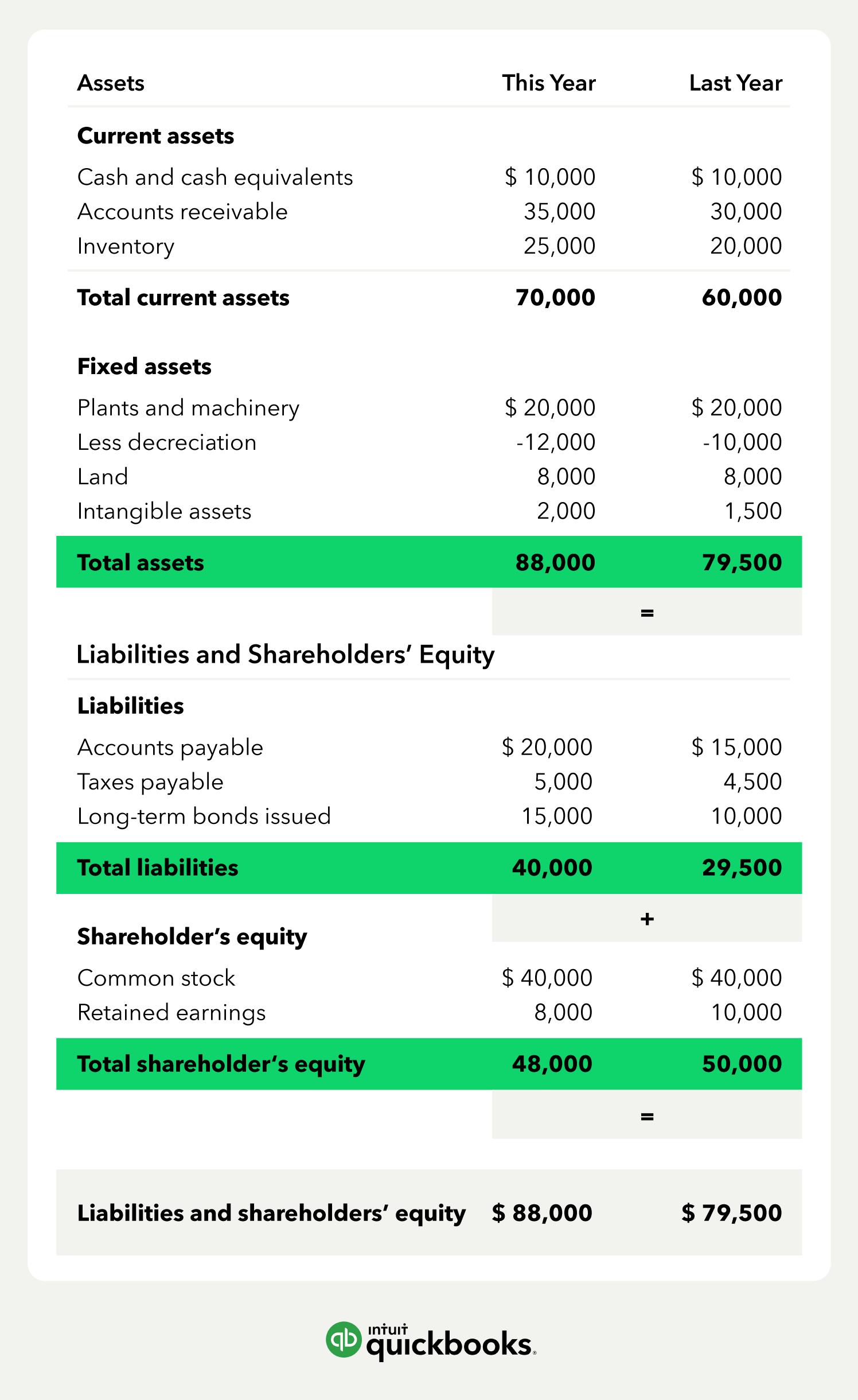

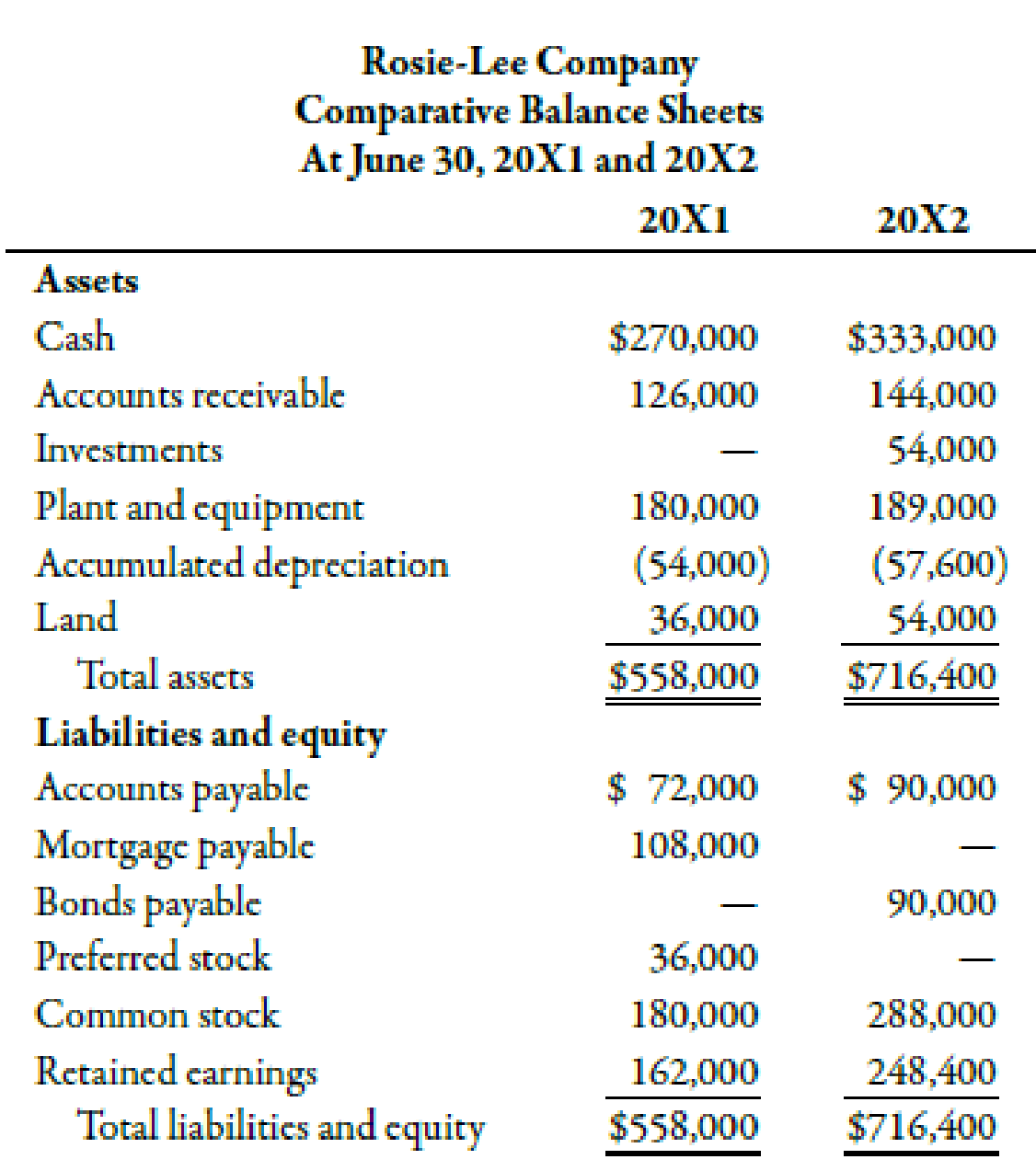

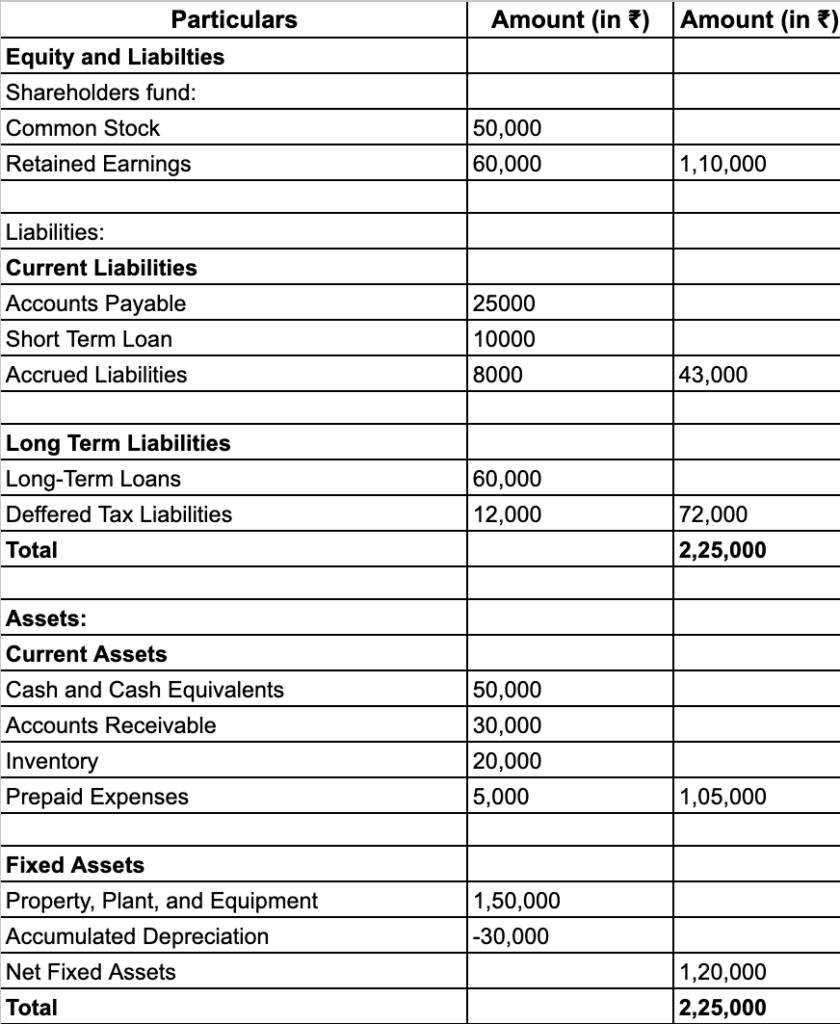

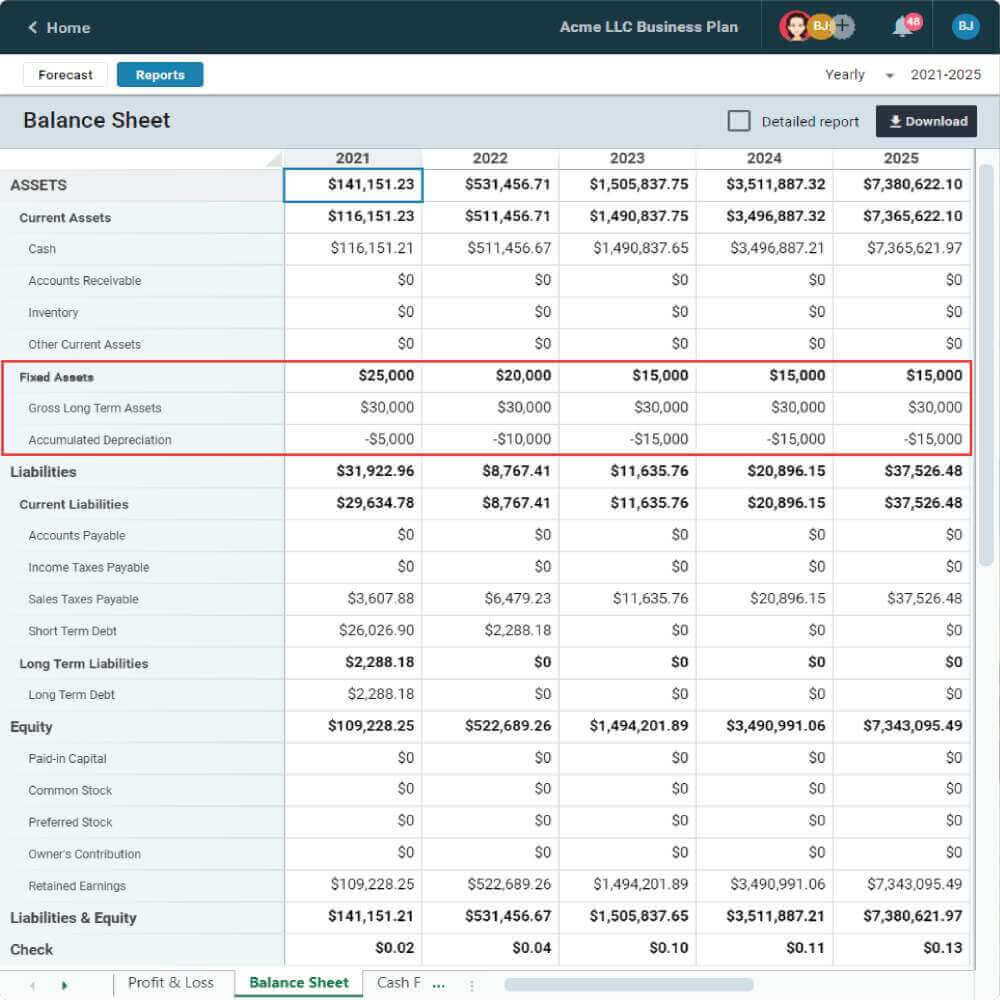

The balance sheet, often called the statement of financial position, is one of the core financial statements that businesses use. It provides a snapshot of a company's assets, liabilities, and equity at a specific point in time.

Think of it as a photograph of a company's financial standing at a given moment, capturing what it owns (assets), what it owes (liabilities), and the owners' stake in the company (equity).

The fundamental accounting equation that underpins the balance sheet is: Assets = Liabilities + Equity.

The Liquidity Principle: Guiding the Order of Assets

Assets on a balance sheet aren't listed randomly. The order reflects a fundamental principle known as liquidity.

Liquidity refers to how easily an asset can be converted into cash.

The more easily and quickly an asset can be turned into cash, the higher its liquidity and the earlier it appears on the balance sheet.

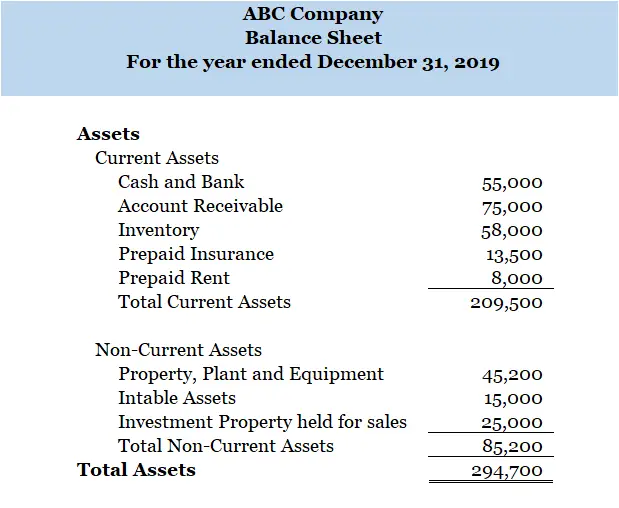

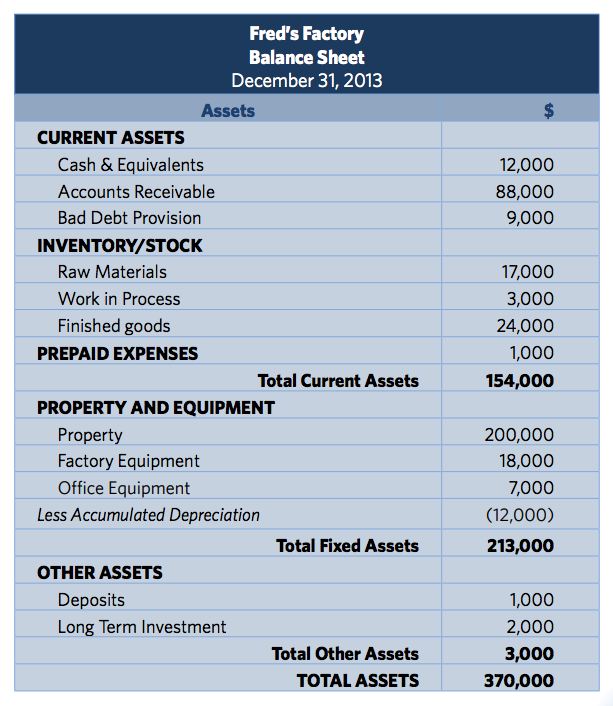

Current Assets: The Front Line

Current assets are those expected to be converted to cash, sold, or consumed within one year or one operating cycle, whichever is longer.

They represent the company's immediate resources for meeting its short-term obligations.

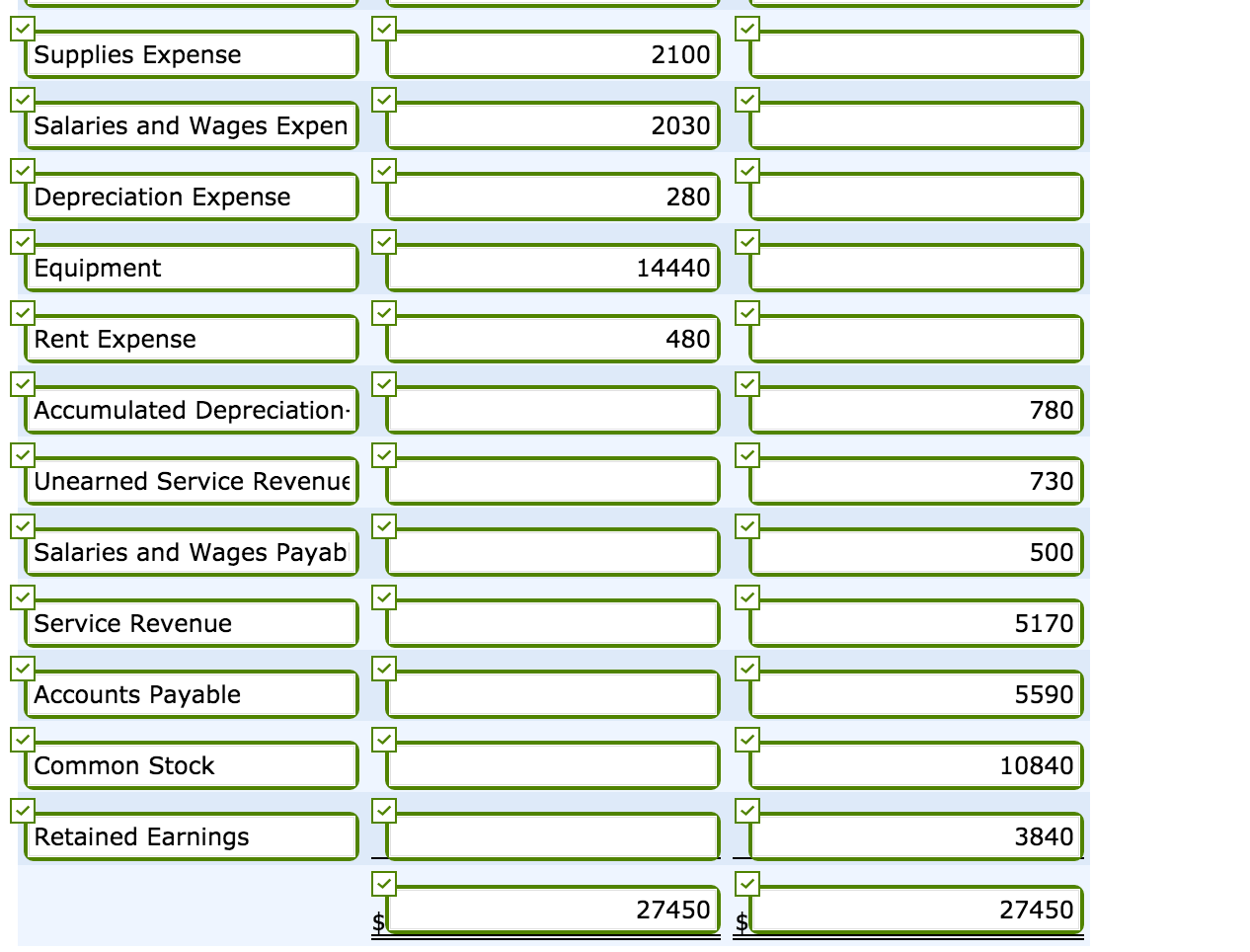

Here's the typical order of current assets:

Cash and Cash Equivalents

Cash is king! It's the most liquid asset of all.

This includes actual currency on hand, checking accounts, and readily available funds.

Cash equivalents are short-term, highly liquid investments that can be easily converted to cash with minimal risk of price change (e.g., treasury bills, money market funds).

Marketable Securities

These are short-term investments that can be readily bought and sold in the market.

Examples include stocks and bonds held for a short duration.

Their liquidity makes them a step down from cash but still highly convertible.

Accounts Receivable

Accounts receivable represents the money owed to the company by its customers for goods or services already delivered.

It's an expectation of future cash inflow.

The speed of conversion depends on the company's credit terms and collection efficiency.

Inventory

Inventory consists of the goods a company intends to sell to customers.

This includes raw materials, work-in-progress, and finished goods.

Selling inventory and then collecting on those sales turns inventory into cash, making it less liquid than accounts receivable.

Prepaid Expenses

Prepaid expenses are payments a company has made in advance for goods or services that haven't yet been received or used.

An example could be prepaid insurance or rent.

These are considered assets because they represent a future benefit; however, they are the least liquid of current assets as they don’t convert to cash.

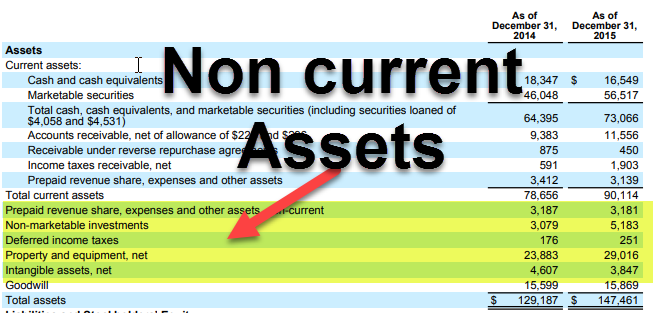

Non-Current Assets: The Long Game

Non-current assets are those not expected to be converted into cash within one year. They represent a company's long-term investments and operational infrastructure.

These assets are essential for supporting the company's ongoing operations and growth.

Here's the typical order of non-current assets, moving from relatively more tangible to less tangible:

Property, Plant, and Equipment (PP&E)

PP&E includes tangible, long-lived assets used in a company's operations.

Examples include land, buildings, machinery, and equipment.

These assets are generally depreciated over their useful lives, reflecting their gradual consumption.

Long-Term Investments

These are investments held for longer than one year.

They can include investments in stocks, bonds, real estate, or other companies.

Their liquidity depends on the specific investment and market conditions.

Intangible Assets

Intangible assets lack physical substance but provide future economic benefits.

Examples include patents, trademarks, copyrights, and goodwill.

Goodwill arises when one company acquires another for a price exceeding the fair value of its identifiable net assets. Intangible assets are the least liquid.

Why Does Asset Order Matter?

The order of assets on the balance sheet isn't just for neatness. It provides valuable insights for stakeholders.

Investors and creditors can quickly assess a company's liquidity and short-term financial health.

A high proportion of liquid assets suggests a company is better positioned to meet its immediate obligations.

Analyzing the composition of assets helps understand a company's business model and strategy.

For example, a manufacturing company would typically have a significant investment in PP&E, while a technology company might have more intangible assets.

Creditors may be more willing to lend to a company with a stronger current asset position, indicating a greater ability to repay loans.

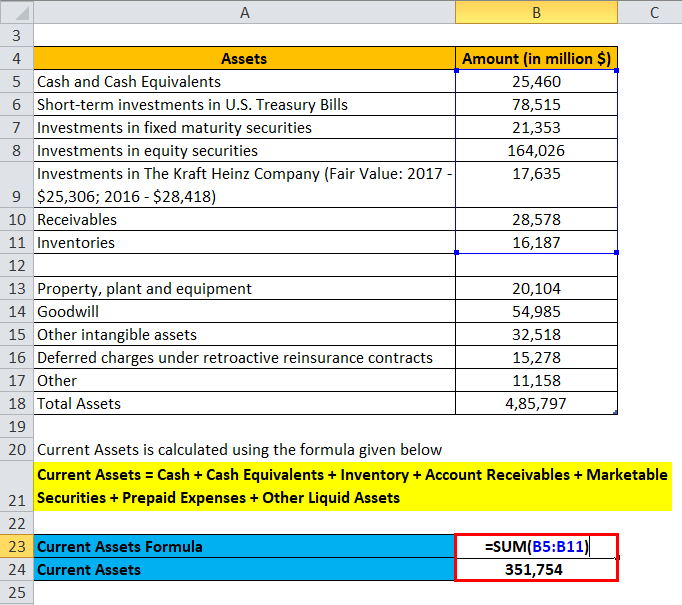

Real-World Examples

Consider Apple Inc. Looking at their consolidated balance sheets, you'd find cash and marketable securities dominating the current assets.

This reflects Apple's strong cash flow and ability to maintain a highly liquid position.

Now, let's think about Ford Motor Company. Ford's balance sheet would likely show a substantial investment in PP&E related to its manufacturing facilities.

It would also have a significant amount of inventory (vehicles) for sale.

The comparison highlights how the asset composition reflects the underlying business operations.

Conclusion: Beyond the Numbers

Understanding how assets are presented on the balance sheet based on liquidity is more than just an accounting exercise. It's about gaining a deeper understanding of a company's financial health and operational strategy.

The liquidity principle, guiding the order of assets, helps stakeholders quickly assess a company's ability to meet its obligations and pursue its long-term goals.

By carefully examining the composition and arrangement of assets, we can unlock valuable insights into the financial narrative of any business, transforming raw numbers into a compelling story.