Fundamental Patterns Of Knowing In Nursing

In the high-stakes world of healthcare, where seconds can mean the difference between life and death, the knowledge guiding nurses' actions is paramount. But what *exactly* constitutes that knowledge, and how is it acquired and applied? The answers are far more nuanced than rote memorization of medical facts.

A comprehensive understanding of the "fundamental patterns of knowing in nursing" is critical, and it's under increasing scrutiny as healthcare becomes ever more complex.

This article delves into these essential knowledge domains, exploring their application in practice and the ongoing efforts to refine and expand them, ultimately improving patient outcomes. The framework itself is constantly evolving, reflecting the dynamic landscape of healthcare and the growing demands placed on nursing professionals.

The Core Patterns Unveiled

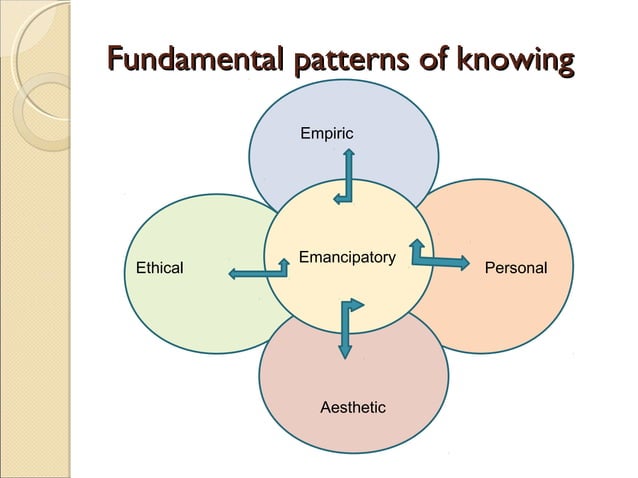

The concept of fundamental patterns of knowing was first articulated significantly by Barbara Carper in her seminal 1978 article, "Fundamental Patterns of Knowing in Nursing".

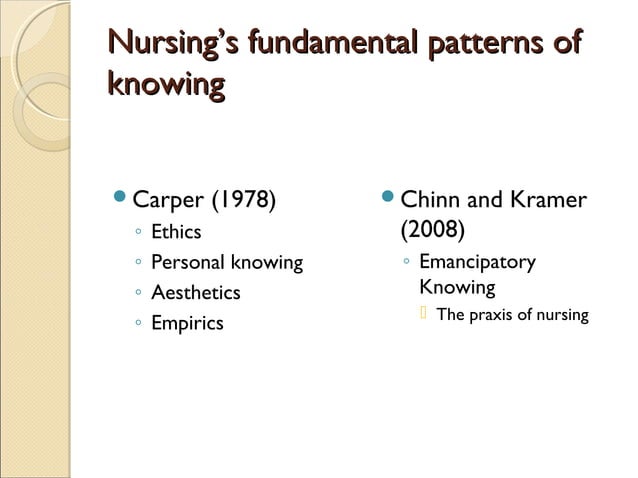

These patterns provide a crucial framework for understanding the multiple dimensions of knowledge that nurses utilize. They go beyond simply knowing *what* to do; they encompass *why* it’s done and *how* it impacts the patient on a holistic level. The four original patterns are: Empirical Knowing, Ethical Knowing, Aesthetic Knowing, and Personal Knowing.

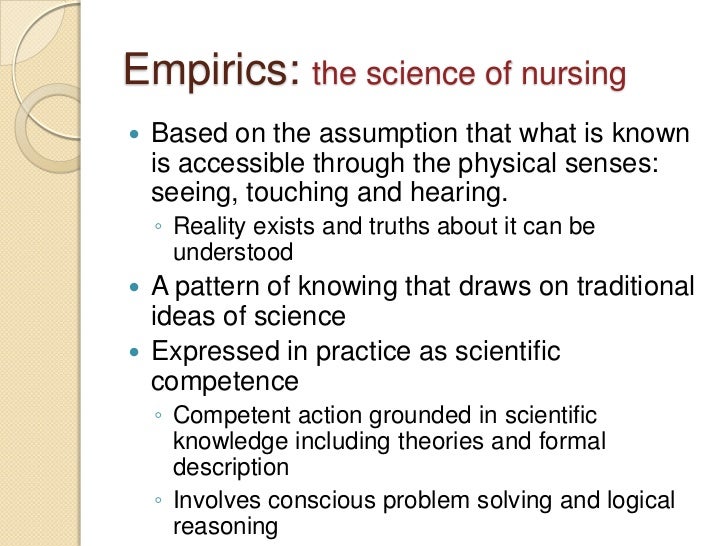

Empirical Knowing: The Science of Nursing

Empirical knowing, also referred to as the science of nursing, is the type of knowledge derived from scientific evidence, research, and objective facts.

It encompasses the theoretical and factual knowledge necessary for understanding diagnoses, treatments, and interventions. For example, understanding the physiological effects of a medication or the proper technique for wound care falls under this domain.

Nursing programs emphasize empirical knowledge heavily, equipping graduates with the scientific foundation for their practice. Organizations such as the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) actively support studies in this area.

Ethical Knowing: Navigating Moral Dilemmas

Ethical knowing concerns moral principles, values, and obligations that guide nursing practice. Nurses frequently encounter ethical dilemmas requiring them to make difficult choices balancing patient autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice.

For example, a nurse might face an ethical conflict when a patient refuses a life-saving treatment. This requires careful consideration of the patient's rights, the nurse's professional responsibilities, and the potential consequences of both action and inaction.

Professional codes of ethics, such as those published by the American Nurses Association (ANA), provide a framework for ethical decision-making, but nurses often need to exercise considerable judgment in complex situations.

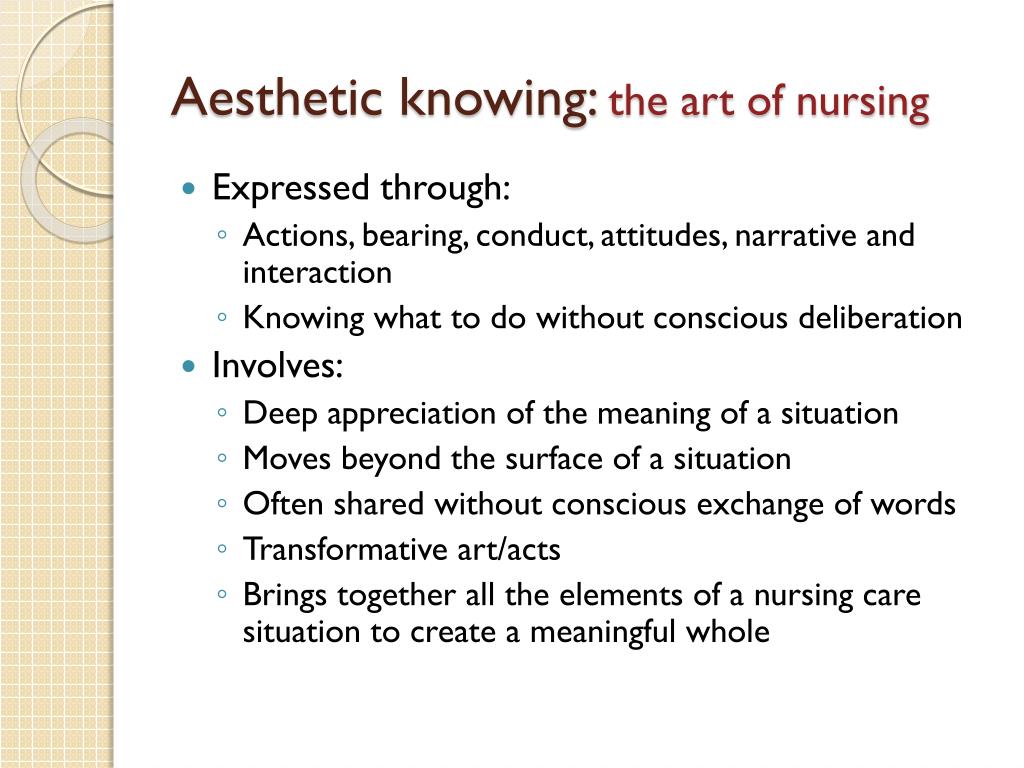

Aesthetic Knowing: The Art of Nursing

Aesthetic knowing, also known as the art of nursing, encompasses the nurse's intuitive understanding of the patient's subjective experience. It involves empathy, creativity, and the ability to connect with patients on a human level.

This type of knowing allows nurses to tailor their care to meet the unique needs of each individual, recognizing that a one-size-fits-all approach is often inadequate. Reading a patient's nonverbal cues, anticipating their needs before they are voiced, and creating a therapeutic environment all involve aesthetic knowing.

It's the understanding of the wholeness of the individual and what their needs are, separate from their diagnosis or treatment plan. This element can sometimes be the hardest to teach.

Personal Knowing: The Nurse's Self-Awareness

Personal knowing involves the nurse's understanding of themselves, their beliefs, biases, and values. This includes reflection on personal strengths, limitations, and the impact of their own experiences on their interactions with patients. It is critical for building authentic therapeutic relationships.

This pattern encourages self-reflection and can help nurses understand their own reactions to patients, thus avoiding unintended harm. For example, recognizing one's own biases toward certain patient populations is crucial for providing equitable care.

Journaling, mindfulness exercises, and supervision sessions can all help nurses develop personal knowing. It is through gaining clarity in who we are that we are able to fully know our patients and their needs.

Beyond the Original Four: Expanding the Framework

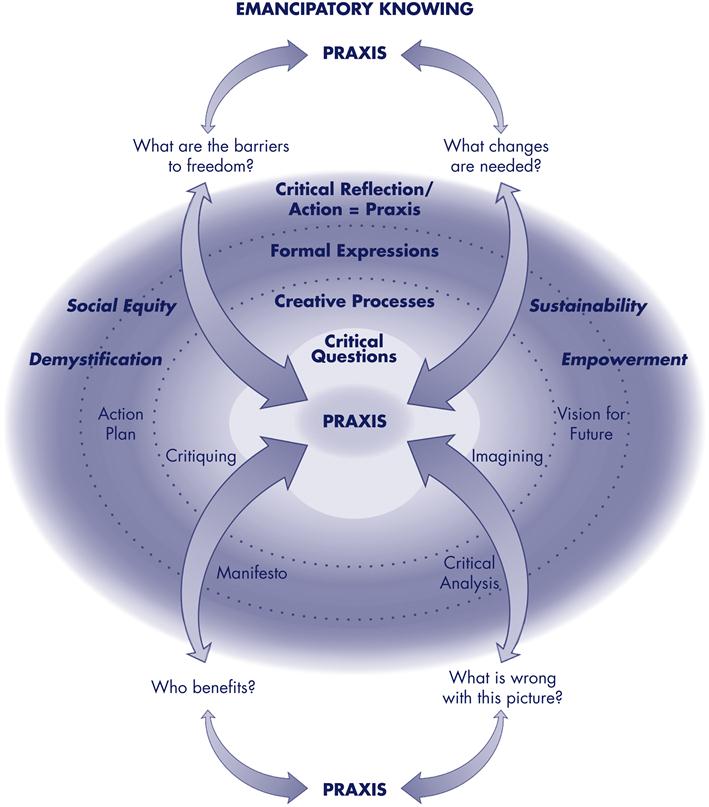

While Carper's four patterns remain foundational, scholars have proposed additional patterns to reflect the evolving complexities of nursing practice. One notable addition is Emancipatory Knowing.

Emancipatory Knowing: The knowledge of the social and political context of health and illness. It involves understanding how social inequalities, power imbalances, and systemic issues impact patients' health outcomes and advocating for change.

For example, a nurse using this pattern might advocate for improved access to healthcare in underserved communities or work to address health disparities related to race or socioeconomic status.

Application in Practice: An Integrated Approach

The patterns of knowing are not mutually exclusive; in practice, they are interwoven and interdependent. A skilled nurse integrates all these dimensions of knowledge to provide holistic, patient-centered care.

Consider a patient with chronic pain. The nurse draws upon empirical knowledge to understand the underlying pathophysiology and pharmacological interventions. They use ethical knowing to respect the patient's autonomy in making treatment decisions. The aesthetic knowing helps to appreciate the patient's subjective experience of pain and tailor interventions accordingly. Finally, the nurse uses personal knowing to reflect on their own attitudes toward pain management and ensure they are providing unbiased care.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite the widespread acceptance of the patterns of knowing, challenges remain in their application and assessment.

One challenge is the difficulty of measuring and evaluating aesthetic and personal knowing, which are more subjective and less easily quantified than empirical knowledge. Further research is needed to develop reliable and valid methods for assessing these dimensions of knowledge. In addition, a better means for teaching these principles needs to be researched and explored.

Furthermore, promoting the integration of all patterns of knowing in nursing education and practice requires a shift away from a purely biomedical model toward a more holistic, patient-centered approach. Institutions need to adapt to the growing importance of nurses and their diverse skills.

The future of nursing hinges on embracing and refining these fundamental patterns of knowing. By continuing to explore and expand our understanding of these essential knowledge domains, the nursing profession can ensure it is well-equipped to meet the ever-changing demands of healthcare.