How Do You Pay Taxes On Owners Draw

Small business owners, listen up: failing to properly account for taxes on owner's draws can trigger significant penalties. This article clarifies how owner's draws are taxed, and how to avoid costly mistakes.

Understanding the tax implications of an owner's draw is critical for business owners. It's not a salary, but rather a transfer of business profits to the owner, and Uncle Sam wants his cut.

Understanding Owner's Draws

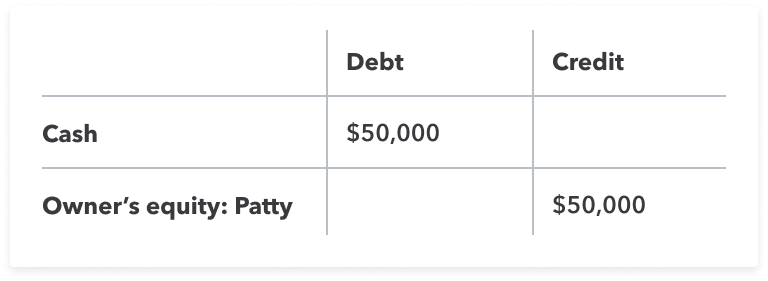

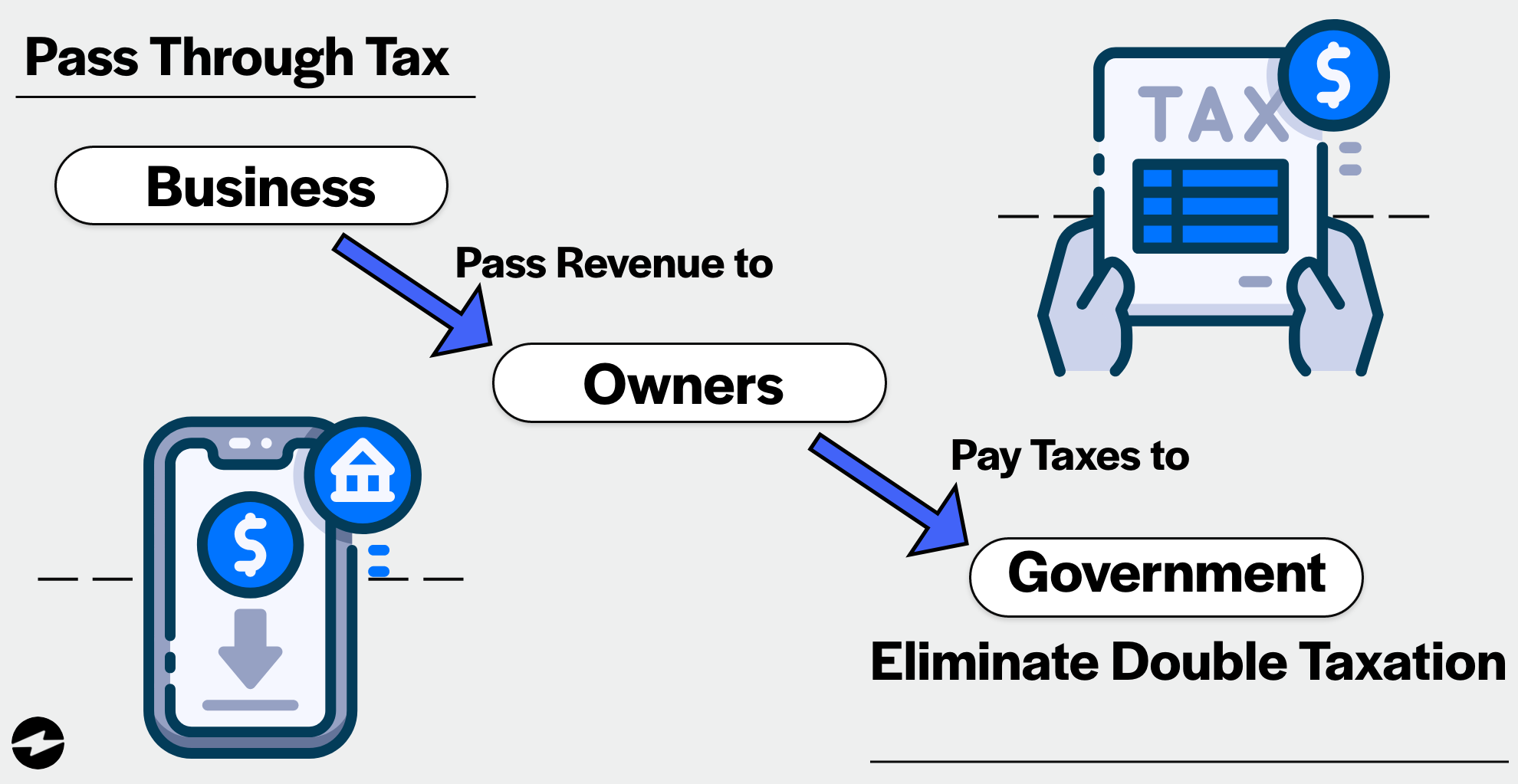

An owner's draw is a distribution of profits from a business to its owner(s). This is common in pass-through entities like sole proprietorships, partnerships, and S corporations.

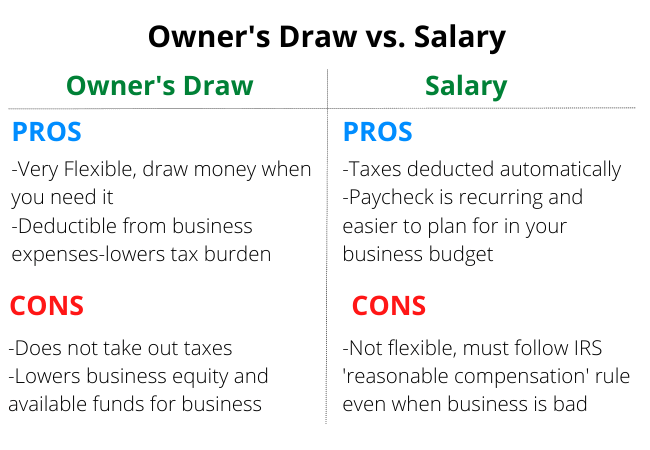

Unlike a salary, it's not subject to payroll taxes (Social Security and Medicare) at the time of the draw. But it's definitely not tax-free money.

Sole Proprietorships and Partnerships

For sole proprietors and partners, the business income passes through to the owner's individual tax return. This is reported on Schedule C (Form 1040) for sole proprietorships and Schedule K-1 (Form 1065) for partnerships.

The net profit from the business is subject to both income tax and self-employment tax. Self-employment tax covers Social Security and Medicare taxes, normally split between employers and employees.

The IRS allows you to deduct one-half of your self-employment tax from your gross income. This lowers your adjusted gross income (AGI), potentially reducing your overall tax liability.

S Corporations

S corporations introduce a slight twist. Owners who actively work in the business are considered employees.

They must pay themselves a "reasonable salary" subject to payroll taxes. Any additional withdrawals beyond this reasonable salary are treated as owner's draws.

These draws are not subject to payroll taxes, but they are still subject to income tax. The profit portion passes through to the owner's individual tax return via Schedule K-1 (Form 1065-B).

Estimated Taxes: The Key to Avoiding Penalties

Because taxes aren't withheld from owner's draws, you're responsible for paying estimated taxes throughout the year. These are generally paid quarterly.

Estimated taxes cover both income tax and, where applicable, self-employment tax. Use Form 1040-ES to calculate and pay your estimated taxes.

The IRS generally requires you to pay at least 90% of your current year's tax liability, or 100% of your previous year's tax liability (110% if your AGI exceeded $150,000). Failing to do so can result in penalties.

Calculating Estimated Taxes

Accurately predicting your business income is crucial. Review your previous year's tax return as a starting point, and adjust for any anticipated changes in revenue or expenses.

Several online tools and calculators can help you estimate your tax liability. Consider consulting with a tax professional for personalized guidance.

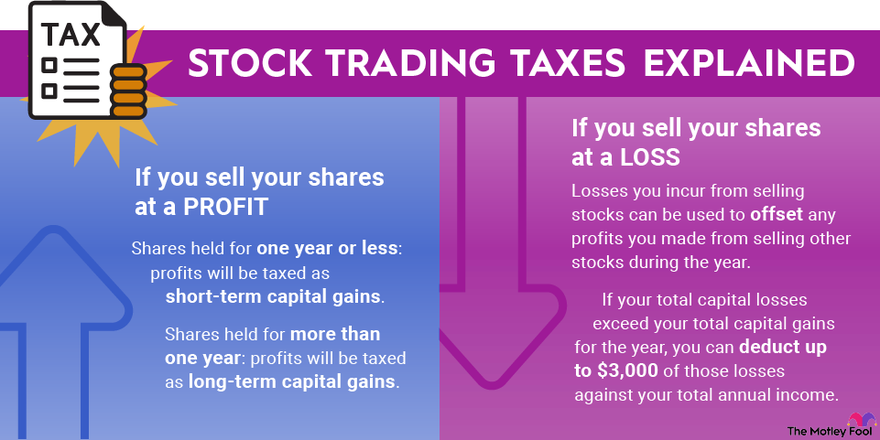

Remember to factor in any other income you may have, such as wages from a side job or investment income, when calculating your estimated taxes.

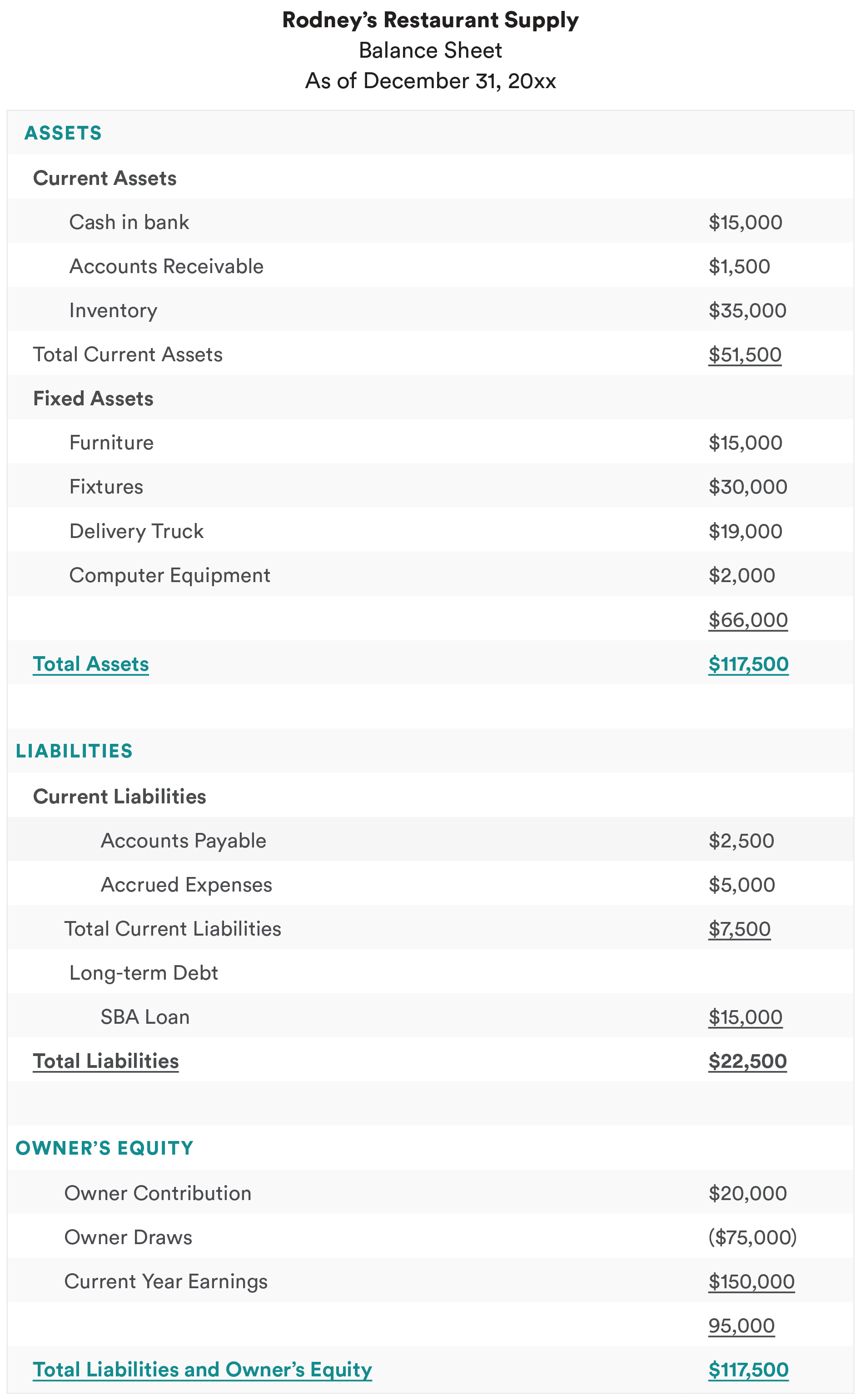

Record Keeping: Your Shield Against Scrutiny

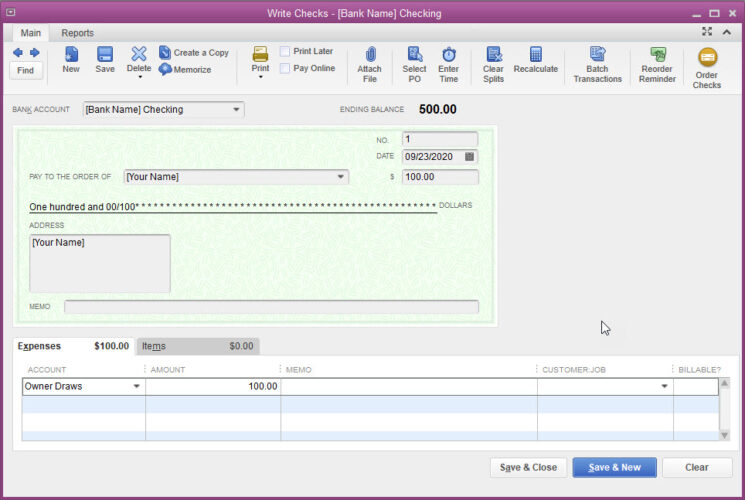

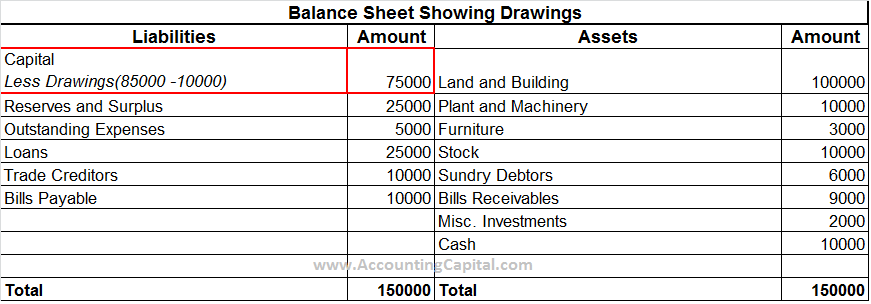

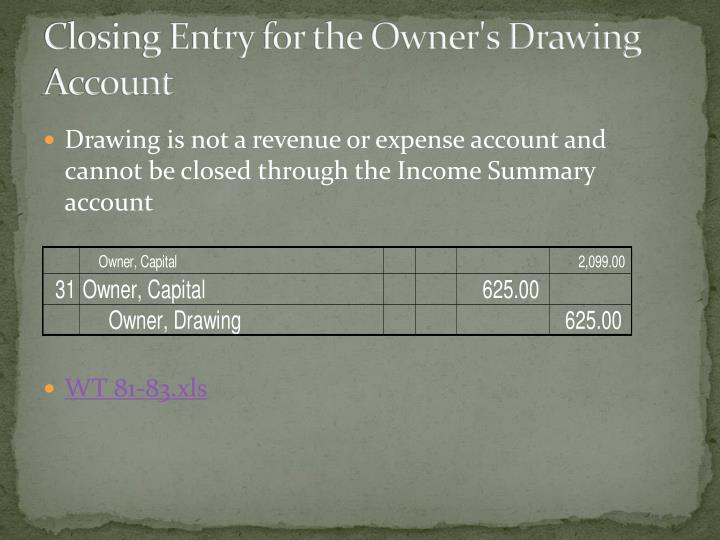

Maintain meticulous records of all income and expenses. This will help you accurately calculate your tax liability and support your filings in case of an audit.

Keep track of all owner's draws taken throughout the year. Document the dates and amounts of each withdrawal.

Use accounting software or a spreadsheet to organize your financial information. Consider using a professional like QuickBooks or Xero to simplify the process.

What to Do Next

Review your current tax strategy for owner's draws. Are you accurately calculating and paying estimated taxes?

Consult with a qualified tax advisor or CPA. They can provide personalized guidance based on your specific business structure and financial situation.

Don't wait until tax season to address this issue. Proactive tax planning is essential for avoiding surprises and minimizing your tax burden. Ignorance is not bliss, it's a penalty.