The Components Of The 4-term Contingency Include

Imagine a classroom buzzing with activity, not chaotic, but purposeful. A child, eyes wide with excitement, correctly answers a question, and their teacher beams, immediately offering a high-five and a cheerful "Fantastic!". The child's smile widens, a clear sign that something powerful is at play: the principles of the four-term contingency are shaping their learning journey.

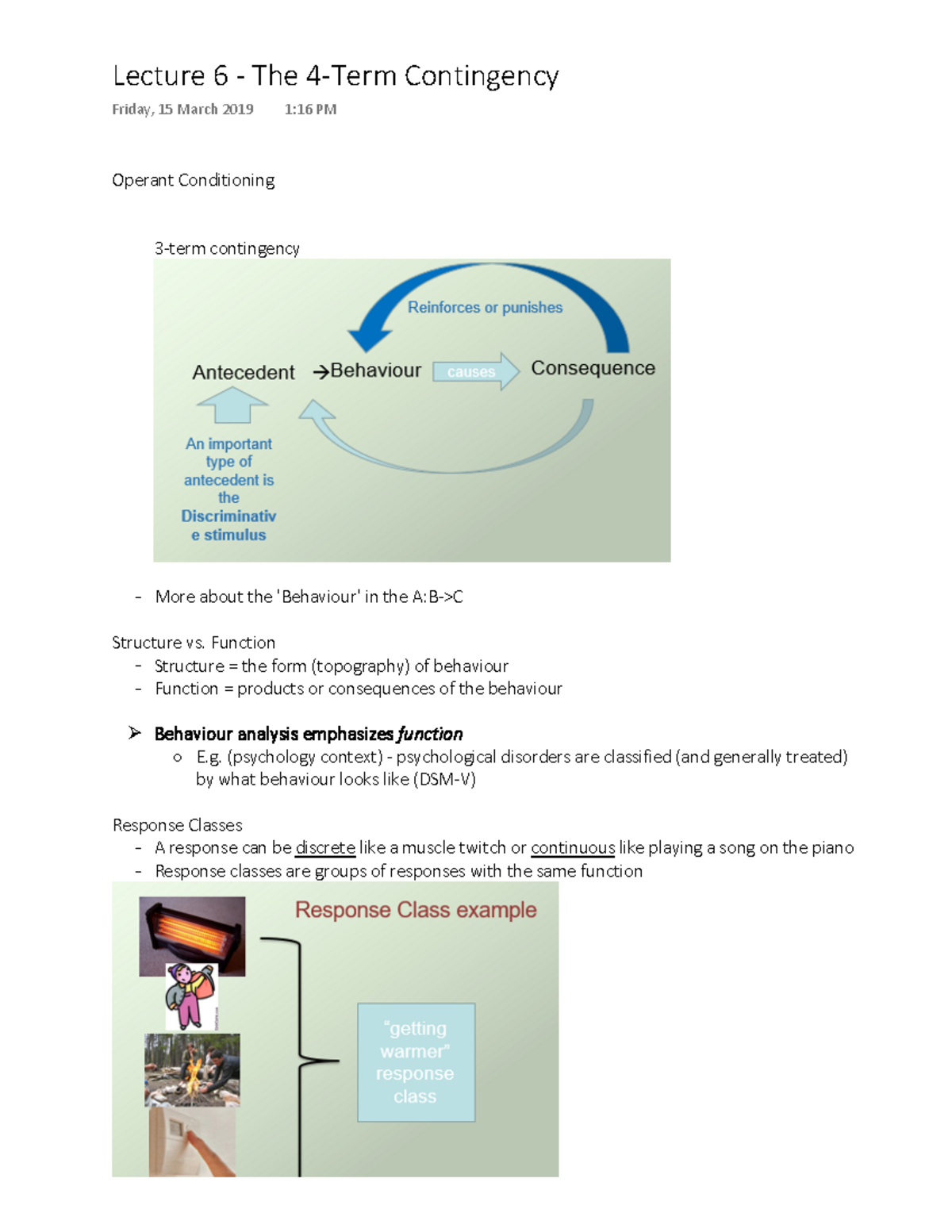

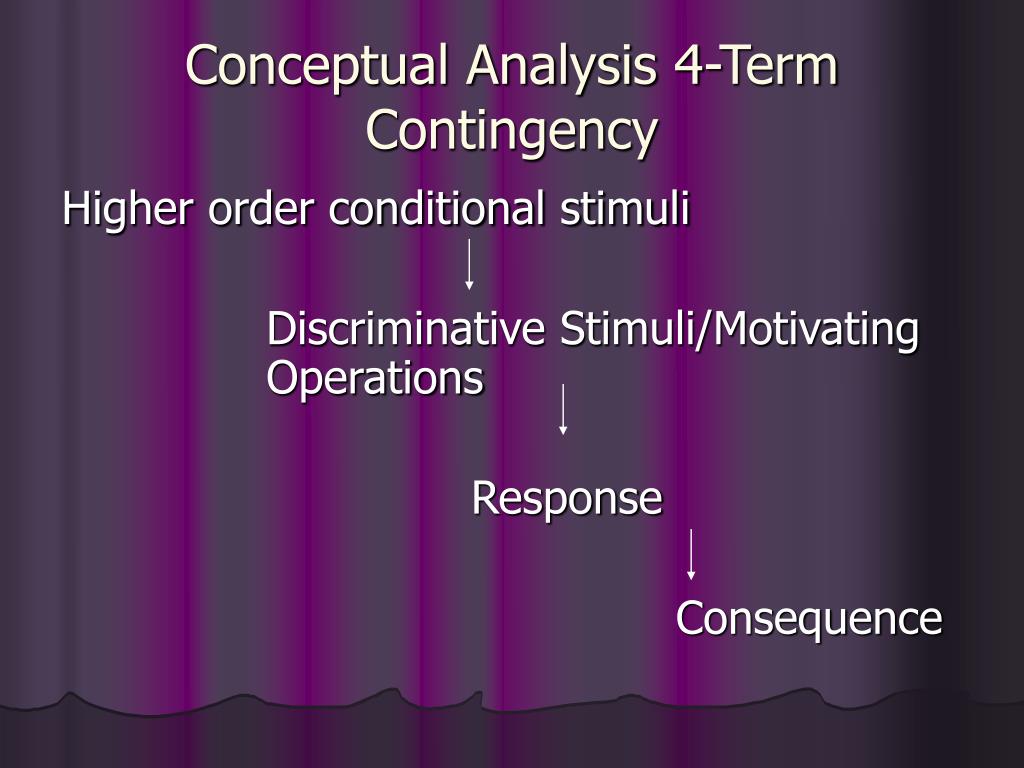

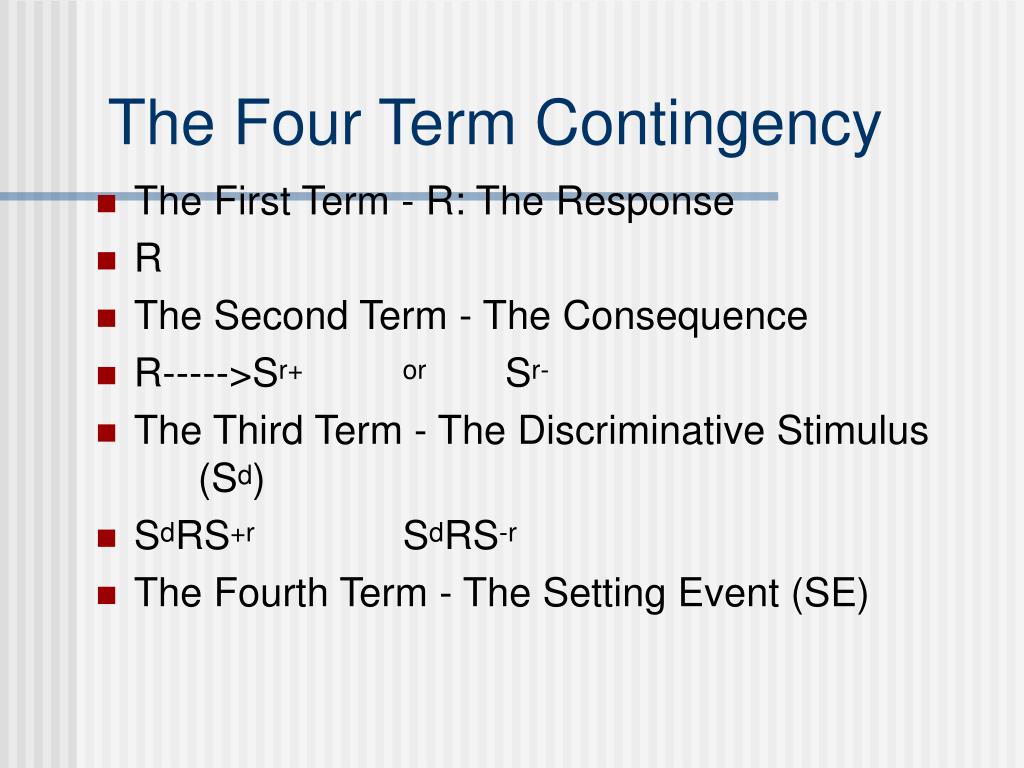

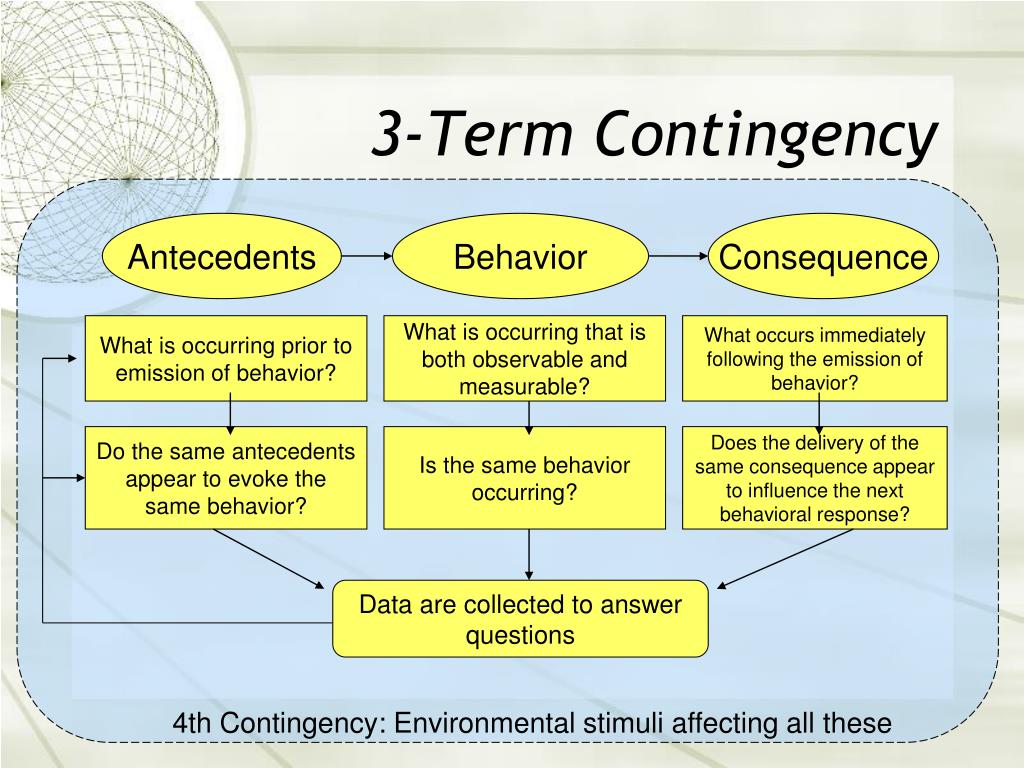

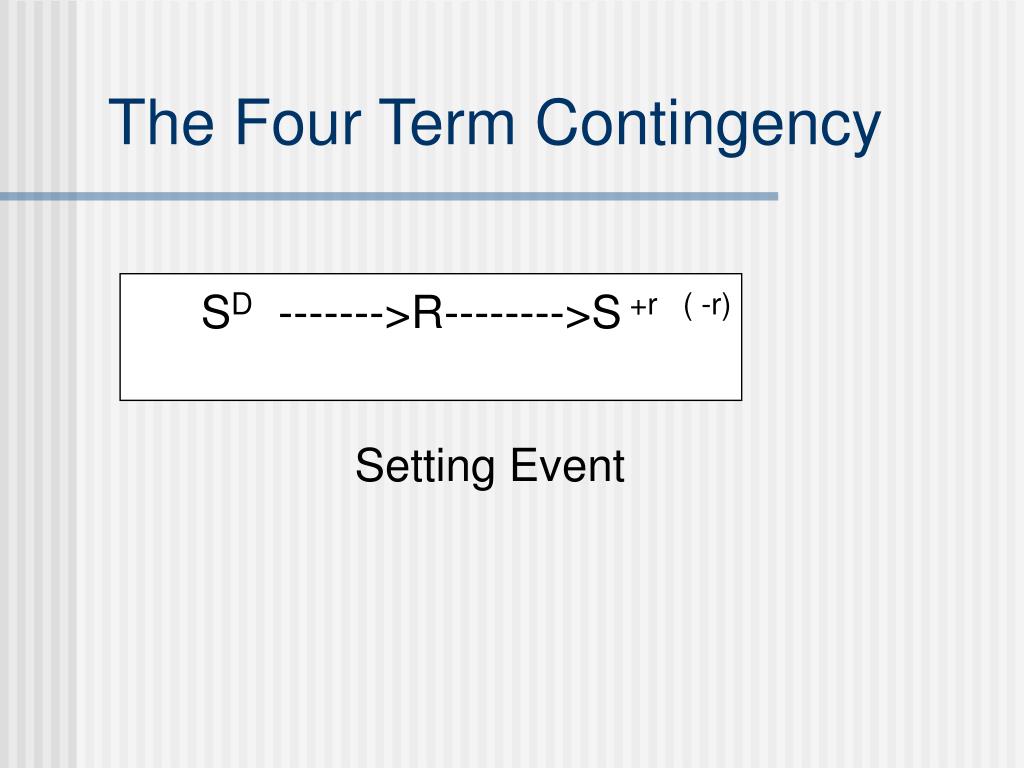

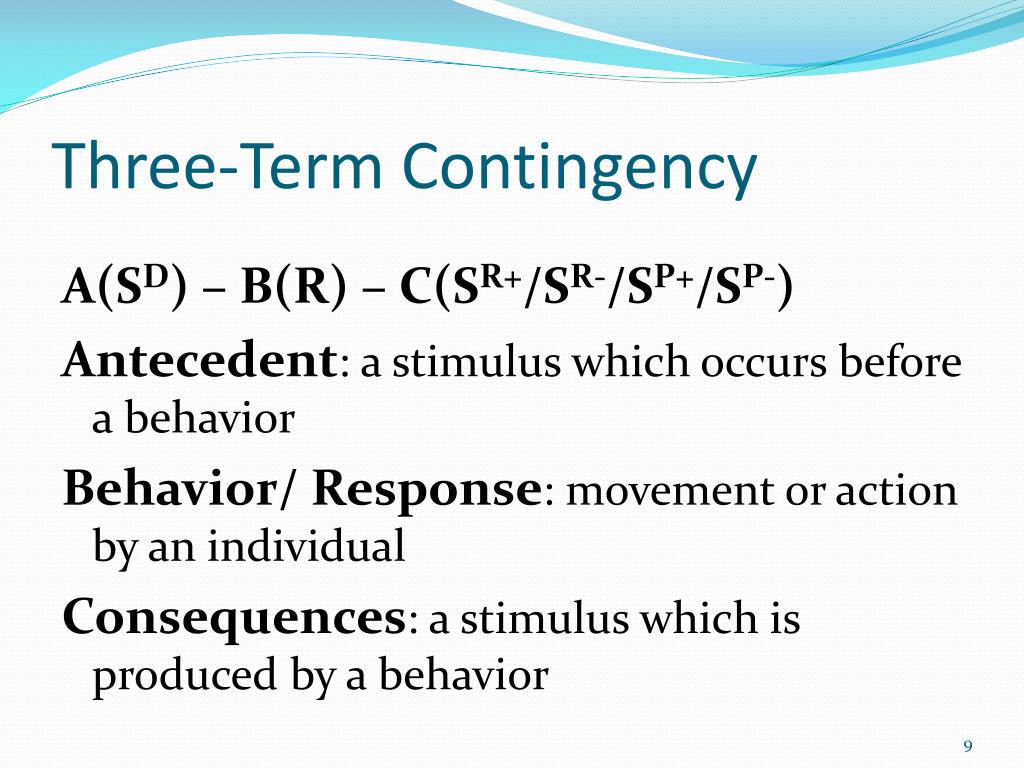

At its heart, the four-term contingency is a fundamental concept in behavior analysis. It explains how behaviors are learned and maintained by carefully considering the events that precede and follow them. Understanding its components – motivating operations, antecedent stimuli, behavior, and consequences – is critical for anyone interested in fostering positive change, whether in education, therapy, or even everyday life.

Unpacking the Four Terms: A Closer Look

The four-term contingency, sometimes called the "ABC model" plus a motivating operation, provides a comprehensive framework for understanding behavior. It allows us to analyze why someone does what they do, offering insights beyond simple observation.

1. Motivating Operations (MO)

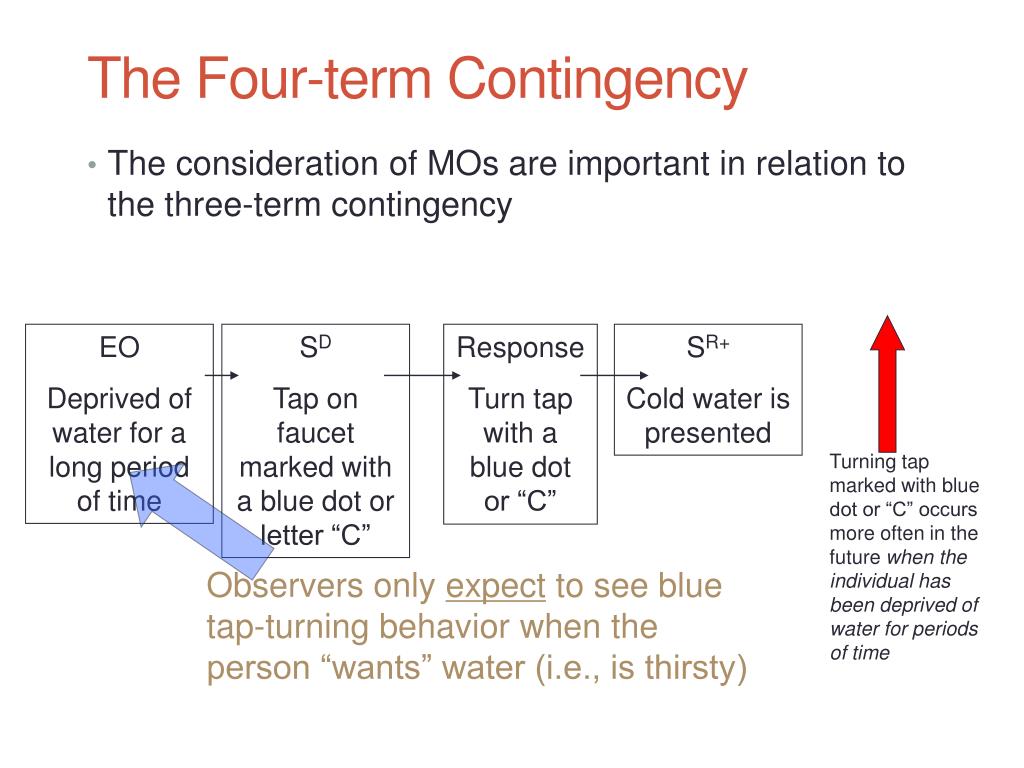

Before any behavior can occur, certain internal conditions often influence whether someone will act. These internal events are called motivating operations (MOs). They alter the value of a reinforcer or punisher, thereby influencing the likelihood of a behavior.

There are two types of MOs: Establishing Operations (EOs) and Abolishing Operations (AOs). EOs increase the effectiveness of a reinforcer, while AOs decrease it. For example, food deprivation is an EO that makes food more reinforcing, while satiation is an AO that makes food less reinforcing.

Imagine you haven't eaten all day. The mere sight of a restaurant (an antecedent stimulus, which we will discuss next) is much more likely to motivate you to go inside and order food (the behavior) than if you had just finished a large meal. This hunger state, a powerful establishing operation, is part of the contingency.

2. Antecedent Stimuli

Antecedents are the events, conditions, or stimuli that occur *before* a behavior. They set the stage for a particular response. These can be instructions, environmental cues, or even internal thoughts.

A red traffic light is a classic example. It’s an antecedent stimulus that signals drivers to stop their cars. Similarly, a teacher asking a question is an antecedent that prompts a student to provide an answer.

Consider a child who sees a cookie jar (the antecedent). The presence of the cookie jar alone doesn't guarantee the child will reach for a cookie. However, if the child is also hungry (influenced by a motivating operation), the cookie jar becomes a more powerful trigger for the behavior of taking a cookie.

3. Behavior

This is the action or response that a person exhibits. It must be observable and measurable. "Thinking" is not considered behavior in this context unless it is demonstrated through verbal or physical action.

Examples of behavior include speaking, walking, writing, or even a physical gesture like smiling or frowning. Defining the behavior clearly is crucial for effective analysis.

In our cookie jar example, the behavior is the child reaching for the cookie, opening the jar, and taking one out. This specific action is what we are trying to understand and influence within the contingency.

4. Consequences

Consequences are the events that follow a behavior. They determine whether the behavior is more or less likely to occur in the future. Consequences can be positive (reinforcement) or negative (punishment).

Reinforcement increases the likelihood of a behavior. Positive reinforcement involves adding something desirable (like praise or a treat), while negative reinforcement involves removing something aversive (like a chore). Punishment decreases the likelihood of a behavior. Positive punishment involves adding something aversive (like a scolding), while negative punishment involves removing something desirable (like screen time).

If the child takes a cookie and enjoys the sweet taste (positive reinforcement), they are more likely to repeat that behavior in the future when faced with the same antecedent (the cookie jar) and motivating operation (hunger). Conversely, if the parent scolds the child for taking a cookie without permission (positive punishment), the child may be less likely to repeat that behavior.

The Significance of Understanding the Four-Term Contingency

Understanding the four-term contingency provides a powerful lens for analyzing and modifying behavior. It moves beyond simplistic cause-and-effect thinking, offering a nuanced understanding of the factors that influence our actions.

In education, teachers can use this framework to create classroom environments that promote desired behaviors. By manipulating antecedents, providing effective reinforcement, and minimizing punishment, they can foster a positive learning environment. For example, posting clear instructions (antecedent), offering praise for completed work (consequence), and ensuring that students are motivated to learn (motivating operation) can dramatically impact student performance.

In therapy, behavior analysts use the four-term contingency to help individuals overcome challenges such as anxiety, phobias, and addiction. By identifying the antecedents and consequences associated with problem behaviors, therapists can develop interventions to modify them. For instance, helping someone identify triggers for their anxiety (antecedents) and develop coping mechanisms (behavior) that are reinforced by reduced anxiety (consequence) can lead to lasting change.

Even in our personal lives, understanding the four-term contingency can be beneficial. By becoming more aware of the factors that influence our own behavior, we can make more conscious choices. We can restructure our environment to promote healthy habits and reduce unwanted ones.

Putting it All Together: An Example

Let's illustrate the four-term contingency with a simple example: A student is studying for a test.

Motivating Operation: The student is concerned about getting a good grade and avoiding the negative consequences of a bad one (establishing operation). The desire to do well in school increases the value of studying.

Antecedent: The student sees a textbook (antecedent stimulus) related to the upcoming test. This visual cue signals the need to study.

Behavior: The student opens the textbook and begins reading and taking notes. This is the observable action they are taking.

Consequence: After studying for an hour, the student feels more confident about the material (positive reinforcement) and less anxious about the test (negative reinforcement). This feeling of competence increases the likelihood that the student will continue to study in the future.

If the student, however, feels overwhelmed and frustrated while studying (negative consequence), they may be less likely to engage in that behavior again in the future.

Looking Ahead: The Enduring Power of Behavior Analysis

The four-term contingency, while seemingly simple, offers a profound understanding of human behavior. It reminds us that our actions are not random but are influenced by a complex interplay of factors.

As we become more aware of these factors, we can harness the power of behavior analysis to create positive change in ourselves and in the world around us. From classrooms to clinics, from workplaces to homes, the principles of the four-term contingency offer a roadmap for understanding, influencing, and ultimately, improving behavior.

By understanding and applying the principles of the four-term contingency, we can move towards a world where behaviors are shaped by intentional design, promoting growth, learning, and well-being for all.

.jpg)