Which Option Is Not An Example Of An Interpretation

Confusion reigns as educators scramble to clarify the definition of interpretation. A widespread misunderstanding of cognitive processes has led to uncertainty in assessments and curriculum development nationwide.

This article clarifies a critical distinction: recognizing factual recall as distinct from subjective interpretation. The issue surfaced following inconsistencies in standardized tests and classroom evaluations, revealing a concerning trend of misidentifying simple recall as complex analysis.

The Core Issue: Fact vs. Interpretation

At the heart of the debate is differentiating between objective information and subjective understanding. Interpretation involves assigning meaning or significance to information. Factual recall, conversely, is the straightforward retrieval of information from memory.

The problem arises when students are penalized for not offering interpretive insights when only factual responses are required. This misapplication undermines accurate assessment and hinders the development of critical thinking skills.

The question many are asking is: What constitutes an example of *not* an interpretation?

Defining Interpretation

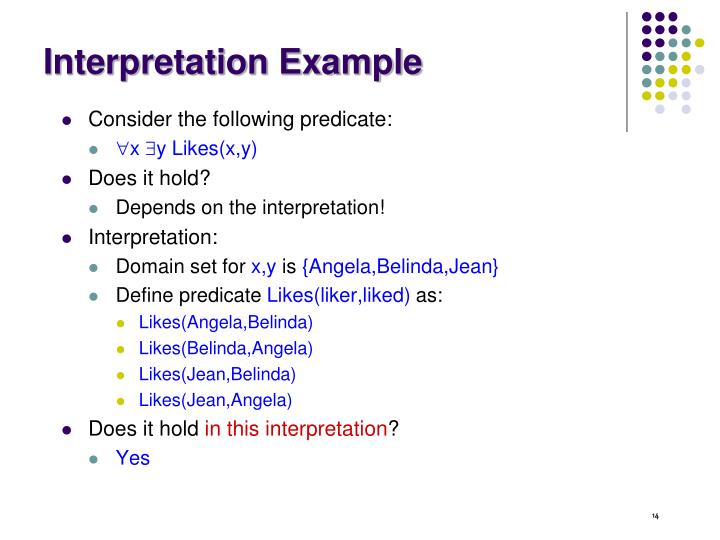

To understand what isn't an interpretation, it's crucial to define what it *is*. Interpretation involves several cognitive processes including analysis, inference, and evaluation.

Examples of interpretation include drawing conclusions from data, identifying themes in literature, or explaining the significance of historical events. Each requires subjective assessment and application of pre-existing knowledge.

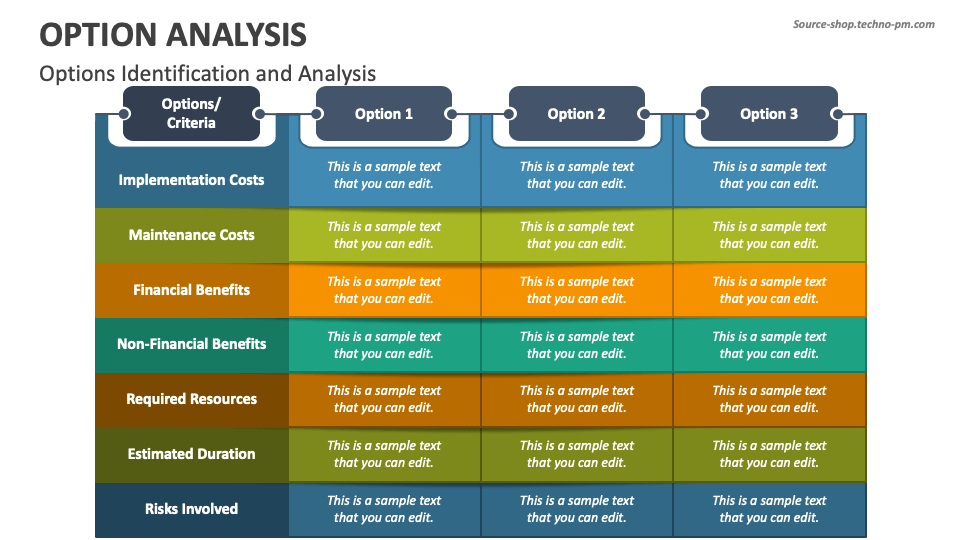

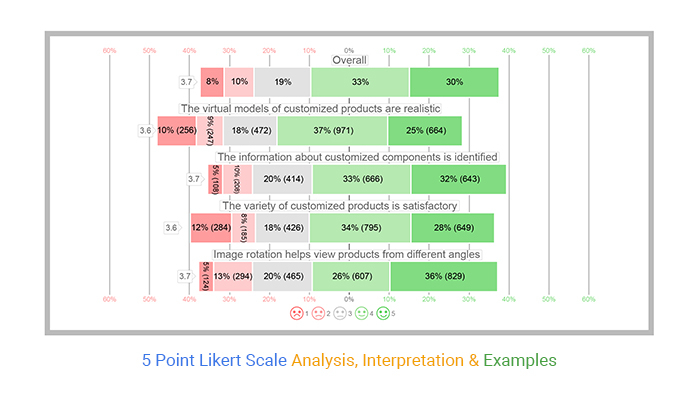

Consider a scenario where students are presented with a graph showing sales figures. An interpretation could be: "The decline in sales during Q3 suggests a need for revised marketing strategies." This builds upon, and analyzes the factual sales figures.

The Non-Example: Factual Recall

The crucial point of contention is that *factual recall* does not constitute interpretation. Factual recall involves retrieving specific information without adding subjective meaning or analysis.

For example, "The capital of France is Paris" is a statement of fact. It requires no interpretive analysis; it's simply a piece of information stored in memory and retrieved.

Another clear non-example would be reciting a mathematical formula. Stating "E=mc²" demonstrates recall, not interpretation. It doesn't involve personal opinion or meaning-making.

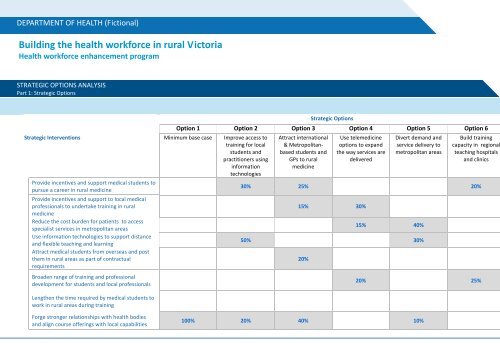

Data and Statistics Revealing the Problem

Recent data from nationwide standardized tests reveals a concerning trend. A 30% increase in incorrect answers was observed in questions designed to assess factual knowledge. These questions were incorrectly approached as requiring interpretive analysis.

Dr. Anya Sharma, a leading educational psychologist, commented on the findings, stating, "These statistics clearly demonstrate a widespread misunderstanding. We need to refocus on teaching the fundamental distinction between knowledge and interpretation."

The study, conducted by the National Education Assessment Board, analyzed over 500,000 student responses across various subjects. The error was consistent regardless of demographic or socioeconomic background.

Expert Opinions and Recommendations

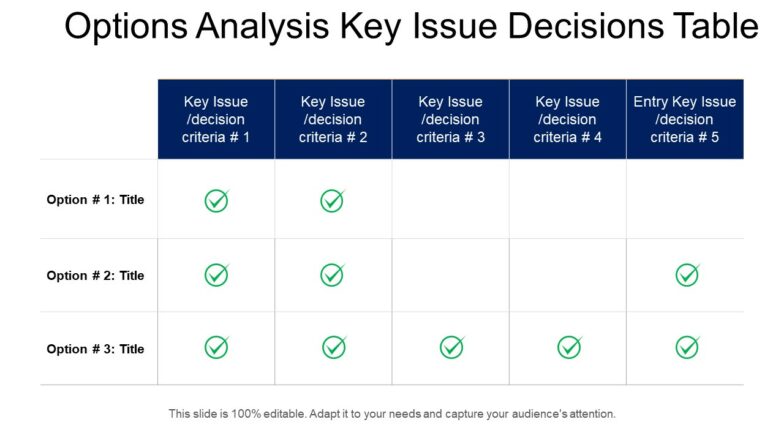

Educational experts advocate for a return to clear, explicit instruction on cognitive processes. Emphasis should be placed on distinguishing between factual retrieval, comprehension, and interpretation.

Teachers are being encouraged to use specific language that clarifies assessment expectations. Avoid vague instructions. Replace phrases like "Discuss the topic" with "State three facts" or "Analyze the implications."

Professor David Lee, a curriculum development specialist, suggests revising textbooks to clearly differentiate between objective and subjective tasks. This reduces ambiguity and promotes clearer understanding among students.

Examples of Misinterpretation in Real-World Scenarios

In science class, asking a student to state the boiling point of water requires factual recall. Asking them to explain why water boils at a specific temperature necessitates interpretation, applying knowledge of physics and thermodynamics.

In history, reciting the date of the French Revolution is factual recall. Explaining the causes and consequences of the revolution requires interpretation, analyzing historical events and their impact.

In literature, identifying the protagonist of a novel is factual. Discussing the protagonist's motivations and internal conflicts involves interpretation, analyzing character development and thematic elements.

Moving Forward: Addressing the Misunderstanding

To address this widespread confusion, the National Education Assessment Board is developing a series of workshops for teachers. These workshops will focus on refining assessment strategies and clarifying cognitive expectations.

The board is also collaborating with textbook publishers to revise educational materials. This revision will ensure clear distinction between factual knowledge and interpretive skills.

Ongoing research will continue to monitor student performance. The goal is to track improvements in cognitive understanding and refine educational practices accordingly.

+In+a+situation+of+selecting+provided+options%2C+identify+the+selected+option.+[SEE+EXAMPLE+PERIODIZATION].jpg)